More than 40 years have passed since Sally Priesand was ordained as the first female rabbi in the U.S. Since then, more than 800 female rabbis — including 647 in the Reform movement — have graduated from several seminaries, including my daughter Eve.

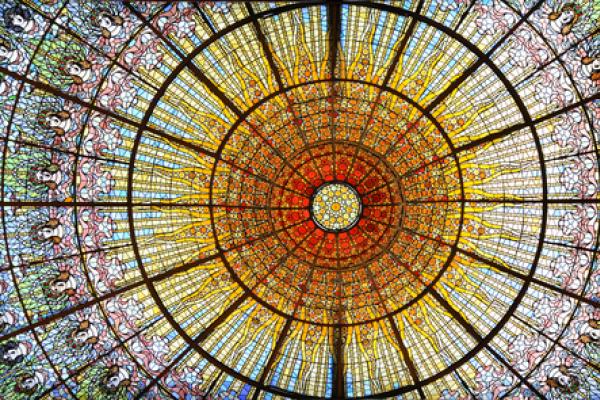

Even so, Jewish and Christian clergywomen still face visible and invisible obstacles in their careers. Call it the persistent stained-glass ceiling. Some barriers are major in nature; some minor.

A male rabbi, minister or priest might be praised for being “assertive” and “ambitious” as he climbs the slippery ladder of success in American religious life. But women who possess similar qualities are dubbed “brash” or “arrogant.” Male clergy can be “dynamic,” while women with the same qualities are often termed “strident.”

Good sermons delivered by men are “eloquent” or “expressive.” A woman delivering a well-crafted sermon is often dismissed as “talkative” or “shrill.” Males may have a “commanding presence,” while strong women clergy are “overbearing” and “pushy.”

For men, professional dress is easy. Christian pastors and priests can wear distinctive clerical garb and a rabbi’s “uniform” is a dark suit, dress shirt, tie and black shoes. But women are judged by the length of their skirts, the way they cross their legs (or not) during a service, their shoes, their jewelry or lack of it, their makeup and, of course, their hairstyles.

While Jewish and Christian female clergy have created and introduced new creative liturgical ceremonies for births, baby namings, bar/bat mitzvahs, weddings and other “happy” events in life, many women have problems when they officiate at funerals. It seems many people still feel more comfortable with a male figure officiating at such solemn and sad occasions. That is because many people still perceive women clergy as “cheery” and “chirpy” while men are “somber” and “serious.”

Male clergy may exhibit “empathy” for the grief-stricken, while women, who offer similar spiritual consolation, are dismissed as too “touchy-feely.” Clearly, a double standard is at work that reflects the prejudices, whims and caprices of the general society.

Women achieved voting rights in the U.S. in 1920, but nearly a century later women make up half of our population but only 20 percent of the U.S. Senate and less than a quarter of the House. Likewise, too many women are still assistant or associate clergy in congregations that are guided at the top by men. The number of women holding a “solo pulpit” remains a significant measure of how rigid the stained-glass ceiling remains.

Until recently, religious scholarship was an encrusted male monopoly. But as more and more women join seminary faculties, they have discovered and in some cases rediscovered the major importance of women throughout Jewish and Christian history. Such pioneering academic studies have gone far beyond the usual listing of women in the Bible; we now know more about the unknown and unappreciated women who strengthened both Judaism and Christianity.

Today, permanent changes are shaping American religious communities and their clergy. The signs are everywhere: More and more women are attending seminaries, and even Pope Francis has called for a greater role for women within the Catholic Church. While he has closed the door on ordaining female priests, a Catholic colleague reminded me: “A door is not a wall. It can always be opened.”

Even within the male-dominated Orthodox Jewish community, similar pressures are building. An independent rabbinical school in New York City recently created the title “mahrat,” a Hebrew term to describe female clergy in a tradition that does not ordain women rabbis. Several women have already earned that title and assumed groundbreaking roles within their community.

Hopefully, the days are long over when women were relegated to church and synagogue kitchens and volunteer roles within congregations. The day is coming when wide-eyed youngsters in numerous synagogues and churches will soon ask: “Can a man be a rabbi, minister or priest, too?”

Rabbi Rudin, the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser, is the author of the recently published “Cushing, Spellman, O’Connor: The Surprising Story of How Three American Cardinals Transformed Catholic-Jewish Relations.” Via RNS.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!