How Artists Are Using Comics to Tell Bible Stories

by Abby Olcese

Icons. Stained glass windows. Mosaics. Epic poems. Songs. Novels. Christian religious art has been part of culture for centuries. But these works have always made statements not just about the biblical events they recount, but also the cultural climate in which they were made.

Our present decade has been characterized by deep divides — political, religious, and cultural. And for the first time in decades, the world has seen a measurably sharp increase in people who no longer consider themselves religious.

In this climate, characterized by institutional challenge and change, what does Christian religious art look like?

Some of the most interesting answers right now come from the comic book world.

These works are telling biblical stories from different, often challenging, perspectives, from creators who place themselves at different spots on the spectrum of belief. Sharing a fascination with the stories of the Christian religion they each grew up with, these artists and writers are making works that allow readers to deeply explore and question familiar stories in the Bible.

New Ways to Tell Old, Old Stories

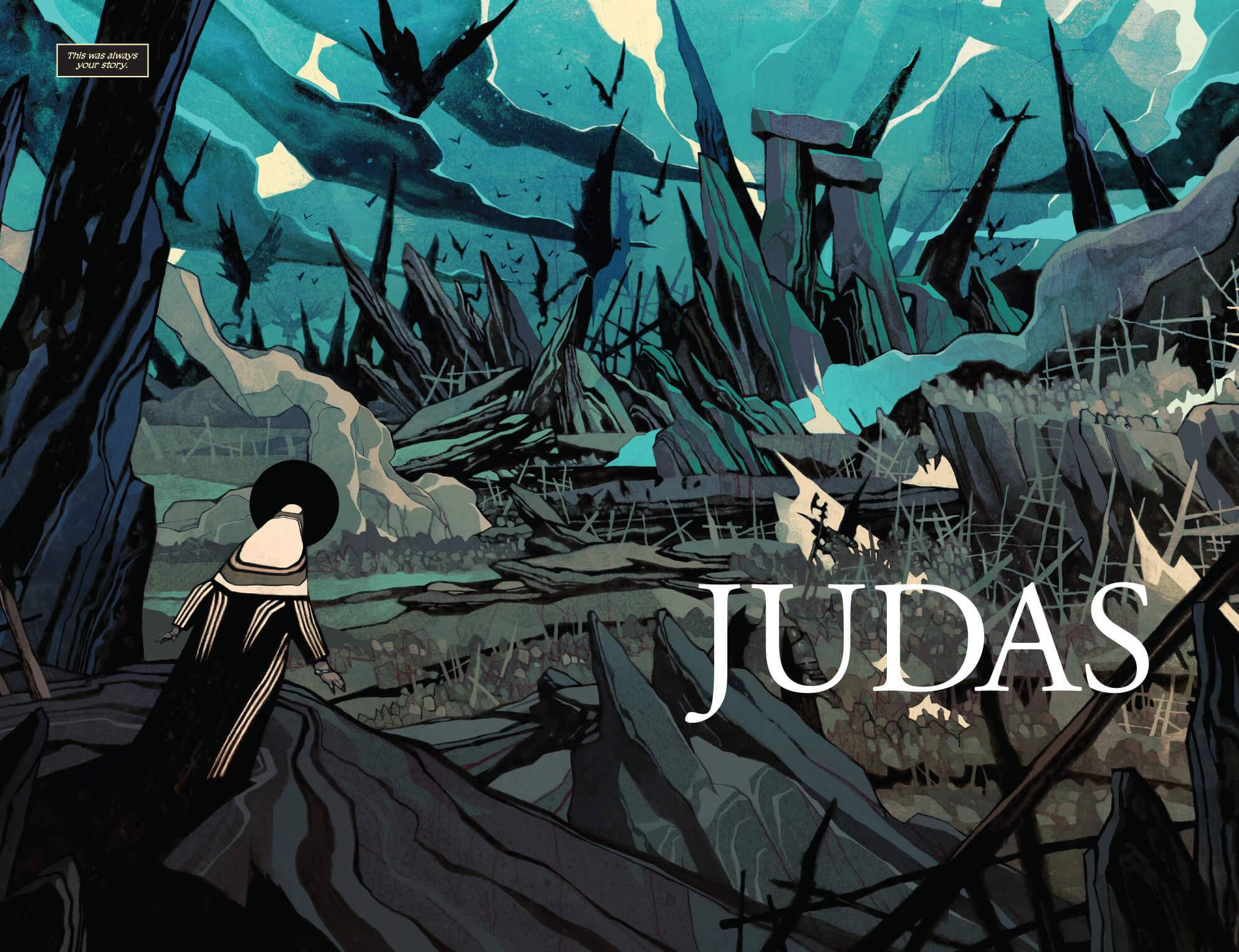

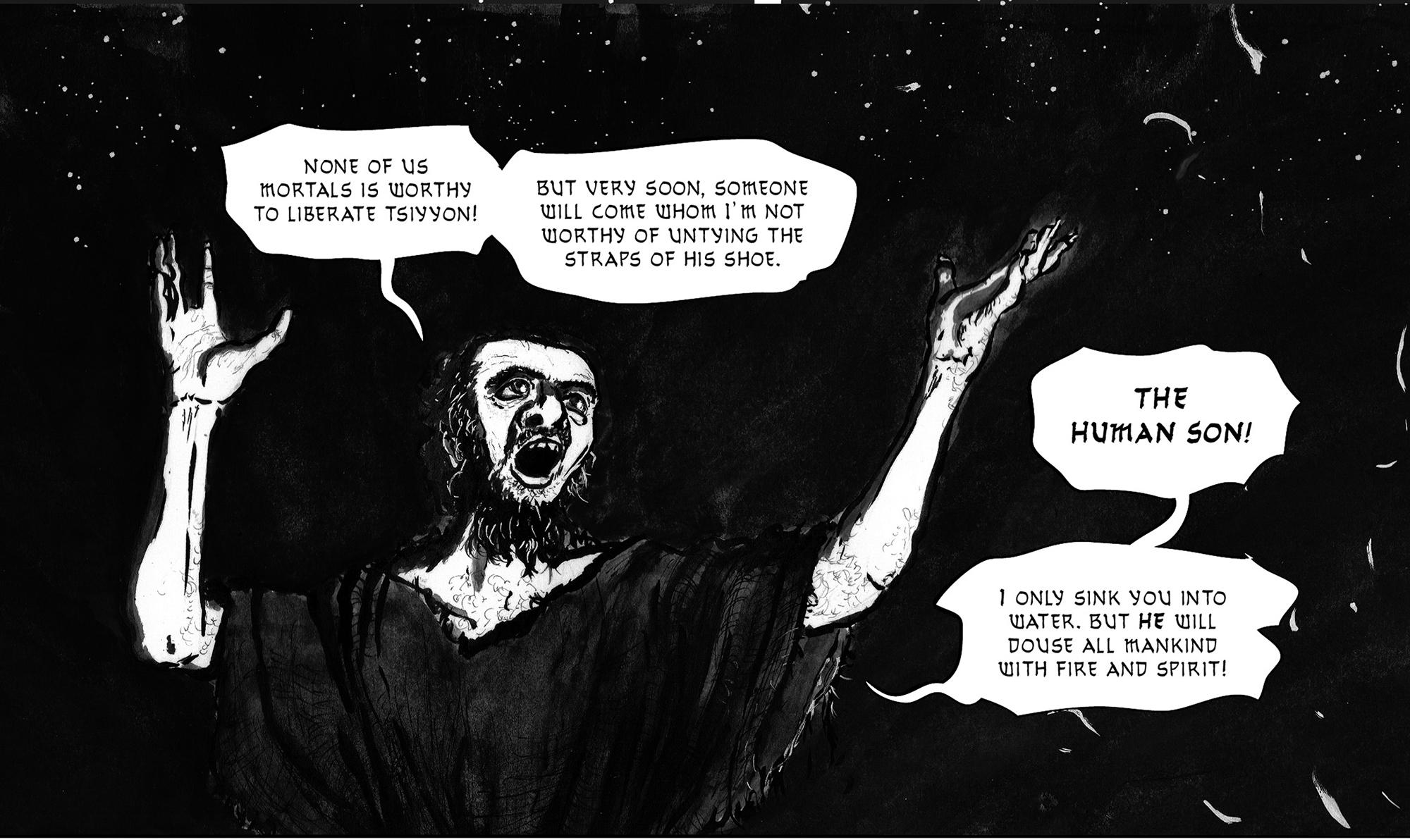

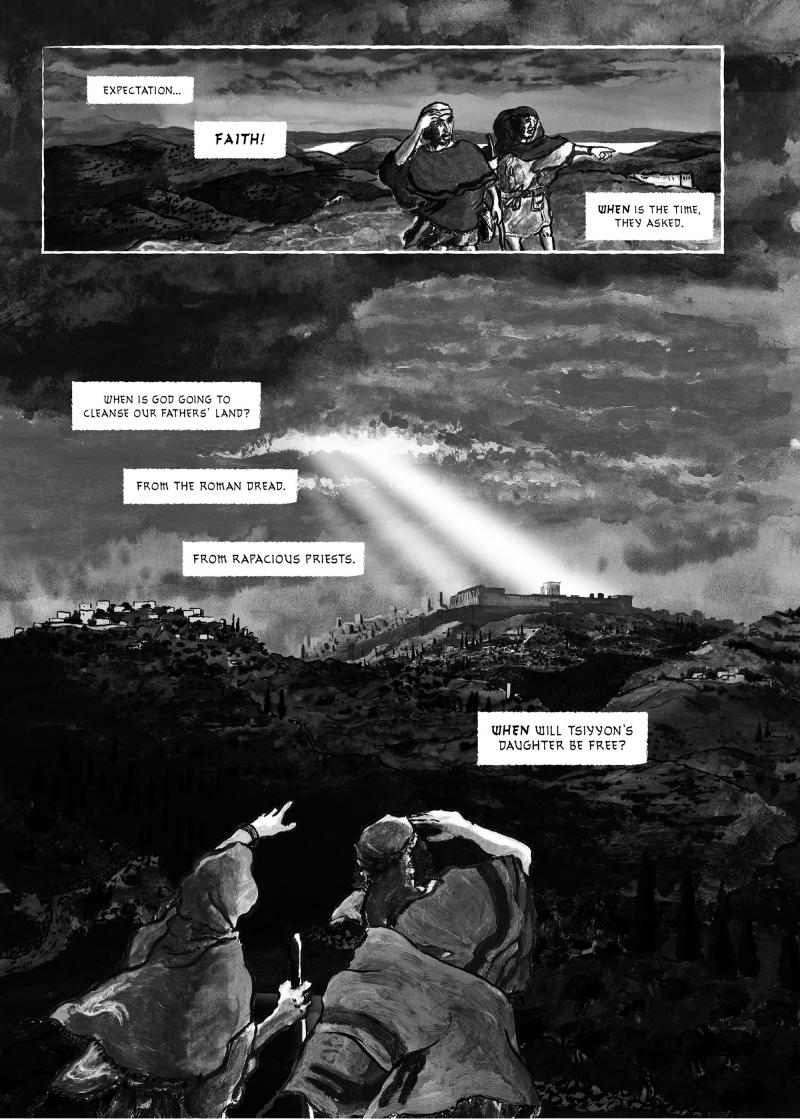

For Issey Fujishima, the writer and artist of The Reign of God (2017), a graphic novel detailing the recollections of an old man claiming to be a former disciple of Jesus and John the Baptist, iconic Western Christian images were something he consciously tried to avoid.

“[Western film and religious art] have given us models for how we imagine these things,” Fujishima told Sojourners. “But for me, personally, I believe they have become too powerful, that we constantly refer back to them and think that’s...how it was. In my own work I try to forget all of that stuff and see what the real landscape is there.”

Based on re-creations taken from the Shroud of Turin, Fujishima’s Jesus looks very little like common Eurocentric images of the Messiah. This Christ has short hair and dark skin, and wears a short tunic instead of a flowing robe.

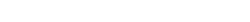

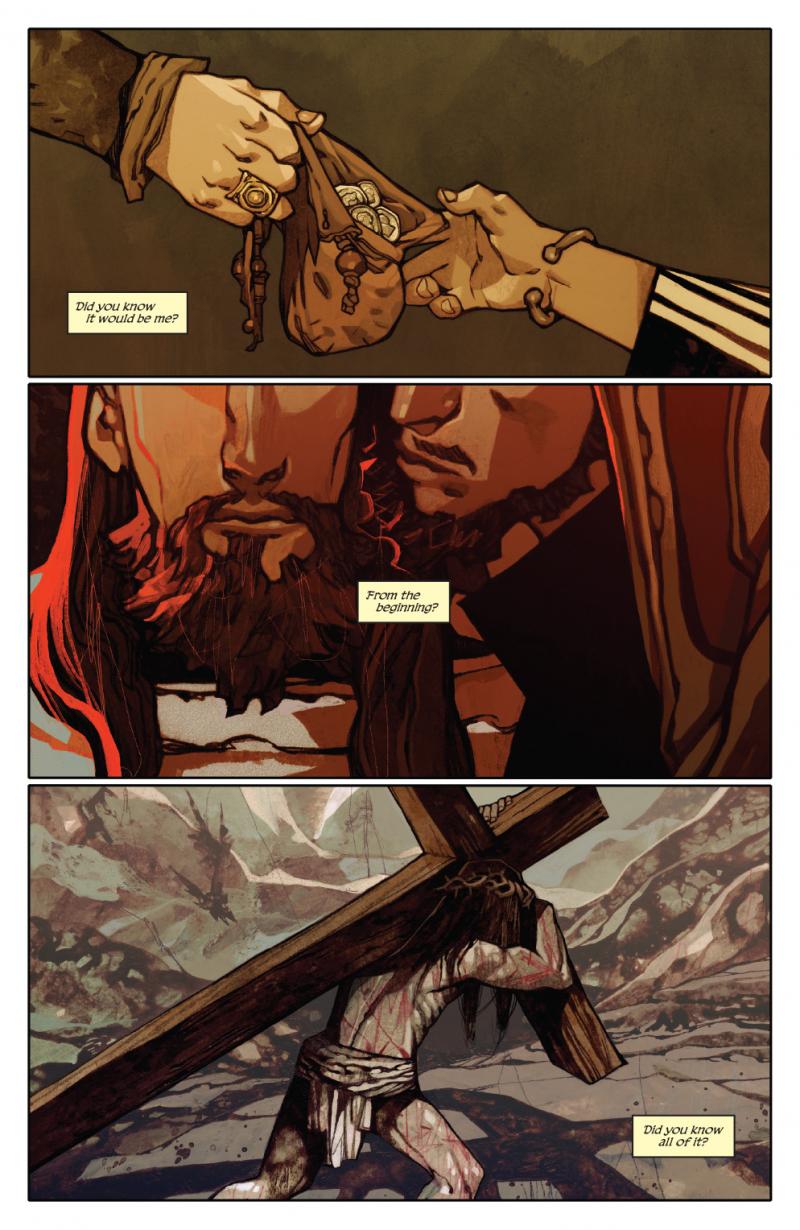

Classic Western religious art did strongly influence the look of Judas (2017-18), which follows Judas Iscariot after his suicide and subsequent descent into hell, though the story sets up different periods and regional aesthetics to collide in innovative ways. Polish artist Jakub Rebelka’s illustrations combine modern sensibilities with inspirations like Dutch Renaissance painter Hans Memling and German Renaissance artist Matthias Grunewald, as well as Victorian painter Richard Dadd. It’s a way for the comic to play with traditional forms, letting readers engage with a familiar story from a new perspective.

It’s a look that Judas creator and lead writer Jeff Loveness says fits his tastes well. “I’m a huge fan of history and I’ve always loved the Christian tradition of art. There’s just so much to pull from,” he said.

Why Comics?

How has a medium known more for superheroes and fantastic adventures become a home for daring, profound takes on Christianity?

The creators of Judas and The Reign of God are using new perspectives, via evocative illustrations, to challenge ideas about how the Bible has been presented to readers, even while maintaining the central concepts that make the Bible so compelling. But Fujishima and Loveness aren’t alone in the comics world.

Jason Aaron’s Old Testament series The Goddamned (2015) also takes on biblical themes in creative, sometimes controversial ways. Aaron’s series uses the undocumented period before the Great Flood as an artistic exercise to speculate on the state of depravity mankind would have to reach to be beyond redemption.

Starring none other than Cain, the series combines an epic narrative with supernatural elements and existing biblical characters to depict a hyper-violent, desolate world on the brink of destruction.

Mark Russell and Shannon Wheeler’s illustrated books, God is Disappointed in You(2013) and Apocrypha Now (2016), encompass the Bible, the Jewish Midrash, the Apocrypha, and the Gnostic Gospels. Combining prose and single-panel cartoons, the books sum up these texts in simple, conversational language — like a scriptural Cliff’s Notes.

Russell, a comics industry veteran, points to the emergence of the medium as a source for mature, thought-provoking storytelling in recent years.

“Comics aren’t seen anymore as disposable children’s entertainment,” Russell told Sojourners. “Things that were hitherto ignored in comics because they were taboo or they were too heady to really be tackled in that medium are no longer off the shelf.”

Loveness says emerging independent publishers like Boom! Studios (which publishes Judas) are part of the trend, creating outlets for more experimental stories.

“There are more places to explore deeper-cut ideas when it comes to religion, instead of just making, say, a book or movie about Left Behind or by-the-book stuff,” Loveness said. “You can use your comics experience and get an indie publisher like Boom! to publish it. It doesn’t have to be through a major studio.”

The stories in the Bible — containing simultaneously vast, society-wide epics and private, domestic examinations of the heart — also lend themselves well to comics’ world-building aspects.

“Throughout the centuries, these stories have inspired a lot of art,” Fujishima said. “The great appeal [of comics] is that it takes us to another world… The [world of the Bible] is as good as a fantasy world, because it’s so totally alien to us.”

Navigating the Bible’s Empty Spaces

To Fujishima’s point, the Bible is full of compelling stories, but it’s often light on details. If we want to understand historical context, or a character’s motivations, we have to interpret it ourselves. This presents an exciting opportunity to use imagination to fill those gaps.

“If you imagine, ‘What could be there?’ — or what could be the reaction, the gaze, the expressions on the faces — if you fill it with life, you see that there is this huge, very human drama that still speaks to us today,” Fujishima said.

In developing Reign of God’s narrative, Fujishima used the work of religion writers like Scott Korb, John Dominic Crossan, and Reza Aslan to help determine how the characters would look and behave. He said his research drove him to want to understand Jesus on a more human level.

“I see a compassion and an authenticity and integrity in his character that is hard to find in other people,” Fujishima said. “I tried to really look at him and his life as a real human being, with real feelings and complicated thoughts and difficult relationships.”

Though Loveness, creator of Judas, says he’s grown disillusioned with the tribalism of the Christianity he grew up with, he still finds inspiration in the New Testament.

“I think there is great beauty and mercy and kindness to be had from the Bible, specifically the teachings of Jesus,” Loveness said. “There’s something so beautiful in the Christian story of redemption and that moment of epiphany ... being able to change your life forever in that moment is such an inspiring and beautiful thing.”

Redemption and doubt are at the forefront of Judas. The four-issue series examines Judas’ guilt at betraying Jesus, the doubt that followed him throughout his life on Earth, and his frustration at feeling forced into being the villain of his own story. Judas also meets Lucifer, who reminds him he’s not the only biblical character whose hardened heart and ultimate suffering seemed divinely directed.

While in hell, Judas also discovers that Jesus is there. In confronting Jesus, Judas comes to recognize his larger role not only in Christ’s crucifixion, but the resurrection story as well. As the comic develops, the story becomes a profound meditation on suffering, hope, and the way those themes define humanity’s relationship with God.

Loveness said he was inspired to create the comic from his lifelong fascination with the conflicting ideas of free will and predetermination present in the Bible, and how those ideas played out in the gospels’ account of Judas’ betrayal of Christ.

“From my perspective, it seemed like [Judas] had tremendous remorse, and from a story perspective it seemed like he was trapped in this story,” Loveness said.

“He seemed like he was an instrument of fate. And once his part in the story was over, he couldn’t handle it.”

Art for a Questioning Generation

These comic book creators, and others like them, are drafting complicated, compelling narratives of Christianity that cut across today's expected divisions. Writers and artists who grew up with Christian backgrounds are finding inspiration in the stories and characters who marked them early on, and re-examining them with questioning minds.

“I realized when I was pitching this series (to publisher Boom! Studios) that I love the language of the Bible. I love the deep, heavy storytelling,” Loveness said. “It was such a huge part of my life growing up.”

God Is Disappointed in You's Russell was raised in the Foursquare Church but left as an adult, saying he now finds inspiration in the Bible’s deeply human construction.

“It’s not just this sort of divinely-inspired tome that comes to us from God, that never contradicts itself, as I was brought up to believe as a fundamentalist. It’s 66 different authors banging their heads against the wall, arguing with each other and trying to figure out what God wants from them,” Russell said. “To me, that’s infinitely more profound.”

Fujishima says creating a Jesus-focused comic has helped him ask deeper questions about the faith he was raised with. Making art has helped him develop a more mature spiritual understanding.

“It’s not enough to just take what your parents or other adults are telling you. If you want to have a faith that is valid for your adult life, you have to emancipate yourself...and find your own answers,” Fujishima said. “I think it’s a very healthy way of finding faith, or finding new meaning in religion. Maybe people right now are thirsty for that.”

For Loveness, writing Judas has been a deeply emotional experience that helped him reconnect with the transformational power of mercy that fuels the gospels, something the writer says he thinks applies strongly right now.

“I always go back to the surrender and the mercy (in the gospel story),” Loveness said. “We just need so much of it now. We need to really amplify mercy as much as we can, and that’s something about the Christian story that I love.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!