“Violence only exists with the help of the lie!”

With these words Fr. Daniel Berrigan and I sealed our fate. It was the summer 1995. August sixth. We’d been invited read at the Washington National Cathedral’s service commemorating the 50th year since the U.S. used atomic weapons on civilians in Japan.

The Cathedral was full. Western light filled the rose window. I was supposed to read an adaptation from Thomas Merton’s scathing indictment of U.S. militarism, the poem “Original Child Bomb,” and the Scriptures for the Feast of the Transfiguration (“Master, it is good that we are here”), also recognized on that day. Dan was slated to read from Soviet-resister Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Prize lecture and from Maximillian Kolbe, the Polish priest who exchanged his life for a fellow prisoner in Auschwitz.

Minutes before the liturgy began, a member of the Cathedral staff called us together to say there was a change in the readings: Thomas Merton was too controversial — I should read from Deuteronomy; Dan should also read from Scripture instead of from Solzhenitsyn and Kolbe.

They handed out a new order of worship. Inserted in it was a statement that included this sentence: “Washington National Cathedral has no official view on the history or morality of the first atom bombs or on any foreign or military policy.”

Dan and I exchanged glances. This could not stand. The opening hymn was beginning. We were pulled into the processional line.

I’ve rarely felt so sick to my stomach. Then it was my turn to ascend the altar steps to the pulpit. I looked at Dan again. He smiled, nodded, and wiggled his eyebrows.

Up I rose.

With the microphone booming, I opened my remarks by saying that it was a travesty for “America’s church” to say that it has no official view on the morality of the first atom bombs; it was a sin for a church to print such a thing. I asked forgiveness from Ms. Hisayo Yamashita, a survivor of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, and other hibakusha, seated in places of honor along the front row.

Instead of reading from Deuteronomy, as was listed in the new order, I would be reading from the original text: Meditations on the Transfiguration, with words from Thomas Merton’s poem “Original Child Bomb” — which I did.

I sat down. Eyes closed. Heart in throat. Face aflame. Silence.

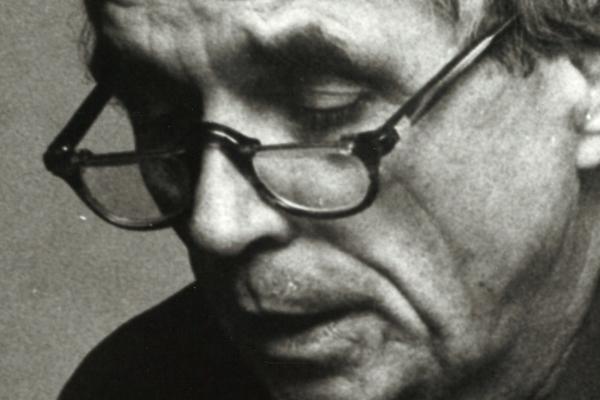

Then came the voice of Daniel Berrigan: “‘Violence only exists with the help of the lie!’ Today in America, this church, to our great shame has perpetuated the lie. What if Christians had taken no official view on the history or morality of slavery …?” For the next 20 minutes, America’s finest poet-prophet-priest called down a litany of condemnation and conscience on the hubris of America’s religious leaders who had lost their way. The straight way had become crooked. Dan trued it in place again.

Following the service, Dan and I were both chastised, yelled at, and then banned from the Cathedral grounds by the person whose “good order” we had “fractured.” Over time the ban was forgotten. But Dan’s prophetic speech lives on.

It’s fair to say that I grew up with Daniel Berrigan.

My father kept a newspaper clipping pinned to the bulletin board over his desk of the Berrigan brothers, Dan and Phil. He taught The Trial of the Catonsville Nine in his high school English classes. In our house, the “Berrigan Brothers” were held up as models of Catholic faith in action.

Historian Gordon Oyer, in his book Pursuing The Spiritual Roots of Protest, writes, “[Dan Berrigan’s] advocacy regarding issues of poverty, open clergy/laity relations, and ecumenical interaction stretched boundaries of the pre-Vatican II Catholic Church and positioned him on its cutting edge.”

Following the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), the Berrigans were paradigmatic of what “new” Catholicism looked like when melded with the genius of America; a genius that was democratic, creative, culturally variegated, thirsting for freedom, liberty, and justice for all.

Sociologist and Catholic priest Andrew Greeley once wrote that the Berrigans were the dividing line between the “old” Catholic social activism and the “new” Catholic social activism. The old Catholic model came out of the immigrant labor union movements, with “worker priests” and community organizing. The “new” Catholic model was born in resistance to the Vietnam War. It focused on aligning with the civil rights and peace popular movements, involving “confrontation and protest.”

Greeley critiqued this new approach: “The old social actionists are largely men of action, doers, not talkers. The new social actionists are intellectuals ... They are masters at manipulating words and sometimes ideas ... They are fervent crusaders. [But] winning strikes, forming unions, organizing communities are not their ‘things,’ they are much more concerned about creating world economic justice.”

In Pursuing the Spiritual Roots of Protest, Oyer recovers a pivotal series of discussions that took place in 1964 that greatly influenced this watershed change in Catholic social action for peace in the U.S. Trappist monk Thomas Merton convened a retreat with 14 members of Catholic (lay and clergy), mainline Protestant, historic peace church, and Unitarian traditions to explore ecumenical collaborations for peace work. Or as Merton put it in his notes, “We are hoping to reflect together during these days on our common grounds for religious dissent.”

Daniel Berrigan and Phil Berrigan were there, as well as others, including John Howard Yoder, A.J. Muste, and Jim Forest. Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King, Jr., were scheduled to attend but King was diverted because of receiving the Nobel Peace Prize. The second day of the retreat was shaped by Daniel Berrigan’s exploration of the Risen Christ and new understandings of the “role of church as protest.” It was at this retreat that seeds were planted in the minds of the Berrigans about public liturgy and direct action.

The conversations with Merton and others set Dan and Phil on a particular direction. The newspaper clipping over my dad’s desk was of Dan Berrigan’s arrest in 1968 at a Catonsville, Md., army draft board and recruitment center, where Dan and eight others poured their blood and homemade napalm on 378 draft files and burned them in the parking lot. Dan led the prayer over the burning draft files: “We make our prayer in the name of that God whose name is peace, and decency, and unity, and love … We have chosen to be powerless criminals in a time of criminal power. We have chosen to be branded as peace criminals by war criminals.” The Catonsville action inspired more than 100 similar acts of protest.

Years later, Dan told me that he’d once been flying on a commercial airline and the pilot overheard his name from the ticket desk. The pilot walked up to Dan and asked if he could shake his hand. “You don’t know me,” he said, “but I owe you my life. My draft record was one of the ones you burned that day. Because of all the mix up, I was never called up. Thank you for saving my life.”

This form of Catholic direct action and religious dissent to the “culture of death” later launched the Plowshares anti-nuclear weapons movement, which began in 1980 when Dan and Phil Berrigan and six others illegally trespassed onto General Electric’s nuclear missile facility in King of Prussia, Penn. They damaged nuclear warhead nose cones (Isaiah 2: “beat swords into plowshares”) and poured their own blood on files to destroy them. As Dan said during the closing arguments of their trial, “In the name of all the eight, I would like to leave with you, friends and jurors, that great and noble word, which is our crime: ‘Responsibility.’”

In 1963, this was the Catholicism I was baptized into: courageous, resistant, self-sacrificing, street-oriented, thoroughly immersed in the living public liturgy grounded in the experiences of those who suffer—especially those who suffer by the design of others. This is the 20th century Catholicism of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, Thomas Merton, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, the Berrigans, Elizabeth McAlister, Antona Ebo, and many others. This is the Catholicism that helped make a person like Pope Francis possible.

Two weeks before Dan died, I was in Rome attending the Vatican’s first global convocation on Catholics, nonviolence, and just peace. At the opening, Cardinal Turkson read a message from Pope Francis reminding us that “our thoughts on revitalising the tools of non-violence, and of active non-violence in particular,” are a needed and positive contribution. “In our complex and violent world,” said Pope Francis, “it is truly a formidable undertaking to work for peace by living the practice of non-violence!”

Following the conference, Fr. John Dear, Dan’s friend and collaborator, flew from Rome to New York to take news back to Dan’s bedside. “He was amazed to hear about our conversations on nonviolence at the Vatican,” wrote John. “So glad I was able to tell him. We had a good visit … but please keep Daniel Berrigan in your prayers, along with this Vatican initiative on nonviolence.”

Dan died a few days later.

In Berrigan’s book on Chronicles 1 and 2, No Gods But One, he concludes with this:

Perhaps it is with relief, sorrowful and secret, that Moses draws a last breath? The forty-year burden, carried with such nobility, is lifted from his shoulders. He dies in a good spirit … Moses indeed can cry out, as a great descendant cried out in our lifetime, ‘I have climbed the mountain; I have seen the Promise. Free, great God, free at last!’”

The mantle is now ours.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!