In the nearly 20 years I have been a working journalist, occasionally I have been tempted to intervene in the stories I have been assigned to cover. Most of the time, I have not, and that was probably the right choice. But once upon a time, about four years ago, I crossed the line. In a big way. I intervened because the life of another person was at stake and I knew that my calling was to be human, to react, to help, to do whatever I could to save a life. It's the best decision I've ever made. Hands down.

As I read a remarkable story in the Toronto Star newspaper, I wondered if the paper's veteran foreign correspondent, Paul Watson, now feels the same way.

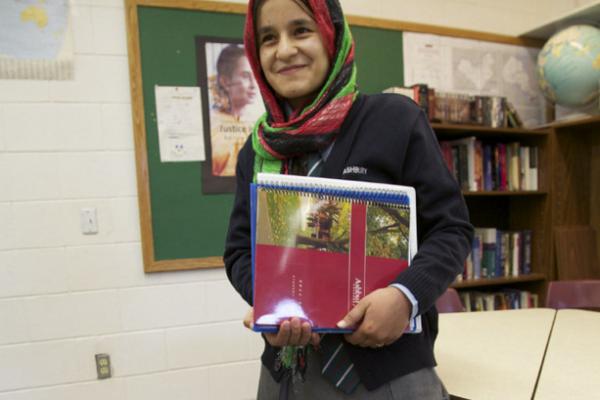

Earlier this month, Watson, who is Canada's only Pulitzer Prize-winner, arrived in Toronto from Kandahar, Afghanistan with a very special package: a 17-year-old Afghan girl forced to flee her homeland, in the reporter's care, to escape certain death at the hands of Taliban assassins.

Read the Full Article