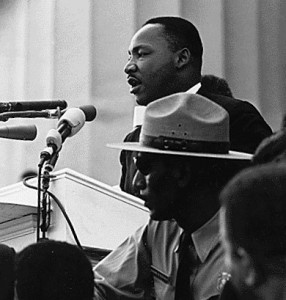

At the dedication ceremony for the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, at least two speakers -- the Rev. Bernice King, Martin Luther King's daughter, and the Rev. Jesse Jackson, one of King's lieutenants -- reminded us that at the end of King's life he was planning the Poor People's March

At the dedication ceremony for the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, at least two speakers -- the Rev. Bernice King, Martin Luther King's daughter, and the Rev. Jesse Jackson, one of King's lieutenants -- reminded us that at the end of King's life he was planning the Poor People's March

The Poor People's March is an ancestor to the current Occupy Wall Street movement that we see breaking out across the globe today. The idea was to bring poor people from across the color line -- white, black, brown, red, yellow -- to Washington to call attention to the importance of economic justice. King understood that economic justice -- distributive justice -- was not a matter of race in the United States.

It was true then, and it is true now that African Americans and Latino/as suffer disproportionately from income inequality. But it is important to remember that people of all colors suffer from the corrosive effects of income inequality. Some of the poorest communities in the country are European American. The poorest states in the United States with some of the worse educational and health care outcomes are states in the former confederacy.

Income inequality has increased since 1968. So the question that insists upon being answer is this: Why has income inequality worsened between 1968 and today?

Read the Full Article