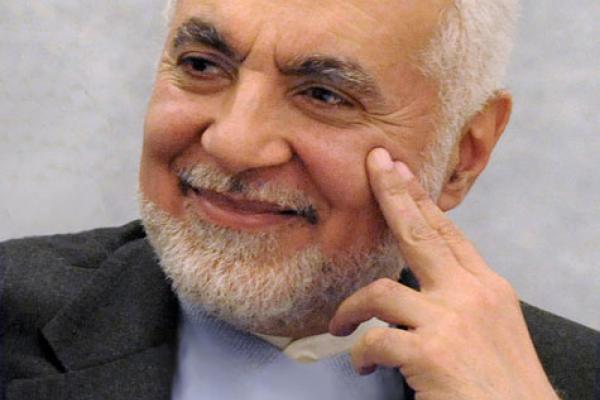

Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf has spent most of his adult life trying to build interfaith and international bridges. But to many Americans, he is the public face of the so-called "Ground Zero mosque," one of the most controversial religious projects in recent U.S. history.

Rauf reflects on that turmoil in his new book, Moving the Mountain: Beyond Ground Zero to a New Vision of Islam in America. But as the book's subtitle suggests, the longtime imam spends most of his time facing forward — toward the development of a distinctly American brand of Islam. He spoke recently with Religion News Service. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Why did you write this book?

A: I wrote this book because the American public saw me and heard me, but really didn’t get to know me very well, or to understand what my work was all about. This book is my calling card to the American public.

Read the Full Article