While he waits for the Brazilian faith healer to arrive, Paul Simon is supposed be meditating quietly with his eyes closed.

Instead, he’s peeking.

“I want to see what’s going on,” Simon said, recalling his visit to the Casa de Dom Inácio de Loyola in Abadiânia, Brazil, where, in the summer of 2014, he underwent a "spiritual operation" performed by João Teixeira de Faria — a medium and psychic healer known as João de Deus (or "John of God”).

Eventually, John of God enters the room where Simon and about a dozen other pilgrims, a few lying on gurneys, await with varying degrees of patience, anxiety, and faith.

“He speaks in Portuguese — I assume a prayer — and he leaves,” Simon said. “And then everyone gets up and leaves the room. And I say to my guide, ‘Well, when is the operation?’ And she says, ‘No, that was it. You had it.’ … I felt nothing.”

While in Brazil — a 10-day trip he took at the urging of his wife, the musician Edie Brickell, who had traveled to Abadiânia for her own "spiritual surgery" several months earlier — Simon began writing the song "Proof of Love,” a six-minute epic that is, arguably, the centerpiece of his masterful new album.

I trade my tears

To ask the Lord

For proof of love

If only for the explanation

That tells me what my dreams are made of…

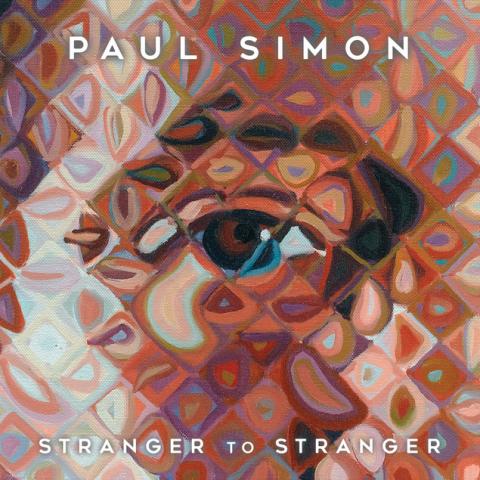

Stranger to Stranger, his 12th solo album, is rich with the singularly vivid storytelling that long ago earned Simon his place in the American music pantheon. He invites listeners on a sonic journey with more than a whiff of spiritual exploration — a familiar theme for careful listeners to his half-century of music-making.

A Half-Century-Long Musical Conversation

Expressed in his music, Simon’s spirituality is experiential, what the German theologian Rudolf Otto might have called “numinous” — it expresses a connection to the “wholly Other” that is deeply personal and awesome (in the literal meaning of that word). In his The Varieties of Religious Experience, the philosopher William James might have described it as “mystical,” as in “mystical states seem to those who experience them to be also states of knowledge … illuminations, revelations, full of significance and importance, all inarticulate though they remain.”

It also is in a sense ineffable, a conversation about transcendent experiences that unfolds as much in the sound as it does in actual words that Simon sings.

Since the 1960s, Simon’s musical dialogue with his audience has been an adventure: through the mean streets of pre-Bloomberg New York City, on a bus across America, with a runaway bride, into the townships of South Africa, Chernobyl, the Amazon, fatherhood, the deep South, the ups-and-downs of enduring love, questions about mortality, and dreams of the afterlife.

That conversation (and adventure) continues with Stranger to Stranger at the velvet rope of a nightclub, with a homeless “street angel,” in a hospital emergency room, at the riverbank, an insomniac’s bedside, and a village in central Brazil that some might describe as a “thin place” — where the veil between this world and whatever lies beyond it is like gossamer.

Simon, who turns 75 this year, hadn’t made the journey to see João de Deus because he was physically ill. In fact, he’s in pretty great shape. But he has suffered from violent nightmares for most of his life and in the months leading up to his unlikely pilgrimage, the bad dreams had become more frequent — sometimes once or twice a week.

“I was kicking and punching in my sleep,” Simon said, “and Edie was saying, ‘You better go down there.’”

He traveled to Brazil alone and checked into his single room at the Posada, a simple hostel-like lodging affiliated with the John of God ministry. He didn’t take much with him — a couple of books, his laptop in case he wanted to write anything, and his cell phone, which was about as useful in the remote Abadiânia as a subway pass.

Unplugged and largely off the grid, as is the custom for visitors, the singer donned all white (think an afternoon of lawn bowling, not Druids on the Salisbury Plain) and joined the queues for an audience with the healer.

No special treatment. No entourage. And no guitar.

‘Your Suffering Is No Less Important’

For more than 30 years, pilgrims from all over the world have traveled to Abadiânia seeking miraculous healing from João de Deus, who has no medical training and only two years of formal education. He is perhaps best known for performing physical surgeries with only rudimentary tools — forceps, a simple scalpel, tweezers, or just his bare hands — to remove tumors, scrape people’s eyeballs, and pull various viscera out of their noses.

It all sounds rather horrific (as evidenced by several documentary videos that are not for the faint of heart), but reportedly patients experience little bloodshed or pain despite the absence of even topical anesthesia.

“I was standing on the line and waiting, and I thought to myself that this doesn’t feel right. I really don’t feel like I belong here,” Simon recalled.

“Then I was thinking, my mother she would probably be furious that I went and my father would probably just think it was stupid. But anyway I waited,” he said.

The Casa was filled with pilgrims, many of whom were disabled or visibly unwell, including cancer patients suffering the effects of chemotherapy. “And here’s me who’s not sick, but I’m there and I think, look, if I have anything to ask, I’ll ask why I’ve had violent nightmares since I’m four years old.”

After his “spiritual surgery,” Simon returned the Posada and slept for 18 hours. During his time in Brazil, Simon said he meditated on his nightmares — exploring, in his mind, what and whom he saw in the recurring dreams that often took place in and around his childhood home in New York.

“They say there are some people who, like, cling to you and they’ll keep coming back in the dream,” Simon said. “They want something from you. And they’re hard to get rid of. And if you want to begin to get rid of them you say this prayer: ‘I’m sorry, please forgive me, I love you, thank you.’ And then you mentally cut the cord. Essentially what you’re saying is … goodbye.”

When he returned to the Casa the second time, John of God invited Simon to join “The Current,” a small group of pilgrims who flank the modest raised platform where the healer sees patients and meditate or pray during the three-hour sessions, while he waited his turn for another healing consultation.

“Finally it’s my turn to come up in the line — I’m the last person that he sees — and I say to my guide, ‘Look, I don’t want anything. There are people here who are really sick. I’m fine. I have bad dreams, but I’m fine. I don’t want anything.”

A translator explains to João de Deus what Simon’s said, and the healer tells him, “‘No. Your suffering is no less important than anyone else’s. It’s not like if we deal with your suffering someone else gets less relief.’ He takes my hand and he says to me, ‘You are a child of the Casa. You will return here three times and you will always be welcome. And would you sing one of your songs?'”

The request caught him off guard, but Simon agreed, someone handed him a guitar, and he began to sing the only one that came to mind: his iconic 1969 song, “The Sound of Silence.”

About 200 people were gathered in the Casa’s three rooms as Simon began walking from room to room as he sang, he said.

“As I walked toward people some people would begin to weep and some would fall down and … I say to myself, ‘Woah, some big energy thing is happening that I don’t understand and it’s happening through me, but I don’t know what it is and nobody told me about it.’ I don’t know whether I’m doing anybody any good. It’s pretty strong so I’m afraid to get too close to people because the closer I get the more they shake,” he recalled.

“Then I start to move over to the [chemotherapy patients] and let them weep for a while. There’s something about this that feels like this is OK. Whatever it is, I’m just playing ‘The Sound of Silence.’ I walk into other rooms and the same thing happens. People fall. They start to weep. I finish the song and hand the guitar to somebody and leave,” he said. “That’s what happened … I don’t know how to describe it. It wasn’t bad. It wasn’t good. It was I-don’t-know-what-happened. I hadn’t experienced that before.”

Simon as Musical Medium

Back in the States, Simon continued to work on “Proof of Love,” the most “spiritually themed” song on the album, he said, one that is laden with spiritual imagery and allusions.

I ask the Lord

For proof of love

Love is all I seek

Love is all I seek

And when at times my words desert me

Music is the tongue I speakSilent night

Still as prayer

Darkness fills with light

Love on Earth is everywhere

Simon's experience with John of God — a not-uncontroversial figure who claims he has no power on his own but that God (and helpful spirits of healers from the past) move through him to heal people physically and otherwise — affected the singer-songwriter in ways he says he hadn't anticipated and still is processing.

He declined to say what had motivated Brickell, his wife of 24 years, to visit John of God’s Casa. But, Simon said, “She had a very strong reaction. More mystical things happened to her. But she’s more attuned to the mystical than I am.”

Still, Simon is drawn to mystical experiences, which, in turn, occasionally make it into his music. Last week he told the sold-out audience at his Hollywood Bowl concert about another trip to Brazil, this one down the Amazon River in the 1980s where he visited a “brujo” who invited him to partake of Ayahuasca — a psychedelic brew said to elicit strong spiritual visions about the meaning and purpose of life.

That experience, he said, led him to write “Spirit Voices” from his 1990 Rhythm of the Saints album.

Some stories are magical, meant to be sung

Song from the mouth of the river

When the world was young

And all of these spirit voices rule the night

A natural skeptic who insists he is not "religious" and had “no interest” in exploring his native Judaism beyond his bar mitzvah more than 60 years ago, Simon admits he is intrigued by the faith of others.

But before anyone tries to nominate him for a Dove Award, Simon insists most of the spiritual imagery and allusions in his work, including Stranger to Stranger, are largely unintentional and likely more in the eye (or ear) of the beholder.

“I don’t think that way,” Simon said. “You know that I believe in [the spiritual] aspect of our nature and that I find it fascinating. That hasn’t changed and so it pops up in the songs. ... For whatever reason this stuff comes through me or out of me or whatever it is and I put it down and a lot of times I just say hmmm. OK.”

In recounting his spiritual adventures in Brazil, Simon also revealed a few intimacies of his creative process.

“It comes from the sounds,” he said. “If there’s anything that’s mystical about the whole experience, it’s the creating of the sounds, the tracks. When I’m satisfied with the way the tracks go, then they inspire a thought or a lyric.”

Simon describes himself as a conduit or an “editor,” a musical medium, if you will.

“I keep trying to be open to what the sound universe is offering, rather than struggling to come up with stuff that’s from my own limited life,” he said.

Case in point: the new album’s opening track “The Werewolf” got its name (and narrative inspiration) from the sound made by an Indian instrument called a Gopichand. “I thought it sounded like the word ‘werewolf,’” he said.

The song “Street Angel,” has an even more intriguing provenance.

“Here’s how it happened: I made the rhythm track … and then I played this gospel quartet from the late ‘30s and I slowed it down in pitch to fit the overtone of the drums, so that made the whole thing get very slowed down. And then flipped it backwards and listening to the sounds — what I heard sounded like ‘street angel,’” Simon explained. “I thought, this is really fun. They’re telling me what to write about.”

More often than not in his songwriting, the sound precedes the lyrics, Simon said.

One exception, however, is a lyrical passage from “Street Angel,” that says:

It’s God goes fishing

And we are the fishes

He baits his lines

With prayers and wishes

They sparkle in the shallows

They catch the falling light

We hide our hearts like holy hostages

We’re hungry for the love, and so we bite

That lyric came to him first, before the music, he said.

“What I wrote down was, ‘God goes fishing and we are the fishes.’ The rest of it is finishing the rhyme and finishing the story. But also the part about being ‘hungry for the love,’ I almost put ‘hungry for his love’ — we hold our hearts like holy hostages, we’re hungry for his love,’ but then I thought there were too many Hs and I didn’t want to do that much alliteration,” he said.

It was a sonic consideration, not a theological one?

“No, it wasn’t a theological question,” he said, “and anyway, it sort of means the same thing.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!