Living the Word

THE LECTIONARY PASSAGES for these weeks of Pentecost make the season come alive. Why? Because who doesn’t light up at receiving gifts? We humans are pretty good at giving gifts—Christmas, birthdays, graduations. Yet our giving pales in comparison to that of the Holy Spirit. Usually we give because we expect something in return. The Holy Spirit gives freely and abundantly out of unending love and grace. These scriptures tell of the Holy Spirit giving us all we will need to lead God’s people: happiness, tongues, humility, and boldness. And yet we’ll also get more than we need: The Holy Spirit both gives and empowers.

For the work ahead, we will certainly need a power that goes beyond ourselves—unless we are satisfied with half-baked sermons, timid leadership, and time-bound visions. In case this sounds like your grandmother’s preacher on the “fruits of the spirit,” remember that the Spirit put on display in these verses is the prophetic, justice-loving, reconciliation-seeking third person of the Trinity who anointed Jesus with his mission. His was a mission “to bring good news to the poor ... to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor” (Luke 4:18b-19). What a politically theological imagination, capable of transforming the world! It’s the same one the Holy Spirit gives to us today through the church for the world. That’s a gift worth dying for. Holy Spirit come, come quickly!

THE DOG DAYS OF SUMMER can make for a preaching desert without an oasis in sight. This can be a fine time to take a vacation from the lectionary. Huge swaths of scripture go untreated otherwise—the entire Samson cycle, most of the cursing psalms, most of the gospel of John. One friend spends a portion of every year preaching through blockbuster movies and how they intersect with the scriptures. Another devoted a preaching series to favorite children’s books.

Here in August the lectionary itself seems to take a vacation, visiting the discourse about bread in John’s gospel, inviting us to see every bit of bread, every bite of food, as filled with Jesus. Texts about water invite us to see all water as a sign of the God who creates us in the water of a womb and gives water for our salvation in baptism (an especially apt teaching point for those still sandy-toed from the beach).

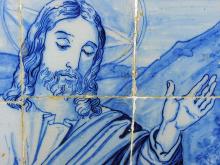

A friend’s pulpit has on it “tree of life,” written in Hebrew—inviting all to see trees as reminders of the tree from which our first parents ate fruit forbidden to them, the tree on which Jesus was crucified, and the tree in the City of God whose leaves are for the healing of the nations.

IN THE LECTIONARY PASSAGES for these weeks following Pentecost, we find God working in and through the ordinary: a shepherd boy, bread, dancing. In each passage God breaks through with incredible revelation; some promise, some challenge, some person unexpected. Not everyone in the passages notices. Paying attention is crucial. We’ll have to be open to being caught off guard, being surprised. The Holy Spirit gives us eyes to see. As we engage in leadership and ministry these weeks, what we are sure to find is Jesus showing up in all the places we might not expect, when we’re washing dishes, driving in the car, eating a meal. And we certainly don’t expect him in the faces of the white poor, in the lives of racially profiled black youth, or in the stories of the undocumented.

We bring into worship our vestments, our commentaries, our manuscripts. God speaks through these—no surprise there. But God grips us in these unexpected places. These are what we should carry with us into worship every Sunday. But we will need more than eyes to make them preach; we’ll need power. The Holy Spirit gives that too. It makes the heart come alive. The gospel artist Fred Hammond said it best: “When the Spirit of the Lord comes upon my heart, I will dance like David danced!” Dancing and singing shape the heart of God’s new community, for joy, for freedom, for hope. May we be open to the Spirit’s vision and boldness!

THE SEASON AFTER Pentecost is a challenge. Some churches call it “ordinary time.” This is where most of our life is lived, spiritually speaking. The fact that other churches call it “the season after Pentecost” reminds us that a miraculous tongue of fire is needed for any sermon to work—and the Holy Spirit has a tongue of fire for us. Pentecost propels us through ordinary time. The Holy Spirit can take as sorry a lot of losers as the ones Jesus chose as disciples and turn them into apostles, martyrs, world-changers. God has always done more with less-promising material.

A retreat at a monastery gave me a glimpse of what ordinary time means. By the time 8 a.m. Mass rolls around, we’ve already been in church three times that day. Mass is beautiful, we leave buoyantly, the Trappist monks are nearly chatty. Then the bell rings. It’s time for Terce, another hour of prayer. That bell sets me to sighing—weren’t we just in church? Terce is like the Sunday after Easter or Christmas—a letdown. Same building, half full of people, and with a quarter of the energy. And it is precisely then that it’s important to worship God. The church’s worship of God carries on when we’ve all gotten bored or tired. Such worship is good for souls. Preachers’ souls included.

BY THIS TIME in the church calendar, the liturgical highlights feel like they’ve slowed considerably. The excitement of Easter is gone, not to be replaced by another holy season until Advent. Pastors and parishioners, who all stayed away the week after Easter, hopefully have returned. The holy days seem to have drained away into the season of counting the weeks, depressingly named as “ordinary time.”

Ecclesially speaking, however, the holy days are amping up considerably at this point. Easter season hits a crescendo with these latter weeks. The ascension of Christ used to be marked as one of the greatest feast days of the year, up there with Easter, Christmas, and Pentecost. It signifies Christ’s rule over all things, hidden now, to be full-blown and publicly obvious to all in God’s good time. Christ himself insists that he must go away in order that the Advocate would come and, in John’s language, to enable us to do even “greater works” than Jesus ever did. Pentecost is a new outpouring of the triune God to empower the church to do those greater works. There is much here to be celebrated. A crescendo, not a tapering off.

These texts present a reign inaugurated with resurrection in which the poor eat and are satisfied. One built on friendship and common love. It suggests a God who likes getting born enough that God decided to go through the experience and told the rest of us we should go through it all over again. Is that bodily enough for you?

DURING THE EASTER SEASON, the first reading in our lectionary becomes, strangely, a New Testament reading. Most of the year, we immerse ourselves in the scripture we share with the Jews, but after the resurrection we traipse through the book of Acts. The claim being made is that the history of God’s chosen people continues in the history of the church. God is still working signs and wonders. And these include the sharing of goods in common, the fact that there are no needy people among us, bringing awe and distress among our neighbors, and a dawning kingdom brought slightly closer. Just like in our churches and communities today, right?

These Easter texts are also deeply sensual and material. God’s reign is imagined as a banquet with rich wines and marrow-filled meats. Love between sisters and brothers is like oil running down the head, over the face. The resurrection texts themselves insist on this point more emphatically than any other: Jesus is raised in his body. This is the beginning of God’s resurrecting power breaking out all over the creation God loves. What could ever be impossible after a resurrection? Our limited imaginations of the possible (Can we make budget? Can we get a few more votes on this bill? Can we improve lives in this neighborhood?) are shown for the bankruptcy in which they are mired. A new order is here. We pray, God, make our imaginations match the sensuousness, the materiality, the grandeur of what you have already accomplished and, more daringly still, what you promise yet to do.

ONE OF THE UNANTICIPATED effects of our health-care technologies is that we expect to live relatively pain-free lives, physically speaking. In the West, we do not imagine a physician saying to us “this will hurt” before cutting in. We expect to be anesthetized to avoid pain. In the same way we struggle with a biblical pathway to God, like Lent.

In Lent, we put ourselves on a lonely road with Jesus—40 days in the wilderness, struggling with hunger, thirst, loneliness, doubt, fear. In Lent, we put ourselves in a 40-year journey in the wilderness with the people Israel, wondering when, if ever, God will make good on the promises of a land flowing with milk and honey. In Lent, we do business with repentance.

Whatever else the church may say about repentance, we certainly say, “This will hurt. And not just a little.” Repentance means “turning around.” It also means dying, biblically speaking. We are drowned in baptism and raised to new life; we go to extremes in the wild until an entire generation dies off (the exodus) and until we are reduced to one searing set of emotions (the crucifixion). Jesus’ cross wasn’t light. Why should we expect ours to be?

Then there’s the good news. A resurrection is on the far side of that cross. Its blinding light pours around the edges of the stone rolled before the tomb. Resurrection is not in Lent, but it’s coming. In the meantime, in the words of John the Baptist, “Prepare the way.”

THE LAST SUNDAY IN FEBRUARY is the first Sunday of Lent. We are asked to prepare for Lent by searching our souls and repenting of our misdeeds in order to walk with Jesus on his road to the cross. After writing the final reflections below, I felt unfinished. Repentance is easy to talk about but exceedingly hard to do. We justify and excuse our actions when we’ve hurt a friend or made a bad choice. It’s usually someone else’s fault anyhow—they started it!

The most striking example of human resistance to repentance I’ve ever read was in C.S. Lewis’ little book The Great Divorce. The “divorce” is the huge gap between heaven and hell. Hell is not fiery but filled with people who can’t get along with each other and keep moving further apart in the darkness. Eventually, a few make their way to a bus stop where they get a ride to the outskirts of heaven. There everyone is met by someone from their past they’d rather not meet, and who begs them to repent, make restitution, or whatever is necessary to enjoy a joyful eternity of loving relationships. For almost all of them, it’s not worth it. They fear losing the bit of ego they have left. They’d rather go back to hell than repent and be reconciled with someone they love to hate.

No wonder repenting is the first step to entering the kingdom of God!

IF WE FOLLOWED the church calendar and celebrated Epiphany in January, we wouldn’t have to cram the wise men into the crèche to compete with the shepherds. We could save all the “Star of Bethlehem” songs to brighten the cold days of January. Obviously, the magi needed a few weeks to prepare and then travel “from the East.”

A new bright object in the sky was certainly an “epiphany,” but it was not totally unexpected. These magi were astrologers, the ancient astronomers of their day. To the east of Jerusalem lay Babylon, birthplace of astrology and location of a large Jewish community. The discovery of two astrological books among the Dead Sea scrolls showed that the sign of Aries the Ram in the zodiac represented the reign of Herod the Great in Judea. Since Herod was aging, it is not surprising that Jewish astrologers were watching this royal constellation.

In a television series called Jesus: The Complete Story, astronomer Michael R. Molnar notes an unusual astrological conjunction on the night of April 17, in 6 B.C.E., the year Jesus was most likely born. At that time, both Saturn and the sun were in the constellation Aries, and then the moon eclipsed to reveal Jupiter, king of the planets, also in Aries. Jupiter shone into the dawn, another auspicious sign of royalty. It was confirmation enough to send these astrologers on their way.

Perhaps if we celebrated Epiphany after Christmas, we’d have more time to learn about this epiphany and its remarkable interpretation.

I CONFESS THAT I do not often use the Revised Common Lectionary. As a Bible professor, I prefer to read texts in their larger literary and historical contexts. When a brief reading from one time period is lifted out of its context and juxtaposed with another written many centuries later, it can feel like an invisible hand is forcing me to compare apples and oranges—or even apples and mushrooms.

Nevertheless, I have been enriched by this year’s readings for Advent and Christmas. My “larger historical context” has become the sweep of a thousand years of Israelite history, from King David to the birth of the “son of David.”

For Christians, the coming of Jesus was a singularity. Though we focus on his birth in this season, that lower-class event was barely noticed at the time, and it is not mentioned by two of our gospel writers. It is his entire life, ministry, death, and resurrection that echoes throughout the ages and ushers in our hope of salvation. Our prophets and psalmists from the Hebrew Bible could not foresee details of the Christ-event from their perspectives centuries earlier. Yet their intuitions and hints and poetic expressions of joy over God’s in-breaking from their times are now borrowed to give voice to our exultation over Jesus’ coming today.

In a culture measured by quarterly profits and immediate gratification by credit card, we need a longer view to better understand what God is doing throughout human history. These Advent readings call us beyond the present to the millennia of the past and the hope of the future stretching to eternity.

WE LIVE IN A TIME of widespread violence. No country, no community, no person is untouched by violence. It is a complex problem stemming from our thought patterns and actions that are, in turn, shaped by various forces in our daily lives. Because violence is so complex, we often seek an easy answer—typically, naming a specific religion, culture, ethnicity, or nationality as a cause of the evil that perpetrates or stimulates violence.

But we all know that such scapegoating is another crime that only creates more violence. Each and every individual and community has good and bad, strength and weakness, merit and demerit. Just as no one is perfectly good, no one is perfectly evil. In her well-known book Eichmann in Jerusalem, philosopher and writer Hannah Arendt points out that evil is related to the lack of reflective thinking. “The longer one listened to [Eichmann],” writes Arendt, “the more obvious it became that his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think, namely, to think from the standpoint of someone else. No communication was possible with him, not because he lied but because he was surrounded by the most reliable of all safeguards against the words and presence of others, and hence against reality as such.”

For Arendt, to think reflectively means to be aware and to take into account the reality that one’s own life is always in relation to the lives of others. This is also what the biblical texts this month invite us to contemplate.

THE PROBLEM WITH Christianity today is not that Christians lack faith in God. The problem is that Christians believe they “know” and “understand” God completely. In a world overflowing with information, we hardly acknowledge the importance of God’s unknowability. Yet a conception of God that doesn’t recognize the unknowable keeps us in an uncritical banality, which in turn leads us to follow orders without questioning, to play it safe, and to go along with mass opinion.

For Christians, conversion is required. Theologian Bernard J. F. Lonergan defines conversion not simply as an acceptance of a new belief system, but rather as “a radical shift from an old horizon to a new horizon.” Religious conversion, in particular, is to “fall in love with God.” Thus, to convert is to deny the conventional, habitual belief and knowledge system, and to discover a new reality in which one becomes open and vulnerable to challenges. Conversion is not a solitary experience. It is a prolonged dialogue that constantly transforms one’s horizon and motivates us to wonder, appreciate, and raise more questions.

The texts for the next four weeks invite us to a conversion experience. They are reminders that conversion starts with abandoning any sense of security based on doctrines, dogmas, rituals, and systems of belief—precisely because God’s love never allows us to find comfort in human constructions.

"Living the Word" reflections for October 2014 can be found here.

ACROSS DENOMINATIONS, Christians have attempted to build a more egalitarian and democratic ecclesiastical structure. The phrase “discipleship of equals,” coined by the feminist theologian Elisabeth S. Fiorenza, suggests that a community of Jesus’ followers cannot tolerate an absolute, centralizing power that justifies a relationship of dominance and subordination.

Yet, while Christians continue to challenge hierarchical structures in the church, we also acknowledge that a discipleship of equals will not be established simply by removing the hierarchy. The church is enmeshed in a concrete reality of everyday life, filled with a web of power relations that are neither fixed nor necessarily top-down.

Power relations experienced within the church are often inconspicuous. They take the form of microaggressions, subtle insults against other members because of gender, sexual orientation, race, class, and ability status. What is even more hurtful is that these insults are often disguised as “caring,” as when someone perverts a prayer request into gossip. The experience of the powers in the church can be paradoxical. Christians must deal with complicated and variegated claims to power, all of which borrow the name of God.

The texts for the next four weeks highlight the struggles in forming a community of God. They raise the question of power relations within the faithful community: How do we use the word “power” and what should be our first instinct in situations of conflict?

AS A NATIVE KOREAN who has studied and taught in the U.S. for more than 13 years, I feel like I’m always swinging between two lands—neither giving me a sense of home. Nostalgia might be too gentle a word to describe this in-between space. Rather, it’s a bitter and unpleasant reality constantly reminding me that to some I appear “strange,” “irregular,” “awkward,” “unskillful,” or “suspicious.” In this situation, I remain “unnatural.”

I often feel the same way in the church. My ethnicity and gender are considered marks of “otherness”—even in my own denomination. Every waking moment I wrestle with this question: How can I incorporate my body, my culture, my language as a Korean woman theologian fully into the body of Christ? This wrestling, while uncomfortable, also prevents me from settling with easy or convenient answers. Perpetual dislocation leads me to pay attention to the unseen and unheard corners of the world. It demands I examine old convictions and construct a creative space for new ways of thinking about God, life, and the nature of justice and hope.

The majority of our biblical stories come from people who were also living outside their own land. They too were in some way dislocated. The biblical texts this month call particular attention to their emotions, tensions, and challenges. They invite all of us to feel lost with them, to tremble with them, and to be courageous with them.

THE CHILDHOOD UNDERSTANDING of the familiar tune about climbing Jacob’s ladder needs a reset. The Genesis narratives aren’t just about heaven—they yield epiphanies into the ordinary life of faith. The household of Abraham and Sarah, even in its ancient context, is atypical. In family dynamics, without the miraculous moments, epiphanies subvert our expectations of whom and what God can utilize to reveal the faithfulness of divine promises. Sometimes the testimony is evident in ordinary lives—even ours. You’ve heard it said, “Our greatest weakness is our strength.” The episodes in Jacob’s life provide sufficient demonstrations of how passions both energize and blind us: Passion or anger; leadership or arrogance; emotion or intuition; determination or stubbornness.

Despite Jacob’s inconsistencies, the second half of Genesis encompasses his story, as the son of Isaac, grandson of Abraham. Here we find an unfolding drama. Characters display human nature at its extremes: conniving relatives, loving couples; creative entrepreneurs, dishonest contractors. All, somehow, used by God to form a people with whom the Spirit so evidently abides.

Even when we go our own way, God’s purposes are not thwarted. The challenge for the church in this Pentecost season is to trust that God is planting seeds in good soil—and the seeds that won’t sprout also have a purpose in this garden. Remember that the actions of justice, grace, and faithfulness we practice at home are as much a witness to God as our public proclamations and protests.

EVER SINCE ADAM AND EVE ate themselves out of house and home, we’ve experienced a brokenness in our lives. Rather than offer praise for God’s wondrous acts, we attempt to build God’s kingdom ourselves. Rather than tell of God’s greatness, we whine that religious obligation demands too much. Rather than involve ourselves in the community, we divide into factions over whether we should work or pray, wait or proceed. Still trying to be more god-like than accepting the assignment to bear God’s image in the world, we attempt to make a name for ourselves. The result? Human-initiated plans cast in language that parodies God’s own plan, pitting human counsel against divine. Setting nation against nation.

Pentecost marks a special occasion in the life of the Christian community. This extraordinary record of what we call the “birthday of the church” is less often noted as the 50th day after Passover—a day to pause, gather, and remember the great acts of God. Passover marks the liberation of the enslaved children of Israel from Egyptian oppression, and Pentecost is the moment “the Holy Spirit is poured out by God ... to empower the church to advance Christ’s mission to the very ends of the earth,” as David P. Gushee puts it.

The Pentecost mission involves patience with God’s timing, which is submission to God’s will. Meanwhile, rather than looking up for Christ’s return, we look for opportunities to be evidence that the kingdom has come.

THERE IS NO controlling a story once it’s out. Even in the times before cell phones, the internet, and Twitter, news traveled a similar route through participants, eyewitnesses, and those with the privilege to eavesdrop upon rumors and reports. Details get scattered, but the facts stand out. Many stories can be told about who, when, and how the story leaked. But all those specifics remain secondary to the spectacular announcement. For example, in 1903, how did The Virginian-Pilotscoop other newspapers to be the first to cover the beginning of the aviation age? No one really knows. Orville and Wilbur Wright believed their hometown Dayton newspapers should make the announcement. Indeed, on Dec. 18, the day after the first flight, the Dayton Evening Heraldreported the news—directly based on a telegraph sent by Orville Wright. But three other papers had already reported this world-changing occasion based on TheVirginian-Pilot’s story. Though filled with inaccuracies, the original accounts correctly announced the single important fact: There had been a flight!

Two thousand years earlier, the witness of a few women called forth centuries of testimonies that describe a progression from lack of recognition to full recognition of Jesus the person, as well as the significance of his death and resurrection. The cross and the empty tomb are not self-explanatory; they require interpretation. On the other side of the Lenten journey, Easter provides opportunities for the church to reflect on the biblical witness concerning the rumors of the resurrection. These texts highlight not only the necessity of interpretation, but also the sources and shape of valid interpretation.

THIS GENERATION IS wired a bit differently than previous generations. I don’t only mean the vitality of portable multitasking devices that provide continuous streams of global news, entertainment, gaming, and random opinions from 2,157 of their closest friends. In all fairness, it’s not their fault. They are who we taught them to be. Often they seek the good, but not God.

Notwithstanding a persistent rejection of organized religion, many in this generation continue to seek power, transcendence, and mystery. Though church membership is down, a steady number continue to express a profound interest in spirituality. In a post-theistic context, says Diana Butler Bass, “many Americans are articulating their discontent with organized religion and their hope that somehow ‘religion’ might regain its true bearings in the spirit.” It’s worth noting that many remain attracted to the idea of Jesus.

These last weeks of Lent invite a rehearsal of faith journeys that lead to rumors of resurrection. Glittering gadgets and tantalizing trinkets will not rid us of an awareness of the futility of our efforts to bring about change. Gossip and trends will not provide Christians with the vitality that facilitates a genuine hope for good. By submitting our ideas of justice to the witness of the reign of God, we pass on the confidence that the faith of the past can sustain us to live into the future. Not only as if there is a God, but as if our God has the power to rebuild and revitalize all that injustice has shattered.

INVITATIONS COME. Yet an expressed desire for your presence does not guarantee your willingness to show up. Invitations require a response. Some responses indicate significant commitment beyond “just showing up.” A summons may first entail an RSVP indicating a commitment to actually take an active part in the opportunity.

Such is the case for the people of God. Invitations arrived inviting God’s people to be witnesses to the power and presence of a particular God and to become a people who practice justice and favor kindness—peculiar expectations for an ancient culture, for any culture. A requirement of this sort unsettles the status quo of cultural mores where religion represents polytheistic attributions to a type of celestial Santa Claus or divine ATM, or where religion has been privatized—set aside from public prophetic witness to meditative reflection in the privacy of our own homes with occasional festive gatherings. Such genie-worship and privatization results in a deafening silence among the people of God. As Pope Francis put it recently, “a privatized lifestyle can lead Christians to take refuge in some false forms of spirituality.”

The promises that God calls us to are promises that Michael Frost, in Exiles, calls dangerous. They accompany dangerous memories that make a dangerous critique of society.

Over the next five weeks, the invitations extended in these texts indicate more than increasing the head count of seekers of spirituality. They require a response that signifies a commitment to participating in a community whose primary purpose is to expose the dangerous promise of God.

EXECUTE: TO ENACT OR DO. Having grown up in inner-city Chicago, I have fond memories of red fire hydrants, swinging jump ropes, and church robes. During summer, the fire department would open the hydrants. Parents granted the petitions of children to run through the streams of water, soaking our clothes and cooling our backs. And while I never achieved the rhythmic agility to jump Double Dutch, I loved to recite the rhymes, which eventually helped me gain a verbal dexterity like that of my pastor. I wanted one day to have a robe like hers—one that signaled that the words I spoke revealed the reign of God.

Turn the clock back. Some children would hold very different memories of fire hydrants, ropes, and robes. In Birmingham, Ala., in1963, the force of the water injured petitioners for freedom. During the American Revolution, a Virginia justice of the peace named Charles Lynch ordered extralegal punishment for Loyalists to the Crown. The swinging rope became the tool of mob violence. And the “hooded ones” continue to use the label of “Christian” to make a mockery of the vestments of clergy.

Fire hydrants. Ropes. Robes. Execute: to eliminate or kill. Meaning conveyed to the hearer may not at all resemble the intention of the speaker. Often communication requires suspension of what we think in order to listen to the context from which the speaker shares. Reading is no easier a task. Sometimes the same letters forming the same word present entirely different meanings. Justice executed. What does it mean?

The context for the next four weeks exposes what the Lord’s justice requires.