Now it should be incandescently clear that no one who has any concern for the integrity and life of America today can ignore the present war. If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read “Vietnam.” It can never be saved so long as it destroys the hopes of men the world over. So it is that those of us who are yet determined that “America will be” are led down the path of protest and dissent, working for the health of our land. —Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “Beyond Vietnam”

Between the first and second sentence of this paragraph, Brother Martin fully entered into his “vocation of agony.”

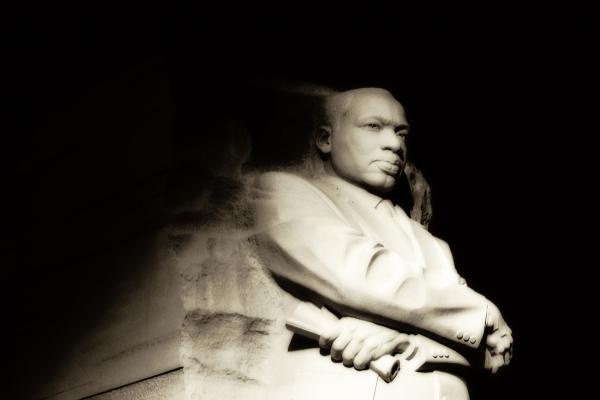

Between these two – the first, where he holds America accountable to the ideals of her founding, and the second, where he begins his sharpest theological critique to date — King “sets his face like flint” (Luke 9:51; Isaiah 50:7) toward the center of military empire: Washington, D.C.

The Riverside speech launches the next phase of King’s ministry. Now he will address the mechanism of empire, not just its bitter fruits. Now he will hold America accountable — not only to her founding ideals, but to God.

In that space between “the present war” and “America’s soul,” an assassin snicked his soft-nosed bullet into a .30-06 rifle.

King names America “Hope-Destroyer;” Vietnam is what the Prophet Jeremiah calls a “high place of Baal, to burn their sons in the fire for burnt-offerings.” (19:5)

God responds to the napalming of sons and daughters with: “I commanded [it] not, nor spoke it, neither came it into my mind.” (Jeremiah 19:5)

King’s Riverside speech was drafted for him by his friend, historian Vincent G. Harding. King made minor changes, but essentially delivered Harding’s original text.

“It’s important to know that for about as long as the war was going on, Martin was raising questions about it,” Harding, who died in 2014, told me in a 2007 interview.

Harding and his wife, Rosemarie, often attended Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta when King was preaching. “It was clear that Martin was opposing the war,” Harding said, “and that he was opposing it from a deeply Christian perspective.”

And so King set his face like flint toward the beating heart of American empire: the arterial flow of weapons, white supremacy, and wealth inequality. King’s gaze on the American symbolic order was disruptive. He looked into the eyes of the master and the master was exposed. Somewhere the assassin adjusted his sighting scope.

In examining King’s speech 40 years later, Harding brought King’s gaze forward in time.

“How does one pick up at this moment the fundamental sense of identity that Martin was working from at that moment?” Harding asked in our conversation.

“The issue for now is not simply how similar the externals are, but where are we in our struggle around certain questions. What does it mean to be a follower of Jesus, the peacemaker, who called others to be peacemakers as a part of our identity as children of the living God?

“We have to ask, what is patriotism? What is nationalism? What does it mean to follow the national leaders into the destruction of others of God’s children? On one simple level it’s the kind of question that dear beloved Muhammad Ali was raising in his heyday when he said, ‘No Viet Cong ever called me Nigga.’ That’s another way of insisting that we not be slaves to the mentality of our leaders and their institutions. What does it mean to take seriously this whole idea that our national identity is secondary to our spiritual identity, and has to come under the scrutiny of our spiritual identity?”

The 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, election, and aftermath provide some data with which to diagnose how America is measuring up — not only to her to her founding principles but, for American Christians, to our confession of Christ and the laws of God.

In 2016, the most experienced contemporary U.S. politician ran against a corporate business executive with no political experience. She ran a campaign that fell well within the mainstream of American politics. He ran an outsider campaign that appealed to the basest human instincts of hate, anger, fear, violence, viciousness, callous disregard for human life, hopelessness, and scorn.

He “won.” Sixty percent of white Catholics voted for him. Eighty-one percent of white evangelicals voted for him. Overall, 58 percent of white people voted for him.

So we return to Harding’s questions: “What does it do to the Christian faith when we recognize that our community began in a setting where most [early believers] were outcasts from the empire’s power? What does it mean when the Christian community now identifies itself with the empire, apologizes for the empire, and goes to war along with the empire?”

What does it do to the Christian faith? Here the “sword of the spirit” slices cleanly: Are we American Christians or Christians in America?

If we are Christians in America, then we must be among those “who are yet determined that ‘America will be’,” as Langston Hughes said. We must 1) gather together with the “outcasts from the empire’s power;” 2) sing poetry, hymns, and spiritual songs among ourselves, singing and making melody to the Lord in our hearts and giving thanks to God in the name Jesus Christ (Ephesians 5:19-20); and 3) be “led down the path of protest and dissent, working for the health of our land,” as King preached.

The assassin may yet pull the trigger and loose the bullet engraved with the prophet’s name. But the whoosh of it as it cuts through bushes and trees with its weak puff of smoke will be overwhelmed by the roar of a living cataract, flooding the land with the justice and righteousness of God.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!