Dec 15, 2015

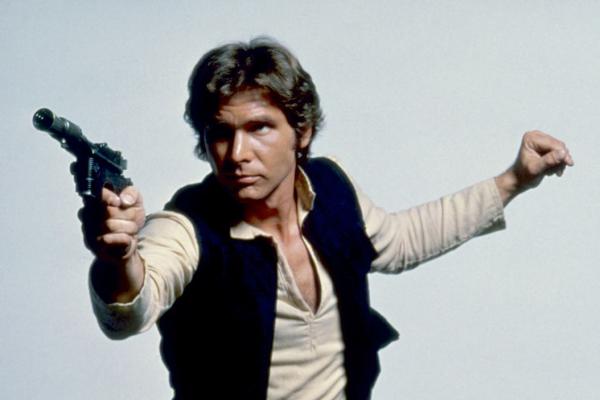

Han shooting first isn’t just a better story — it’s also a truer one. The Bible is full of stories of people being given honors and responsibilities they don’t think they deserve (and to our eyes, definitely don’t). It’s in God’s character to want more for people than they want for themselves. This shows up again and again in the ways God interacts with our world. And we are made in God’s image — when we see this kind of story told well, we respond to it. The original version of Star Wars tells this kind of story about Han Solo.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login