Apr 25, 2013

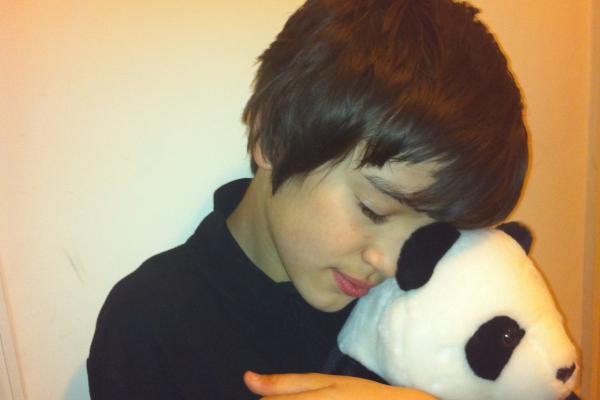

When a distressed child hugs a teddy bear, there is a moment of innocent comfort that not only soothes the child but the grownups around her, too.

No wonder, then, in the wake of the Dec. 14, 2012, mass shooting in Newtown, Conn., the donation of choice for many people was a teddy bear. The bears — huge, tiny, handmade, store-bought, rainbow-colored, traditional brown — began arriving within 24 hours of the tragedy. They came from churches, children's groups, Facebook campaigns, car dealerships, and individuals across the globe.

Undeniably, for some of the children in Newtown — and adults, for that matter — a new stuffed animal was just the right gift at the right time.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login