While the world’s attention is firmly fixed on the Islamic State’s continued rein of terror, applause for Malala Yousafzai — for taking home the Nobel Peace Prize — has taken on a quieter tone. Yet, her message — that girls can turn the tide against religious radicalism and repression — risks being lost.

In another part of the world, reports continue to trickle in of the failed negotiations between the Nigerian government and Boko Haram — negotiations that were supposed to include provisions for release of the more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls who remain firmly within Boko Haram’s grip. In fact, there are new reports that another 20 to 70 women and girls have become the latest victims of Boko Haram’s terror, threatening the cease-fire that was to bring the original schoolgirls home. Moreover, much of the world is now eerily silent on the subject — calling into question the commitment to the return of the girls and undermining the separate campaign to improve the education of girls worldwide.

Is this Malala’s world? One where the value of female lives is an open question, and where the kidnapping of girls and women by terrorists goes unanswered? It certainly seems that way. The #bringbackourgirls campaign championed by first lady Michelle Obama and countless Hollywood stars is now a stagnant memory.

Compare this reality to the global push to educate the girls, an understood foundation for economic development and prosperity, with the paradox of the wholesale abandonment of the abducted girls, whose only crime was receiving this exact education.

Despite the U.S.-led coalition’s ongoing military campaign against the Islamic State, its fight for gender rights and the education of girls will take more than F-18s and good intentions. The education of girls cannot be dropped from the sky, and it cannot be a drive-by celebrity cause. It will take protracted American engagement, the kind that brings pressure on Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan and the kind that shifts global interests toward the long-term game of security, of gender rights and education, that makes development possible.

Boko Haram is as much a threat to the women and girls of Nigeria as the Islamic State is to these same people in Iraq and Syria. And neither the U.S. nor the world can afford to allow one terrorist group to go unchecked while (essentially) waging war on another.

Nigeria has become the economic epicenter and largest populace of West Africa, and indeed of the whole sub-Saharan region. The time for the U.S. to act together with the world to rescue the Nigerian schoolgirls (and those recently abducted) is now, when the world is watching, and when its commitment not only to combating terror, but to the rights of girls, and their futures, hangs in the balance.

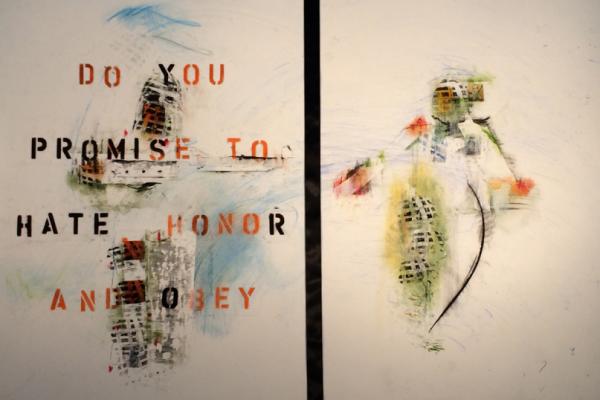

A renewed, coordinated effort by world leaders will signal their continued commitment as much to the release and return of the Nigerian girls as to the value of girls everywhere. It will speak loudly to the 51 percent of the world’s population that their futures are not risked by the latest global crisis — whether that crisis is Ebola in West Africa or terrorist attacks at home. Failure in this area will have a long-term and catastrophic impact on the trust of girls worldwide in promises made.

With much of the world riveted on the atrocities occurring almost daily in the Middle East, we must not forget that intertwined in our efforts to rid the world of radical terrorists are people — in particular those most vulnerable to their activities and atrocities. We must remember what we are fighting radical terror for. The fate of that fight, and of the Chibok schoolgirls, may yet prove one and the same.

Christy Vines is executive director of the Center for Women, Faith & Leadership at the Institute for Global Engagement. Via RNS.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!