Poetry

WHEN EMILY DICKINSON first read the novel Jane Eyre, she didn’t know the name of its author. At the time, Charlotte Brontë wrote under the pseudonym Currer Bell, and her work was the subject of controversy. The British Quarterly Review referred to Bell as “a person who ... combines a total ignorance of the habits of society, a great coarseness of taste, and a heathenish doctrine of religion” and said, “the tone of mind and thought which has overthrown authority and violated every code human and divine ... is the same which has also written Jane Eyre.”

When Dickinson returned Jane Eyre to the friend who lent it to her, she sent it with a bouquet of box leaves and a note that makes it clear she’d heard the gossip on Bell. She wrote, “If all these leaves were altars, and on every one a prayer that Currer Bell might be saved — and you were God — would you answer it?” Years later, when Brontë died, Dickinson wrote the following elegy: “Oh, what an afternoon for heaven, / When ‘Brontë’ entered there!”

As Dickinson’s biographer Alfred Habegger notes, this elegy not only grants Brontë salvation but also “made heaven the beneficiary.” Even in these brief notes on Brontë, we can see some of the common themes of Dickinson’s poetry. There is the impulse to engage with (and even affirm) the ideas of God and heaven but also the impulse to subvert rigid and exclusive notions of theology.

I like my anger. I stoke it

like a fire, tend to it

with tender hands, cup

a hand ’round as I

blow to fan the flames

This spring, we’ll gather for a third time

since we first lost our forebears, martyrs to a cause

they did not choose for themselves.

Beloved grandmothers spent their last nights alone

in crowded hospital rooms while officeholders

deliberated over the what, not the what now or the how.

Compulsively larger than life,

mom swaggered out loud.

Her eyes you could get lost in,

and they gripped like a drug.

The Virgin Mary twerking in a thong,

always herself but never the same,

never quite right

but never completely wrong,

she made me feel proud

and destroyed me with shame.

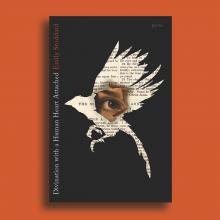

IN EARLY CHRISTIAN gnostic texts, you can read the story of St. Peter’s daughter, who would come to be known as Petronilla. Legend has it that Petronilla was so beautiful that her father prayed she be paralyzed on one side (so that she would not “be beguiled”). In Emily Stoddard’s debut collection of poetry, Divination with a Human Heart Attached, Petronilla is a fruitful companion and the voice of several poems. They appear alongside poems voiced by a contemporary speaker who we assume to be Stoddard herself. In this way, Petronilla serves as a sort of spiritual ancestor for Stoddard. Both look for and lose faith. Both find signs of divine presence everywhere.

While Petronilla’s God speaks in things like “fish and flower,” Stoddard’s confessional work finds God in interior, negative space — not in religious institutions: “I cut away from my body ... slice myself awake to numb arms ... too big to fit inside the church.” She tentatively hopes that “if it’s true, if god is there at all, she kicks us from the inside.” Faith finds form here in ovaries, dreams, the “dark joy” of Stoddard’s dying grandmother finding beauty in “the sunset on the highway.” Unlike Petronilla, whose father fears her seduction by men, the poet-speaker is seduced by poetry — the power of naming things “without the restraint of a scientist.” Names for plants, names for God: “we are not done yet / inventing names / for what will save us.”

Do We Stay or Do We Go?

Women Talking centers on Mennonite women wrestling with how to respond to serial sexual assault by men from their colony. The film explores the complexity of forgiveness and touchingly reminds viewers that leaving one’s community can be an act of faith.

United Artists Releasing

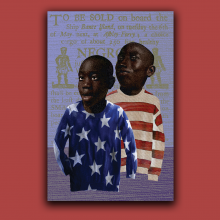

Wrestling with the complicated legacy of Christians and international adoption.

This morning it is minus six degrees.

The old woman at the corner with her bundles

says yes to a ride, but is, at first, unwilling

to say where. Then she does say and tells me

as a girl her grandmother kept three hundred chickens

which she tended every morning before school.

She says a Chinese man would come to separate

the roosters from the hens. Apparently they look alike.

In storybooks there’s no mistaking, but it seems

in real life, one must be outed by his crow.

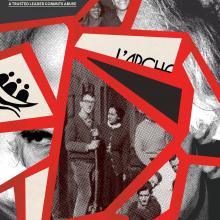

Charismatic leaders such as Jean Vanier can inspire and transform us. But when these leaders commit abuse, how do the movements they ignite pick up the pieces?

I was wrapping up some research in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University when I requested a box of Lucille Clifton’s personal writings. I had not come to study Clifton. I was researching anti-lynching activism in Georgia, specifically a 1936 lynching photograph. But by the end of the week, I began turning to Clifton’s personal writing as an oasis. “Resolve to try to fear less and trust more and be healthy,” she wrote in her red Writer’s Digest Daily Diary on December 31, 1979. Clifton was a published children’s book author, memoirist, activist, and the poet laureate of Maryland when she wrote those words. She was also 43, the same age I was that September day. Her body of work, which includes Two-Headed Woman and Blessing the Boats, crossed oceans, told family stories, and revealed both the sting of injustice and the heart of what’s holy.

The day after Clifton resolved to “fear less and trust more and be healthy,” she wrote in her journal that she returned to a house with “no central heat; bad plumbing; and foreclosure.” A few weeks later, the house was auctioned off to the highest bidder. She sat down and wrote something anyway.

What moved me the most was a tiny hand,

like the claw of a cub, pawing at my

rib cage in time to the suckle of his lips.

This beautiful, wild person sustained

by milk drawn from unknown wells within me.

I remember nursing once in the basement

restroom of the zoo’s primate house.

The floor tile was cold — no other place to sit.

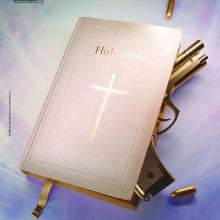

A fringe Christian ideology helped stoke an out-of-control gun culture. People of faith are working to take back the conversation.

My bones have been scraped

free of flesh, free of tendons,

muscles, veins—my heart is gone.

The marrow in my bones

is disappearing fast

and I am fragile,

dissolving into dust.

With a gust of wind

my cells could scatter.

It’s silly to call trees people

saying firs waving limbs are yelling at wind,

and cedars so tall their tops disappear

have heads in the clouds,

or to sympathize with plants below

ripening berries, sending out seeds

on wings while struggling for scraps of light,

and then feeding survivors of fires.

Silly. Better listen. Memorial

services have their ways of bringing up

“Awake, awake …

clothe yourself with strength!”

—Isaiah 52

“What Really Happens When You’re in a Coma”

—Cosmopolitan (Feb. 5, 2019)

You dream I’m looking down on you

like a light on a ceiling

as though you are a thing

and I am a thing,

a light you aren’t,

shining down

on a body

you can’t escape

even in dreams, like this one

in which you dream

you’re awake, trying to awake

to the light that holds you together

The chickens have a meanness I cannot quell

though I thunder from the kitchen window, a god

of rice and oats. No matter how much I scatter

in the cardinal directions, there is bullying,

the Silver Laced Wyandottes the worst despite their name.

Touch me and see, because a ghost does not

have flesh and bones as you can see I have.

—Luke 24:39

So easily startled by vastness, dark

distances, arrival, they were terrified by him

that night glimmering in their midst.

Jesus knew they needed to finger the familiar

relief of bones under warm flesh to believe

the body, pale star

studding their peripheral vision, a specter

rattling even Peter, who had seen the not-

ghost of him before, walking the sea. Jesus

knew their need to know he hungered, tasted

the tilapia baked in olive oil with salt, lemon,

tangy fingers to mouth.

the vast

and all its definitions had dumbfounded. I bit the hand

that fed imagination, took

for pestilence, the flies. For end-of-world, the gully washers.

I shook in handfuls

petals fetched from

doubt

The permanent shiny smudge replaced his bronze face,

his features fade in rusted pictures

I play with pigeon feathers picked from pages

on pulpit splinters that bear his cross of puzzled words.

Warriors unite rage, usher 10% offerings

to dear Black children morning, school wombs empty

Sheets untie laid to rest over waving hands

and church pews ready to fly away with sermons

I am the angel who heard their euphony:

the Hebrew prophet’s words turning to

lamb

topaz on Ethiopian tongue, their voices

wedded together, gleaming

knife

beneath the desert sun. Imagine it:

you are Qinaqis, born beside

ewe

the Gihon River that once flowed from

Eden, marked for exile

mute

from family, from choice,

from even the faith

sheared

you one day will embrace,

despite your pilgrimage through

torment

the wilderness.