Jun 16, 2016

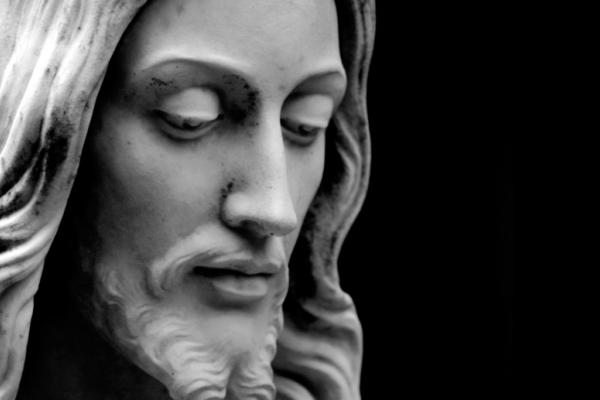

Christian communities get romanticized as places populated with ideal human beings who reflect a pursuit of individual morality in a community of righteous individuals. Yet, in a society organized by race, ideal humanity is always white. Race has calibrated dominant streams of Christianity according to the goals of white supremacy rather than allowing the gospel to calibrate human social interaction toward justice. Christianity scrubbed of justice turned Jesus into a white man, and the gospel into a message of individual morality, calibrated to the language of virtue derived from Jesus as a fetish of idealized white masculinity.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login