Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

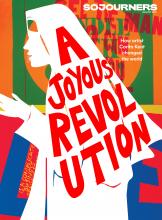

Corita Kent serigraphs: words of prayer (1968), handle with care (1964), mary does laugh (1964), that they may have life (1964) ©2021 Estate of Corita Kent / Immaculate Heart Community / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

FOR SISTER MARY CORITA, the supermarket parking lot in Hollywood she walked through each day to get to her art studio was filled with “sources.” Grocery advertisements, power lines, cracks in the asphalt, songs from car radios—all of these, to her, were “points of departure” that, when examined in a new way, tell us something about ourselves and God. “There is no line where art stops and life begins,” she wrote.

Corita Kent, a Catholic sister described by Artnet as “the pop art nun who combined Warhol with social justice,” delighted in Los Angeles’ chaotic 1960s cityscape. Her serigraphs (silk-screen prints) wrestle with injustice, racism, poverty, war, God, peace, and love in bursting neon and fluorescent lettering, transforming popular advertisements and songs into statements of hope.

“To create is to relate,” Kent wrote in Footnotes and Headlines. “We trust in the artist in everybody. It seems that perhaps there is nothing unholy, nothing unrelated.”

“She broke barriers her whole life, but always with joy,” Nellie Scott, director of the Corita Art Center, told Sojourners. “People often call her the joyous revolutionary.”

Kent was born in Iowa in 1918 and raised in a large Catholic family. Her family moved to Hollywood when she was young, and at age 18, Kent joined the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, who ran the high school she attended. She went on to teach art at Immaculate Heart College, becoming head of the art department in 1964.

The changes going on in both the art world and Catholicism excited and inspired Kent. In 1962, the year that Pope John XXIII convened Vatican II, Kent saw the first exhibit of Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” paintings and dove into the world of pop art. “New ideas are bursting all around and all this comes into you and is changed by you,” she wrote in Learning by Heart.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!