In June my husband, who gets lots of review copies unbidden, asked me if I wanted to read Mark Shriver's memoir about his father, Sargent Shriver, who passed away in 2011 at age 95.

"Since you're a fan of all things Kennedy," he said, "I thought you might want to see it."

I didn't.

True, a high point in my adolescent life was standing in back of St. Matthew's Cathedral one December morning in 1963 waiting for mass to begin when suddenly a very tall, very disheveled, very pregnant Eunice Kennedy Shriver pushed past me, wearing smudged red lipstick and a full-length fur coat. But sons are not necessarily good biographers, and anyway, I had a stack of mysteries awaiting my attention.

But then in July, a Facebook friend pointed me to Reeve Lindbergh's review of A Good Man in the Washington Post, suggesting that this was a book I might want to read. Lindbergh — herself the daughter of two famous parents, Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh — called it "a moving and thoughtful book." Maybe I'll read this after all, I said to myself. And then a week or two later, my friend Estelle sent me a copy of the book as an early birthday present, telling me she thought I'd connect with it on many levels.

I must be supposed to read this one, I thought.

Estelle was right. This is a delightful book for lovers of Camelot — those of us who lived through the suddenly shattered dream of the Kennedy administration. Mark Shriver never saw his uncle Jack (as it happens, Mark was the baby bump under Mrs. Shriver's fur coat at that mass nearly 50 years ago exactly one month after President Kennedy's assassination), and he was only four when his uncle Bobby was shot.

But he grew up with a father who founded the Peace Corps and ran for vice-president, a mother who founded the Special Olympics, four rambunctious siblings, and 20-some cousins, most of whom were unusually energetic and competitive. Mark's childhood home often hosted the rich and the famous, and he recognizes the privilege of growing up well connected. At the same time, he is refreshingly candid about the self-doubts such an environment fostered.

The book, though, isn't about Mark. It's about Sarge, the good man of the title, the father he adored. And Mark's portrayal of Sarge's goodness is what I liked best about the book (and what Estelle knew I'd most appreciate).

See, my father was a good man too. Shriver was an extroverted, energetic, Catholic politician while my dad was an introverted, often tired, Protestant professor; but at core the two men were surprisingly similar. Both were quietly but unalterably faithful Christians. Both adored their wives and children.

Both, though they worked hard and accomplished much, put their families ahead of their jobs. Neither one tooted his own horn, and neither one was bothered when others moved past him into the limelight or up the career ladder. Both men were brilliant, and, sadly, both spent their final years moving into the oblivion of Alzheimer's Disease.

Listen to Mark Shriver read from A Good Man>> [view:Media=block_1]

Mark tells a story about his father that made me gasp in recognition. The two men were in the car together. Sarge "was having one of those lucid moments that make you ... forget for a minute or two that this is all really happening." Mark seized the moment to ask his father a blunt question.

"Dad," I said, "you are losing your mind. You know that. How does that make you feel? How are you doing with that?"

"I'm doing the best I can with what God has given me," he said.

Sixteen years ago I wrote an article for U.S. Catholic magazine about my father's decline and death from Alzheimer's. Here are some lines from that article:

"Are you afraid of dying?" I asked my father several months before he died.

"Dying?" he said, considering. "No, not of dying. I live an abbreviated life."

I asked him what he meant. "A little taken away here. A little taken away there," he explained patiently, as if to a student needing help. "I do the best I can with what's left."

Sargent Shriver was born in 1915; my father, in 1910. Their age cohort is sometimes called the Greatest Generation. Both men were great. Both were exceptionally good.

And I believe both had found the secret of happiness.

LaVonne Neff is an amateur theologian and cook; lover of language and travel; wife, mother, grandmother, godmother, dogmother; perpetual student, constant reader, and Christian contrarian. She blogs at Lively Dust and at The Neff Review.

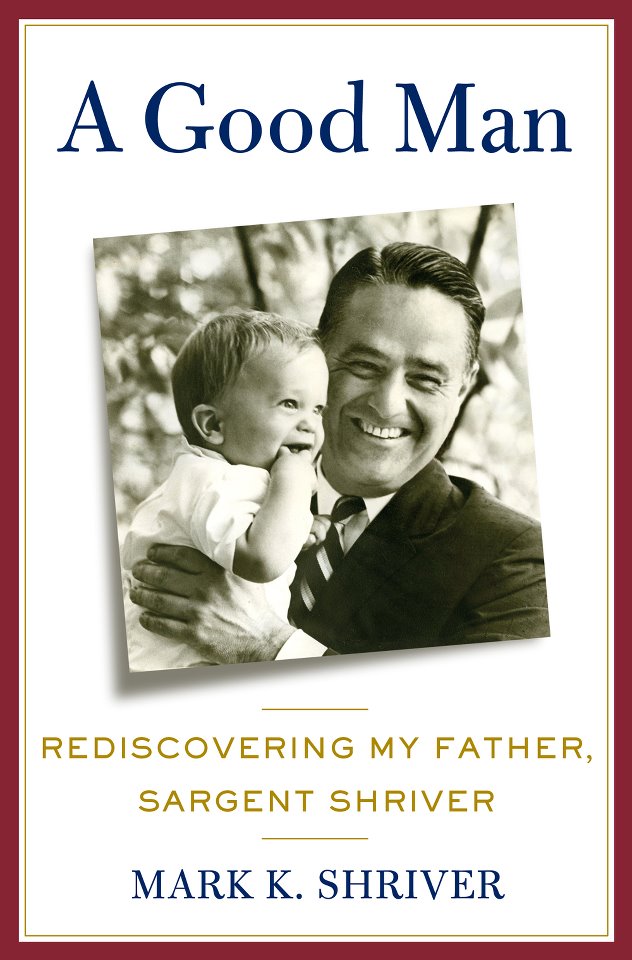

Image: Sargent Shriver in 1961, from the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum [1]; R. Sargent Shriver Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston. Via Wiki Commons.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!