Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

Illustrations by Nico Ortega

IN JULY 2014, the Russian state-owned television network Channel One aired a news story that sickened many Russians.

Speaking from a refugee camp near Rostov, a woman named Galina Pyshnyak claimed to have seen Ukrainian soldiers in the contested Donbas region torture a child while his mother watched. Pyshnyak said, “They took a 3-year-old child, a small boy in panties, in a T-shirt, and nailed him as Jesus to an advertisement board.”

The story, which independent journalists were unable to verify, was quickly called out by international watchdogs as Russian propaganda: a way for the Kremlin to rally support for its occupation of Crimea and — in time — plant the seeds for its 2022 invasion of Ukraine as a whole. The “crucified boy” story served as a call to arms, as cases were reported of Russians who volunteered to fight against those Ukrainians who crucify little children. Subsequent investigations showed that a version of the story had first appeared on the Facebook page of Alexander Dugin, one of the most successful propagandists of the Russkiy Mir (“Russian World”) ideology. Channel One retracted the story in December 2014.

To Netherlands-based theologian Katya Tolstaya, however, the explicit Christian imagery of Pyshnyak’s “eyewitness” account and the visceral responses it elicited throughout Russia represented something else: In Putin’s world, religion and politics were becoming narrowly intertwined.

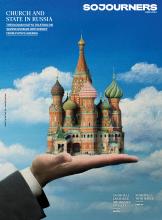

Over the years, experts have produced various explanations for Russia’s return to totalitarianism and who should be held responsible. Some argue the development stems from the ambition and personality of Russian President Vladimir Putin himself, while others point the finger at a broader Russian culture. Assorted studies focus on the political or the historic, the economic or the religious roots of totalitarianism. Tolstaya, for her part, sees religion as both a problem and a solution. Divorcing Russian Orthodoxy from the Kremlin’s imperialist agenda, she argues, can help Russians come to terms with a dark past that they have yet to process.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!