Faith leaders, historians, and advocates are speaking out after the National Park Service removed its webpage dedicated to Rev. Pauli Murray, a pivotal figure in civil rights history who broke barriers as both a legal scholar and the first perceived Black woman ordained as an Episcopal priest.

“That’s fascism,” said Sarah Azaransky, a Murray scholar who co-authored the application that designated Murray’s childhood home a National Historic Landmark. “It’s trying to erase people and deny their humanity.”

Murray was a legal and spiritual trailblazer

Born in 1910 during the height of Jim Crow, Murray defied easy categorization. In an era when identifying as queer was illegal and dangerous, Murray navigated a complex gender identity that many scholars today suggest would align with transgender or gender nonconforming identities. In personal journals, Murray described themselves as “one of nature’s experiments; a girl who should have been a boy.”

Throughout her life, Murray repeatedly sought medical treatment, including hormone therapy and exploratory surgery to address what we would now recognize as gender dysphoria. In correspondence with family members, Murray self-described as a “he/she personality” and explored different gender expressions. Because of the variety of expression, many Murray scholars use the phrase “perceived woman” when describing Murray’s barrier-breaking accomplishments, and many scholars use a variety of pronouns for Murray.

“Murray didn’t have access to the vocabulary that we have now, but they leave for us these really specific clues about what full humanity looks like,” said Azaransky. “Murray was someone who loved women and was in romantic relationships with women. She’s someone who identified as a woman, but also sometimes someone who identified as a man.”

Murray spent their career fighting for justice on multiple fronts. Murray coined the term “Jane Crow” in 1947 to describe how Black women faced unique forms of discrimination — a concept that would influence critical race theory and Black feminist’s descriptions of intersectionality. When sexism permeated the Civil Rights Movement, Murray responded by helping found the National Organization for Women.

Their pursuit of justice ultimately led Murray to a spiritual calling that shocked many colleagues, Azaransky said. Leaving their secure, tenured position at Brandeis University, Murray entered seminary at a time when women’s ordination remained uncertain. In 1977, she shattered another barrier by becoming the first perceived Black woman ordained as an Episcopal priest.

“For Murray, ordination was very much a culmination of lifelong efforts towards the way that the church spoke about justice,” Azaransky said. “She came to realize that all of what she’d been doing in their law career around human rights was actually the work of the church.”

Efforts to erase marginalized identities

First reported by INDY Week, the digital erasure extends far beyond Murray’s webpage. Multiple federal agencies are removing references to LGBTQ+ identities from government websites, with many now referring only to “LGB” communities — effectively removing transgender, intersex, and other queer individuals from official recognition. Agencies have also removed web pages dedicated to Black Americans and Native Americans, among others.

Behind these changes lies President Donald Trump’s recent executive order targeting what the administration calls “gender ideology.” The directive, which rejects the existence of transgender and nonbinary identities by declaring sex immutable, has prompted federal agencies to purge materials acknowledging gender diversity, from public health resources to historical archives.

The removal of Murray’s webpage has drawn particular attention from historians and civil rights organizations. Angela Thorpe Mason, executive director of the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, noted the contradiction between the government’s previous recognition of Murray’s childhood home as a National Historic Landmark and the current decision to remove online resources about their life and work.

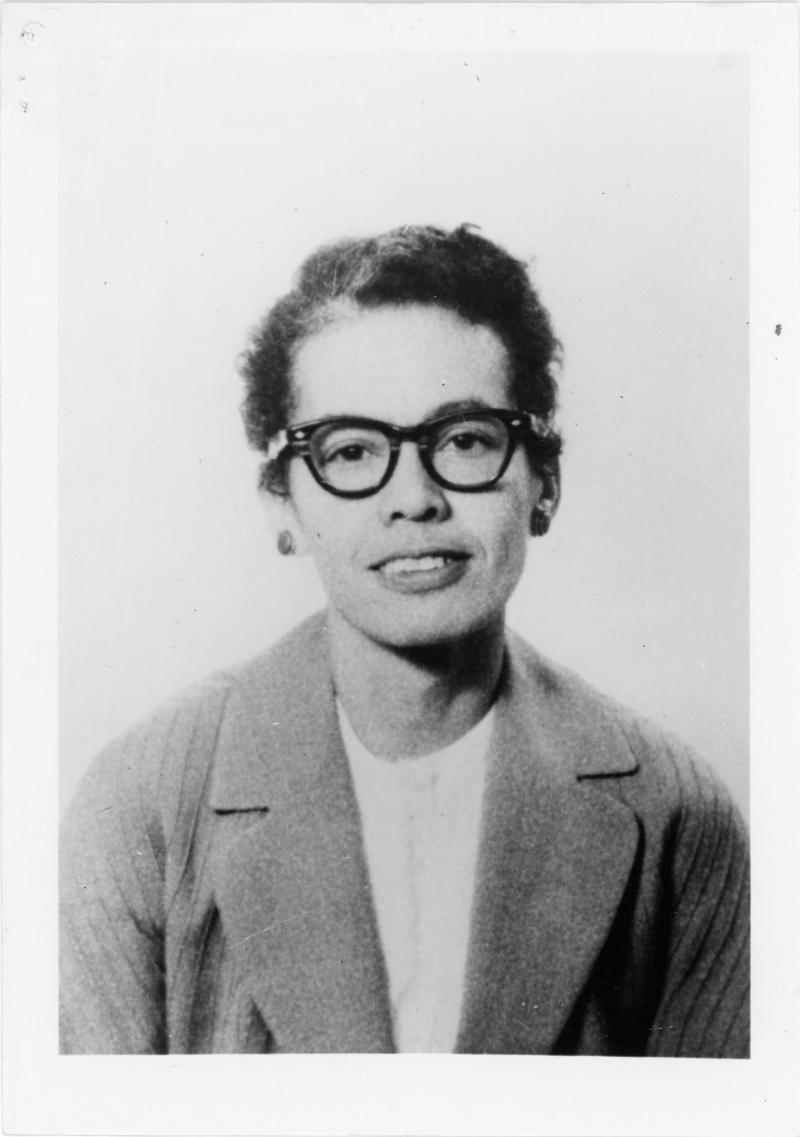

50353256952_32e605ee51_o.jpg

“The federal government had already recognized Murray’s contributions as significant,” Mason told Sojourners in an interview. “Now they’ve chosen to erase and obscure those contributions based on the reality that Pauli was a member of the LGBTQIA+ community. This just paints a picture of why it feels critical to take a stand in this particular moment.”

The spiritual dimensions of Murray’s activism continue to inspire religious leaders today. Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, among the first ten Black women ordained in the Episcopal Church, said in an interview with Sojourners: “I always say, Pauli Murray was a priest well before the church recognized their priesthood. All Murray did flowed from a deep spirituality and sense of who God was.

“I know I wouldn’t be here if Pauli Murray hadn’t gone first,” Douglas, the canon theologian at the Washington National Cathedral, said. “Pauli Murray simply wanted to create a world where ‘Pauli Murrays’ could live and thrive and have their being. That means someone who was Black, embodied female, and queer. That was Pauli Murray.”

Resistance and community education

While libraries, schools, and public materials face increasing restrictions and scrutiny over inclusive materials, faith communities have emerged as important guardians of marginalized histories.

“Our churches should be a sanctuary for the knowledge that is being erased,” Douglas said. “Let’s be a sanctuary for our stories; Pauli Murray should always have a home. Her story should always be at the center of our faith stories, and so we need to preserve that story.”

The Pauli Murray Center offers comprehensive resources to help congregations share Murray’s legacy through workshops, study materials, and digital archives.

The Center has also called on the public to take action.

“We’ve outlined three steps people can take,” Mason said. “First, contact your congressional representatives and urge them to hold the NPS accountable. Second, support the Pauli Murray Center by attending events and using our educational resources. Third, donate to help us continue our work.”

Faith communities can also utilize their collective voice, like the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina, which issued a statement that decried the Park Service erasure, calling it an “affront to the LGBTQ+ community and an assault on Pauli Murray’s deepest convictions about the indivisibility of human rights.”

The efforts to erase Murray have further emboldened advocates to tell the story of Murray and other LGBTQ+ historical figures. “We need to continue to tell our stories. Communities need to continue to tell stories, and we need to continue to develop habits and methods of truth-telling,” Azaransky said. “Every time we speak the truth about Murray — including their absolutely iconic queer status — it’s an act of resistance against historical erasure, and that’s powerful and important.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!