Biting and unbelieving comedian Bill Hicks challenged Christians about wearing crosses around our necks. He chided us that when Jesus comes back, the last thing he would want to see is another cross. Not unlike Hicks, liberal theologians get squeamish about the saving power of the cross and distance themselves from it with critiques that attack academic euphemisms like blood atonement.

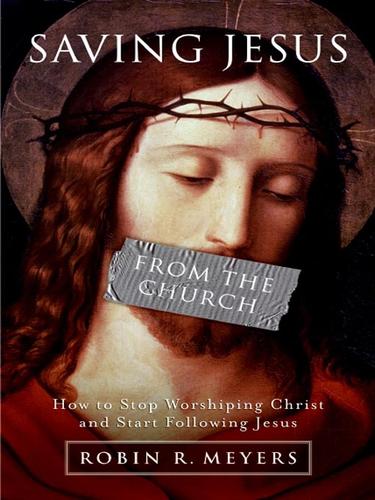

My friend, colleague, and our “religion and culture” book-discussion leader assigned our Sunday school class homework this week: Consider and contemplate our understanding of and relationship with the cross. And do this in the context of a compelling and challenging chapter called “The Cross as Futility, Not Forgiveness” in an excellent and provocative book we’re reading by Robin Meyers called Saving Jesus From The Church: How to Stop Worshiping Christ and Start Following Jesus. This post serves as part of my response to that homework.

Crosses as powerful symbols predate Christianity and are not the singular insignia of our faith. Some Christians prefer the fish to the cross as an identity marker for Jesus followers. I confess I simultaneously love the empty cross and accept brutality of the bloody crucifix. As contradictory and ubiquitous its grip on our consciousness, we cling to it in comfort. As theologically problematic as we might render its salvific power, we sing of “the rugged cross” and need “nothing but the blood.”

From my enormous sympathies for Meyer’s intentions and investigations, I’m ultimately left lingering with discontent at his conclusions. I easily devoured Saving Jesus, and alongside my mixed reactions to the text, our class discussions have helped me to wrestle with not just my responses to the book in particular but to clarify my faith and theology more generally.

As an activist-poet-professor who’s taken up residence in the emerging church as a lay preacher-theologian-seminarian, I feel the most solidarity with Christians concerned about issues of inclusion and creation care and peace and civil rights. Raised by my movement veteran parents in a household that’s had a Sojourners subscription for three decades, my faith journey is inseparable from a commitment to radical social action. In this regard, I presume Myers and I are fellow-travelers.

So it’s with some trepidation that I tread back towards what feels like a more conservative position theologically than his, away from what I perceive as his partisan progressive Jesus-ism, admittedly purported in his book as an overdue antidote for the out-of-control errors of an overtly-Americanized fundamentalist Christianity.

In the chapter on the cross, Meyers bypasses blood atonement, replacing Jesus dying for our sins with Jesus dying because of our sins. He rejects the worst aspects of an atoning theology this way: “Instead of a verdict on the ultimate futility of violence, it actually commends it and sends a chilling message to the human species: violence saves.”

In the chapter on the cross, Meyers bypasses blood atonement, replacing Jesus dying for our sins with Jesus dying because of our sins. He rejects the worst aspects of an atoning theology this way: “Instead of a verdict on the ultimate futility of violence, it actually commends it and sends a chilling message to the human species: violence saves.”

Many of us can agree with Meyers that we need to be careful in understanding where the theology of substitutionary blood atonement can take us and preach against the religious justification for the prevalence of gratuitous violence—real and imagined—in politics, foreign policy, police work, and popular culture.

But what about the cross—not just in our theology but in our liturgy, not just in our politics but in our personal lives—has this symbol exhausted its purpose or its iconic pull? Does it still maintain a saving and prophetic role?

Crosses in the cosmic sense compel us to contemplate the simultaneous transcendence and immanence of God, the unavoidable intersection of the vertical and horizontal axes of life, the incarnate mystery of God’s distance and closeness, a God who is both our companion and our creator. Add the circle to the Celtic cross, and we have a symbol with interspiritual implications, a Christianity engaged and embedded with an essential lunar or solar or terrestrial unity linked to a perennial naturalism and its pagan predecessors.

But crosses in their contextual and corporal sense cause extreme discomfort. That one as beautiful as Christ requires a cross so curdles our consciousness, so confronts us with the violence embedded in our confession of a gentle and loving God who was tortured and murdered by the state that we’ve made it curt and cute with sentimentality and signification. Some prefer the cross as souvenir and sign because to embrace the full potency of its symbolism could make the entire prospect of our religion unpalatable and disgusting.

That’s what my atheist sister sees and my fundamentalist brother still promotes as a reading of this narrative: a violent vengeful domineering God who requires the murder of his beloved son to save the rest of us wretched cretins from an even greater wrath. It’s no wonder liberal theologians seek an alternative narrative to this. At its worst, even this Jesus is a rebel son whose teachings are irrelevant and who doesn’t reveal the nature of his father God but rather flees God in the garden and ultimately submits to be tortured alive by God. And yet erasing atonement might not be the only alternative to this.

But doesn’t Christ’s sacrifice end all sacrifice, redeem all sin? Of course we claim “it is accomplished,” but we don’t act like it. In the years since Jesus walked among us in the flesh, we never really acted like it. Sin and evil are still loose in the world.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, we sell these symbols in a manner that would prompt Meyers to bemoan the “perfumed rack” where a “symbol of evil is now worn as personal adornment” from “belly-button rings” to “expensive bling.” In the 20th and 21st centuries, we’ve seen crosses and crucifixions proliferate in bomb and bullet, looting and lynching, disease and destruction.

But finally my faith forces me back to Golgotha and its harrowing holy horror. For the Christian to deny cross and crucifixion would be for the soldier to deny artillery and enemies, for the addict to deny drug and drink, for the lover to deny longing and loneliness. Brennan Manning boldly charges, “The day we cease proclaiming Jesus Christ nailed to the cross is the day we effectively part company with the gospel.”

There’s no comfortable workaround for the narrative sting: our nonviolent Godman died a violent death at the hands of an empire. Question as we might at the cold missteps of Nietzsche or anyone who speculates about the death of God, admittedly our worship and wonder must pass first through the death of God.

The holy meal that precedes this sacrifice to end all sacrifices seems no less sickening at the surface, and yet we relive it daily or weekly or monthly or cyclically. As disciples, we’re consumed and consuming in what makes outsiders uncomfortable, a meal made of our savior, a strange love feast it or rude cannibalistic rite the Eucharist still appears to be.

The cross as symbol fulfills an ultimate faith but at its face value forces us into the chamber of its antithesis, the annihilation of the great commandment of love and loyalty in a spectacle that sure looks like hatred and domination. The obvious futility of the cross cannot crush its overarching reality, its truth, its pain, plain and profane. We meet the soul force of Christ’s love on the cross in contrast to the chasm it crosses. The nonviolent way of the peacemaker savior breathes light into the shadows where violence still lurks.

The cross as symbol fulfills an ultimate faith but at its face value forces us into the chamber of its antithesis, the annihilation of the great commandment of love and loyalty in a spectacle that sure looks like hatred and domination. The obvious futility of the cross cannot crush its overarching reality, its truth, its pain, plain and profane. We meet the soul force of Christ’s love on the cross in contrast to the chasm it crosses. The nonviolent way of the peacemaker savior breathes light into the shadows where violence still lurks.

All the shame and blame of centuries of accumulated violence—that’s certainly Jesus dying because of our sins. But if Jesus didn’t die for our sins as well, it’s not because we were not collectively aching for such a cosmic rescue mission. Some folks who have lived genuinely decent lives generally free of serious sin question whether our human nature is as fundamentally flawed as Christian doctrine suggests.

For those people, it might be more helpful to reframe sin as a general state of estrangement and distance from our essential unity with God. For others who have consciously participated in evil, who have felt the demonic grip and wholeheartedly denied God’s love through selfish acts whether individual or collective, we have become sin and have begged in foxhole prayers in desperation for the one who would become sin for us. We have crosses to bear and thorns to wear. We have felt the nails, tasted the blood.

That Christ chose and even accepted crucifixion shows the paradoxical power of powerlessness as an alternative to the powerful structures of a world that worships power. But the wisdom of grace and nonviolent solidarity succeed in sacred terms because they also fail in a world that at times is anything but filled with grace and nonviolent solidarity.

The “pre-Easter Jesus” (to borrow Marcus Borg’s phrase) may or may not have been fully cognizant of his saving task for all time, but centuries of Christians have been convicted and converted by it. We accept a Jesus who accepted the world’s rejected ones and rejected values the world finds all too acceptable. We know Jesus’s nonviolence in the context of violence. We know grace in the context of sin—not just collective, social, and institutional sin, but individual, personal, and secret sin.

Ought we revise the core of Christianity to please the morality of a modern liberal sensibility? Or undo orthodoxy to appease those Americans revolted by burning crosses or the cross compared to the lynching tree? Or offended by contemporary crucifixions wrought with a bullet in Memphis or an airplane crashing into New York City?

The politically grotesque passion narrative possesses an undeniable drama and a personal magnetism that’s even more tragic, and the tragedy touches us at our inner core. Granted, we’ve all encountered a preacher in whose hands this story has been a tool of fear and foreboding, terror and control.

But how many more of us have had to meet Him in all our naked vulnerable humanity, when embracing Christ’s suffering has been a window to understanding and ultimately being freed from our own?

I know a conservative theology exists that takes up cross but not teaching, ignoring the humble practices that could inhabit all preaching. But a progressive critique of that twisted and authoritarian cross need not rob us of the salve that stains the palms of our paschal savior, our marvelous mediator and living liberator. At the feet of the cross we revel in the mystery and martyrdom, savoring His sacrifice without over-romanticizing the banality and brutality of its context or ours.

After Paul, we preach and teach Christ crucified. We follow Christ resurrected. Are we not a revolutionary Easter band still willing to walk the solidarity stations of a Good Friday plan? Such lonely soul sickness our savior saves us from with limitless love. Such restoration promised to the beauty of creation spoiled by the arrogance of civilization. Such liberation offered from the blindness of ism and schism, derision and delusion.

Shocking still, the scandal of that hill. A folly full, but we follow its will. A place exists past categories conservative or liberal, past distinctions of ideology or theology, past wars and rivalries, let’s meet our risen Lord there, touch those hands like Thomas, a meal there we will share.

Andrew William Smith is an English professor by day and DJ by night who works as the Faculty Head of Tree House living and learning village at Tennessee Tech. He’s an activist, poet, blogger, writer/editor at Interference.com, seminarian, unlikely Sunday school teacher, and aspiring preacher. Follow Andrew on Twitter @teacheronradio or on Unlikely Sunday School Teacher, where this post originated.

Image: Kildalton cross, Ireland. Image by Jaime Pharr /Shutterstock. Crucified hand photo by Kevin Carden /Shutterstock.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!