As a white, Irish, blonde girl growing up in Boston, I was treated well by the police, and for the most part they made me feel safe. In college, I even interned at the Boston Police Department. The officers I worked with were dedicated and professional.

But feeling protected by the police and liking the police are privileges — privileges that vast swaths of the American citizenry do not share. This has been true for a very long time, but now the country sees it more clearly.

I offer this as background for what I’m about to suggest: We need more police officers. We need more and better police officers.

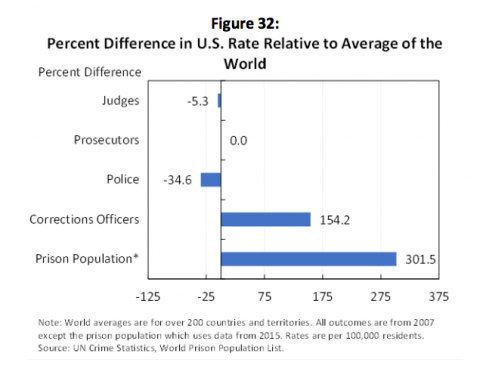

A report published in April by the President’s Council of Economic Advisors offers support for this claim. On page 45 of the report appears the following graph:

Screen Shot 2016-06-01 at 2.54.15 PM.png

This graph shows where the U.S. departs from the rest of the world in terms of its criminal justice system. We employ 150 percent more prison guards per capita than the global average (a determinant of mass incarceration), and 35 percent fewer police officers.

These two points reveal our priorities: Compared to other countries, we invest in corrections, not in law enforcement. And this reflects a broken theory of criminal justice, one that exacts a severe price.

Prisons cost us tens of billions of dollars every year. They also tear apart families and increase recidivism. That’s why I use the word “broken.” And because incarceration so often violates prisoners’ constitutional rights and effectively creates a second-class citizenry, in its current iteration, our penal system conflicts with the spirit and arguably the letter of the 14th Amendment.

In the end, our focus on corrections undermines our justice system, and justice itself.

As does our lack of investment in law enforcement — the evidence of which we see on the news: police officers who resort to violence too quickly, who make fatal errors based on fear and racism. Some officers aren’t fit to wear the badge, and such officers should never be set loose on the streets with a gun. Many other officers are perilously, inadequately trained — agents of a system that decided to invest in corrections rather than law enforcement. This system bequeaths new officers a dangerous status quo, where “good enough” is good enough, idealism is a liability, and racism passes for realism.

Police officers are meant to be “peace officers.” But our lack of investment in their training, resources, staffing, and oversight sets them up to fail. And our emphasis on corrections rather than healthy policing sets up for failure the neighborhoods that need peace most, or the black men who are arrested six times as often as white men, or the children who grow up with fathers in prison.

Here’s the thing – even from a utilitarian perspective the system is broken, because longer, harsher sentencing does not deter crime. Most crime derives from a kind of desperation, internal or external, from a lack of better options. Desperation doesn’t leave a lot of room for the consideration of future consequence. The immediate moment presses in from all sides.

But studies suggest that having more and better police officers out on the street does deter crime. Thus the President’s Council of Economic Advisors argues that a dollar spent on our police departments goes further toward peace and safety than a dollar spent on incarceration, and that community policing, when implemented correctly, still holds promise.

In calling for more and better police officers, the keyword is “better.” “Better” requires an overhaul of the methods and content of police training, which requires willingness, oversight, and funding. That’s what the word “investment” means.

One set of guidelines for such an investment came out of Ferguson, Mo., one year after the shooting of Michael Brown on Aug. 9, 2014. Missouri governor Jay Nixon appointed a commission of leaders and community members to conduct a study of the “social and economic conditions that impede progress, equality and safety in the St. Louis region.” In their report, the Commission details the way the relationship between the community and police suffers when there’s no communication, and the harm caused when police use — or are perceived to use — force in situations that could be resolved peacefully. The report devotes an entire section to police reform, focusing on changing practices around the use of force, training, civilian review, and response to demonstration. It emphasizes the importance of standardized training that recurs throughout an officer’s tenure. And the Commission highlights one of the best approaches to addressing racism (and other –isms) in police forces: implicit bias training.

What’s transformative about implicit bias training is that it acknowledges the prejudice that everyone carries about everyone else, and the way these prejudices and preferences affect behavior — from teachers who are more likely to call on boys than girls to officers who are more likely to use force on black suspects than white ones. And then the training works to undo these biases.

We’ve struggled to make the changes suggested by the Ferguson Commission, in that city and elsewhere. But if practiced painstakingly across the country, these changes would begin to mend the relationship between the police and the communities they’re supposed to protect.

“We believe in the value, power, and potential of training to produce more effective, more capable, and better police officers,” the Commission wrote.

I believe in this, too. And I believe that investing in a better police force may yield a future where “liking the police” is no longer a privilege, but the norm.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!