Poetry

THE STILL, ATTENTIVE, affectionate, at times lamenting, always sagacious, well-defined, occasional poems in This Day, Wendell Berry’s most recent collection, are a magnificent gift to American letters.

For nearly 35 years Berry has kept the Sabbath holy. His practice is either unorthodox or so deeply orthodox that professional religionists may not recognize it. On Sundays Berry walks his Kentucky “home place,” the roughly 125 acres of bottom land in the region his family has farmed for more than 200 years. From the seventh-day silence, solitude, and natural world, Berry has crafted his Sabbath poems.

“Occasional poems” commemorate public events, but here Berry lays quiet markers to remember personal days in the life of one man. He writes in the preface: “though I am happy to think that poetry may be reclaiming its public life, I am equally happy to insist that poetry also has a private life that is more important to it and more necessary to us.”

Yes, his blood was on us once,

making us famous blades within the blades

community. I mean, many of us

had taken blood and sweat before

from lions and dogs and even fallen birds

or lovers and killers and the killed

but this was the first time we took both

at the same time, from the same creature.

You humans have that saying,

Blood, sweat, and tears. By this you signify work.

Consider the lilies of the field, he said

of our cousins. They neither work nor spin

but I tell you that not even Solomon

in all his glory was clothed like them.

Chiamaka tells of women who plant seeds

of peace in tribal towns, pot-banging with spoons

to call men off their game of raid-and-rape.

A girl named Hope intercepts the hands

of crowing children trading blows

and coaxes them to shake their hands

although her own are quaking. At school

my shy daughter stuffs notes in friends’ lockers,

imploring playground harmony.

Miles of yellow wheat bend; their leaves / rustle away and wait for the sun and wind.

—From “A Farewell, Age Ten”

We wondered what our walk should mean, / taking that un-march quietly; / the sun stared at our signs—"Thou shalt not kill.”

—From “Peace Walk”

WILLIAM STAFFORD was a poet of the land and a conscience that fanned out over the land. Born in Hutchinson, Kan., 100 years ago—on Jan. 17, 1914—it was perhaps his early intimacy with space and sky that opened him to the mystery of human frailty.

At age 6, he saw two black students at his school being taunted by whites. He stood with them.

Another mystery: He who personifies the term national poet is largely unknown in his nation. Four new books (in his 79 years, Stafford published more than 50 books) published to coincide with his centennial might help redress this situation. Ask Me (Graywolf Press), from which the above excerpts are taken, brings to readers 100 “essential” Stafford poems dealing with his pacifism, his family, Native Americans, and the landscapes of his native Kansas and his adopted Oregon, where many centenary events are scheduled to take place.

Recently, I presented this piece at the Christianity 21 Conference in Denver, and then at South Broadway Christian Church later that same week, also in Denver. I’ve been asked by several in attendance to post what I offered, so here’s the text below. The talk was accompanied by a slide show that depicted a combination of Hubble telescope images, electron microscope images and artists/musicians. I considered making that into a video, with me narrating the text underneath, but it takes a lot of time. So let me know if this is something you have particular interest in and I’ll try to make it happen.

In the Beginning

Art Saves lives because art is at the source of all life.

It is the taproot to the dormant breath of God,

Dwelling within all of creation, waiting for invitation.

What we think of today as art is not art.

It has become another product to be consumed,

Rather than a phenomenon to be engaged,

And experience to we have to submit ourselves to,

Allow ourselves to be changed,

And in doing so, catch a fleeting glimpse of

The author, the wellspring,

The essence of what it means to be a soul draped in skin and bone.

[Poem continues after the jump.]

“Belief is as hard as a hickory nut

that cracked holds many mansions.”

—Pat Schneider

If my belief were a hickory nut

I’d keep it safe in my pocket

easy to find with fumbling fingers.

When challenged

I’d take it out

say here, see this.

This is what I believe.

Night.

The sheep huddled against this big rock.

Jake keeps watch while I wrestle with sleep:

—wool prices down, third year

—owner talks of selling out

—Jake and me—Where do we go?

—Martha’s carrying our fifth child

—rumors that Herod’s at it again,

—this time killing babies.

—Same old story:

the Empire trades in fear.

Where can we run?

Like papa says, “I hate being poor.”

The clouds, pregnant with rain. No light

but an inkling of light. If Advent is a time

of waiting, of joyful anticipation, why are we

so often troubled? Consider Mary, the unknown

future she holds. Or Amy, staying the day

with D—, expecting in January, alone and now

spotting with unexpected blood, baby not yet

ready. What was our life before children? Years

of memories now include the children—as if they

already were born, only we could not see them.

And fallen, fallen light renew!

—William Blake

Thou, this humid cloak at dusk, a blue

Air flattened, smoldering the same

Field for years. Oh, Thou—this hardened name

For You not joyously sprung, not grown to grace

One of my favorite stories is about the interview I wanted most, but didn’t get.

It was 2005 and I had just signed a contract to write what would be my first book — a collection of profiles of mostly well-known people about their spiritual lives. Artists. Writers. Thinkers. Scientists. The odd rock star.

Sitting in my publisher’s office, she asked me to dream out loud: If I could interview anyone for the project, who was No. 1 on my wish list?

I answered without hesitation: Seamus Heaney.

When most people think of Gaza, surfing is not the first thing that comes to mind. But photo journalist Ryan Rodrick Beiler has an eye for capturing the resilience and richness of life in this occupied land.

they will kill you

and say I’m sorry

and expect your mother to

forgive and forget

she ever gave birth to you

carried you in love for nine months

endured labor

and pushed you out with God’s might moving in her hips

ever fed you life from her bosom

or how you smelled like heaven after she washed you

that she ever watched you take your first steps

speak your first words

ever tucking you into bed with stories that rocked you to sleep

the many nights she prayed for your protection

or how excited she was the day you gave your first recital

that she ever taught you to be good and kind

ever beamed with pride

whenever you got an A on your test

that she ever wanted the best in this world for you

Early morning

before he unlocks the church gate

the rector kneels before

the gridiron fence surrounding the Cathedral,

not in prayer

but to collect empty wine bottles,

snack bags, and used condoms.

After shoving them into a bag

he turns the latch key and enters the churchyard

shutting it behind him.

The hollow, thunderous deadbolt

echoes through trees like the voices of

ancient saints.

If I were a tree

I would like to be

A giving tree.

Leaves a peaceful green,

Birds could sit and sing,

Children laugh and swing

Upon my branches.

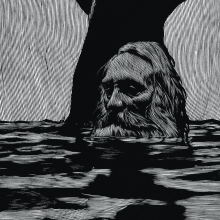

From the midst of the nether

world I cried for help.

—from the Book of Jonah

A gray whale blows off Cardiff Beach,

just beyond the glamour homes,

boutiques, and drive-thru windows,

valet service and all-u-can-eat sushi.

I want to swim out and be swallowed.

Jonah’s whale wasn’t Ahab’s, all

tripey white and peg-toothed, but

a strainer of phosphorescent shrimp,

which lamped the reeking gut, like

fireflies we swallowed once, in jars.

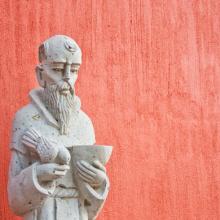

Editor’s Note: The following poem by Trevor Scott Barton was written while he was living in Africa and reading The Little Flowers of St. Francis of Assisi.

Holding you in the palm of my hand

I see your tiny feet and hope you'll live and walk these stony paths

To the pump to get water.

Blessing you in your meekness and gentleness,

You are Jesus to me today.

Kind, tired eyes from too much seeing ...

Worn, battered shoes from too much walking ...

Stained, tattered shirt from too much working ...

Gentle, calloused hands from too much holding ...

Open, humbled heart from too much knowing ...

On my knees I beg forgiveness for my greed—

and for starving myself.

By your eyes I see you love this priest,

follow his lyrical fingers in praise of

a small white host he points here,

there.