Peace

As Father Richard McSorley of Georgetown University wrote years ago, “It’s a sin to build a nuclear weapon.” We once put that on a poster. Perhaps it’s time to put the poster back up.

A starting point is recognizing the truth that war is never noble or courageous. Noble and courageous acts occur during war, but war itself is always the ultimate human failure and must never be portrayed as anything else. War is the expression of our worst impulses — killing and maiming one another while destroying the many good things we've built together.

Liberty and freedom aren’t fancy words or individual guarantees. They’re a process that requires everyone’s participation. We can’t have liberty and justice for all until we’re willing to see the injustice and the lack of liberty all around us, and commit ourselves to doing something about it.

Olcese: In the creation of the film, did you find yourself sympathizing with one character or the other? Was one character easier to make more sympathetic?

Hamm: No. I couldn’t. I absolutely wanted to make the film balanced and fair to both sides. That was completely essential. Don’t forget, both these figures were not liked in Europe before they became statesmen. They were both radical. McGuinness was an ex-member of the IRA, Paisley was a firebrand preacher on the right. These were two men who were pretty much despised universally outside of their own base. It’s like The Odd Couple in the back of a car. I think what the humanity of that is when you take all that away, when you remove from the politician the artifice, and you get a chance to look at them as people, and I think that’s what happens in the movie.

Without any input from the centralized government, the Afghan Peace Volunteers build community and share resources. Within Kabul, they arrange inter-ethnic activities and projects, distribute food, educate children, and manufacture heavy blankets to help families survive the harsh winters. They risk their lives to relate with people whom they are told are their enemies.

In the same-sex marriage discussion, people cite 2,000 years of church history to support their suspicions of affirming theology. But this same history offers plenty of examples of healthy theological shifts that actually counter tradition. Healing on the Sabbath went against thousands of years of history. Replacing circumcision with baptism went against thousands of years of history. Even the Reformation went against 1,500 years of history, with the Reformers’ claim that they better understood the church fathers than the church did. History reveals that the church is always learning, always engaging in a re-examination of core values.

With the blessing of Pope Francis, Cardinal Blase Cupich on April 4 unveiled an anti-violence initiative for this beleaguered city that will be underscored by a Good Friday procession, using the traditional stations of Jesus’ way to the cross to commemorate those who have lost their lives in street violence.

Cupich said he was inviting civic, education, and religious leaders, and “all people of good will,” to take part in the April 14 “Peace Walk” through the heart of the violence-scarred Englewood neighborhood.

We march on Jan. 17 because it is the 40th anniversary of the first "modern-era" execution, after our courts ruled in favor of the death penalty following a decade-long moratorium. On that day, Gary Gilmore was executed by firing squad in Utah in revenge for his murders of Max Jenson and Ben Bushnell. Since then there have been 1,442 other executions. We will hold 40 signs, one for each year since 1977, with the names of those executed each year. We will also carry roses for the victims — both those who have been murdered and those who have been executed — declaring that violence is the disease … not the cure.

So much is at stake here at the dawn of the year 2017. The fate of the planet is in the balance as never before, as is the very integrity of our faith. We cannot waste our time hoping on a faraway unimaginable heaven where there is no war and baby Jesus sleeps safely in his manger.

What we desperately need is the disarmament that Christians and other seekers of peace throughout the world — from Dorothy Day to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. — have prayed and struggled for.

In a time of anti-immigrant fervor, religious distrust, and high political polarization, the peace-building Mennonites in Harrisonburg provide one robust model of how to transcend nationalism and bridge divides. Though relatively modest in size, they are showing how even a small group can affect major, positive change, shaping the hearts and minds of the local ecosystem.

Injustice is at the root of our problems as humans. When people aren’t being treated as equally beloved children of God and are denied equal opportunities for the things we all want, then division and anger grow. If we want peace, we have to be want justice. To be a peacemaker means to challenge the injustices.

Harper’s account of the Gospel in her new book is shalom-based. Drawing deeply from a theme that runs through the Bible but is especially strong in the Hebrew prophets, Harper tells a story of a God who acts in Jesus Christ to bring shalom, or holistic peace and justice, in every part of creation.

“I dream of sports as the practice of human dignity, turned into a vehicle of fraternity,” the pope says.

“Do we exercise together this prayer intention? That sports may be an opportunity for friendly encounters between people and may contribute to peace in the world.”

I SERVED FIVE years as a U.S. Army reserve chaplain. This spring I submitted my resignation to the president of the United States. I refuse to support U.S. policies on armed drones, nuclear weapons, and the policy of “preventive war.” I told the president, “I refuse to serve as an empire chaplain.”

I grew up skeptical of military solutions and decided not to register for the Selective Service System when I turned 18. How, then, did I end up in the Army?

The call to bring my religious values of justice and compassion into the Army chaplaincy came in response to three realities: soldiers burdened by multiple deployments, a military replete with uniformed evangelicals occupying Muslim lands, and the torture at Abu Ghraib.

As chaplain I was pastor: nurturing the living, caring for the wounded, and honoring the dead. However, I also claimed the prophetic biblical imperative to “speak truth to power.”

When I witnessed drone warfare in Afghanistan, my anguish peaked. In 2012, I preached a sermon titled “A Veterans Day Confession for America” lamenting drone killing and “preventive war.” Military commanders reacted harshly. I was discharged with a reprimand and negative evaluation. I learned that U.S. military chaplains are not allowed to have a prophetic voice; they are expected to be nothing more than empire chaplains.

Which has ever brought a peaceful future nearer to neighborhoods: weaponized military and surveillance systems, or the efforts of concerned neighbors seeking justice? The United States withholds resources needed for the task of healing the battle scars our country has inflicted on so much of the world. If our fear is endless, how will these wars ever end?

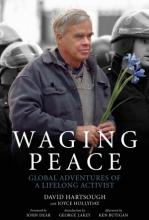

WHAT LIVES THESE two authors have lived and what lessons they can teach us! Reading David Hartsough’s lively memoir immerses us in the great peace and justice events of the last several decades. Colman McCarthy’s fascinating interchanges with high school and university students propel us into a hopeful future as we see how young minds are stretched and carry lessons learned into the world.

Hartsough’s FBI file started when he organized his first anti-nuclear protest at age 15, and it may be growing still as he directs Peaceworkers, a nonviolent training and accompaniment NGO based in San Francisco. In between are 60 years of peace work in the U.S. and the flashpoints of the world, always bringing the message of the necessity and efficacy of nonviolent direct action. In Waging Peace he relives the adventurous life of a professional peaceworker as well as the silent efficacy of his family’s tax resistance and tradition of simple living.

Whether disarming with words a knife-wielding segregationist opponent at a Virginia lunch counter, blockading with a canoe a weapons ship bound for Vietnam, or traveling to war zones, Hartsough has faithfully carried forward his commitment to nonviolence. Sometimes visiting conflict sites before they reach the radar even of other peace people, he writes of going to Cuba, Russia, Yugoslavia, and the Berlin Wall while still a college student, to Central America during the ’80s, and later to Gaza and other war zones.

In 1999, after trying unsuccessfully to persuade the world to support nonviolently the beleaguered Kosovars and thus avert a Serbian bloodbath, Hartsough attended a peace conference in The Hague. There he met Mel Duncan, and together they founded the Nonviolent Peaceforce, now the largest of several worldwide movements of accompaniment for nonviolent activists.

In California, Hartsough worked to launch the huge Abalone Alliance against the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant and campaigned against the development of nuclear weapons at the University of California’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. In this century, Hartsough was one of the first to be arrested for protesting drone warfare at Creech Air Force Base.

THIS SPRING, the Vatican hosted a historic convocation focused on what Pope Francis called “the active witness of nonviolence as a ‘weapon’ to achieve peace.”

Eighty participants from around the world told striking, at times heroic, stories of nonviolent peacemaking at the Rome gathering, convened by the Catholic peace movement Pax Christi International and the Vatican’s justice and peace office.

Many of them arrived directly from situations where they are mediating between violent factions using pragmatic nonviolence fueled by Christian faith—as in Uganda, Iraq, Colombia, and Mexico. Others are engaged in nonviolent peacebuilding in regions recovering from traumatic violence—as in Sri Lanka, Kenya, and the Philippines. Some are active in unarmed civilian accompaniment, shielding people under threat of violence—as in Palestine, Syria, and South Sudan. Theologians, ethicists, and international policy negotiators contributed broader context to the situational experiences.

The conversation focused on four key questions: 1) What can we learn from experiences of nonviolence as a spiritual commitment of faith and a practical strategy in violent situations across cultural contexts? 2) How do recent experiences of active nonviolence help illuminate Jesus’ way of nonviolence and engaging conflict? 3) What are the theological developments on just peace and how do they build on the scriptures and the trajectory of Catholic social thought? 4) What are key elements of an ethical framework for engaging acute conflict and addressing the “responsibility to protect” rooted in the theology and practices of nonviolent conflict transformation, nonviolent intervention, and just peace?

The convocation concluded with an astonishing document, presented to Pope Francis, titled “An appeal to the Catholic Church to recommit to the centrality of gospel nonviolence.” Recommendations included a request for a papal encyclical calling Christians to return to their fundamental vocation of nonviolent peacemaking. That means rejecting just war theory as the “settled teaching” of the church and replacing it with Jesus’ life and teaching as the foremost guide.

“We believe in the value, power, and potential of training to produce more effective, more capable, and better police officers,” the Ferguson Commission wrote. I believe in this, too. And I believe that investing in a better police force may yield a future where “liking the police” is no longer a privilege, but the norm.

Glancing upward at one of the six U.S.-manufactured aerostat blimps performing constant surveillance over Kabul, I wonder if the expensive, high-tech, giant’s-eye view encourages a primitive notion that the best way to solve a problem here is to target a “bad guy” and then kill him. If the bad guys appear to be scurrying dots on the ground below, stomp them out. But crushing only the right dots has proven very difficult for a U.S. drone warfare program documented to have killed many civilians.

We should have no fear of making an apology, which is the outward symbol of an inward change of heart acknowledging and renouncing our violence. We should apologize not only in Hiroshima, but in Nagasaki, Vietnam, Fallujah, Kunduz — around the world, and upon our own shores, with reparations to Native and African Americans.