Sin

MOST discussions about the Bible and homosexuality are limited to a handful of passages and the subject is viewed as a moral issue in which the burden of proof is placed on lesbians and gay men to defend our right to be who we are in light of those passages. If we approach scripture understanding that heterosexism, like sexism and racism, is a justice issue, then we move to a different plane of inquiry.

We might then understand that what is at stake in questions of sexual morality is not sexual orientation per se but rather the rightful or wrongful use of sexuality whatever our orientation. Sexual sins can occur in both heterosexual and homosexual relationships wherever people are exploited, abused, neglected, or treated as objects. On the other hand, love, commitment, tenderness, nurture, respect, and communication can be expressed in both homosexual and heterosexual relationships.

Spiritual accountability and discipline are slowly becoming extinct within church communities Here are some reasons why:

1. A Desire for Comfort and a Fear of Conflict:

Confrontation is awkward, messy, and just plain hard — so few do it. Additionally, churches and spiritual communities are intentional about creating a sense of peace, encouragement, happiness, and joy — even if it’s a façade.

Identifying sin, exposing immorality, admitting the truth, uncovering corruption, and acknowledging failure contradict the image many churches are trying to portray.

In reality, Christianity was never meant to be comfortable or easy, but in a society obsessed with self-gratification, pleasure, and comfort, churches too easily succumb to an attitude of placation and appeasement instead of responsibility and intervention.

I’ve always had a curious sort of sympathy for the bad guys. I cried when King Kong died. I wept at Darth Vader’s demise. And I felt like the whole melting thing was a little bit harsh for the Wicked Witch of the West.

Maybe they didn’t really want to be bad. Maybe they were just written that way. Could be that they had a rough childhood, or people made fun of them for being green, or big and hairy, or breathing through a big, black mask. I mean, imagine that on the playground …

Ever since my childhood I’ve felt more comfortable in darkness than most kids seemed to as well. My 10-year-old son won’t even go into any unlit room in our house without being accompanied by our dog, Maggie. But I actually enjoyed being in the dark. It seemed like the one place where I could let the otherwise literal, concrete parts of my brain take a rest, and allow my imagination to run wild.

Theologically, we’re taught to hate, or at least fear, the darkness. We are children of light, God called light into being, and it was from this light that all things were formed. So what use do we have for darkness?

Christianity’s most common and subtle sin is … rationalization.

‘Rationalization’ is defined as: an attempt to explain or justify (one's own or another's behavior or attitude) with logical, plausible reasons, even if these are not true or appropriate (Wikipedia).

Essentially, rationalizing is a way of making excuses.

Ever since Adam tried to blame Eve (Gen. 3:12), Moses tried to downplay his ability to lead God’s people out of Israel (Exodus 3), Aaron tried to deflect blame for the Golden Calf onto others (Exodus 32:22), Gideon’s self-deprecation (Judges 6), and Jeremiah’s excuse of being too young (Jer. 1:6), people have rationalized their rebellion to God.

Creating logical, plausible, and valid explanations to justify our sinful actions — or inactions — is easy. We do it all the time because instead of being obviously and visibly wrong, it’s covert, motivated by fear, doubt, shame, and guilt, and mixed with what we assume is intellect and reason — in reality it’s a form of spiritual escapism.

Rationalization is a type of invisible rebellion. It’s hidden not just from us but from everyone. Therefore, it’s rarely noticeable and hardly ever called out. People aren’t held accountable for being reasonable.

But being a follower of Christ often demands being unreasonable.

The first sign I had a problem was when I came across Candy Chang’s “Confessions” project in 2012. It was an interactive art installment on the Las Vegas strip that invited people to come in and confess their deepest secrets anonymously. Those secrets would then be added to a visual art display. It was engaging, unexpected, relevant, discussion-provoking. It was fun.

I hated it.

More correctly, I loved it; and hated myself for not actively doing something similar. I wondered how to implement a version of this idea among colleagues and in office hallways of my organization at the time; I considered “art-bombing” the streets of my city with thought-provoking questions; I spent several moments over the next several weeks seriously questioning whether I should drop everything to focus on Chang-style installations, because I could, and I liked it, and it would work, so I should be doing it. Nothing else I was currently doing mattered. Not without this one thing more.

Welcome to an exhaustive (and exhausting) self-talk: the fixation on never doing enough. Until very recently, I thought this way almost all the time. Somehow — accidentally, almost imperceptibly — years of nurturing my professional and creative pursuits was nurturing something else, as well. It became nearly impossible for me to see work that I admired and appreciated and to not simultaneously think, “I should be doing that, too.”

Which is, simply put, raging covetousness.

Wrath is the only one of the Seven Deadly Sins we attribute to God. And, as pastor Bob, my confirmation teacher in 8th grade would be glad to know I remember, the definition of sin according to the catechism of the Evangelical Covenant Church and similar to most Christian traditions is that sin is “all in thought word or deed that is contrary to the will of God.”

This definitional conundrum raises a few questions. Is it wrong to speak of God’s wrath? Wrong to list wrath among the Deadly Sins? Or are there certain things that are only sins if humans do them but are appropriate to the Divine?

I would argue that yes, wrath can be sinful, but it is not necessarily so. And that during this Lenten season the challenge is not always to suppress wrath but expressing a wrath that is in fact the appropriate response to injustice we see around us every day. In fact, a misguided attempt to avoid wrath can lead to a sin of omission in the failure to practice the “Cardinal Virtue” of justice.

I lust. The words almost seem like they could be a tagline for a new Apple product — an appropriate image perhaps for a generation that is glued to our smart phones. Or perhaps the words are better suited in a kind of Descartes revolution for the 21st century, “I lust, therefore I am.” In either scenario, the words are an accurate reflection of the inescapable truth that lust is consuming all of our lives.

In the church, the word lust has strong sexual connotations. It is a word we are ashamed of and work hard to ignore. When we do talk about lust, it is mostly in the context of uncomfortable sermons or youth group sessions about dressing modestly, not looking at porn, and not gazing at one another with desire. We also often think of lust as a sin that plagues only men — particularly young men with “raging hormones” and that it is something they need to “break free” from.

Essentially the message has become, “If you do lust, don’t; if you don’t lust, good.” But such assumptions do not accurately represent the complex and diverse ways that lust manifests itself in our lives. That being said, I sometimes think that if the seven deadly sins included a clause for a sin that was more deadly, feared, and misunderstood than all of the rest, this would be it.

Sloth. It’s not just a strange, adorable animal we love to watch in videos. It’s also one of the “Seven Deadly Sins,” and one that I find hanging around in my daily life.

I didn’t think about sloth in particular when I chose my Lenten practices for this year, but it turns out to be the very beast (sorry) I’m trying to walk away from.

To be clear, I’m a pretty active person. I walk to work, run long distance, and I’m also very social. But the fact is, every night I look forward to getting home and enjoying what I tell myself I’ve earned: as much time on the couch watching TV and eating as I want. It’s relaxing, I figure, and takes no mental or physical energy.

This is the proverbial sloth in the room.

Yes, unwinding is good, but here’s the problem: I’m not really getting any rest from this. Sure, I’m lounging, and my brain takes a rest if I’m watching something inane; but as a Christian, rest means something different than it does for other people. Rest means Sabbath. Sabbath is the day of the week that we hold sacred, the day when we rest from our usual work and worries, the day that we give back to God and use to worship God. So ironically, my approach to getting the sloth out of my life is to bring the Sabbath into it, at the end of each day.

Our culture's shift around its relationship to shame and guilt can be traced to the broad influence that psychology has had on Western culture over the past century. That is, the reason we have become so sensitized to guilt and shame today in our culture comes from the practical insights of psychologists: As they worked to help people face their hurtful and dysfunctional behaviors, psychotherapists observed that their attempts to help were often met with resistance. Early on Freud referred to this phenomenon as "denial," but regardless of the terminology we use, this is a dynamic therapists have recognized over and over and again because it is, quite simply, one of the most basic elements of human psychology: When we feel threatened we get defensive.

As a result of this dynamic, psychotherapists have found that people actually have struggles on two simultaneous fronts: One struggle is with their negative behavior patterns that hurt themselves and others. The other struggle is the feelings of shame and self-hatred that often accompany these. In fact, the two are frequently intertwined in a destructive spiral where feelings of shame lead to doing things to dull that emotional pain, which then lead to more feelings of shame, and round and round it goes.

I hate the phrase, “Love the sinner; hate the sin.”

To be clear, I don’t deny that God hates sin, or that it has dire consequences, or that it exists, or that everyone does it, or that it’s the reason Christ had to come to earth and be crucified in the flesh. I affirm these beliefs. They are not the reason I hate “Love the sinner; hate the sin.”

I hate the phrase because I think it’s a totally screwed-up, backwards, un-Christlike, and unbiblical way to approach ministry and the world in general.

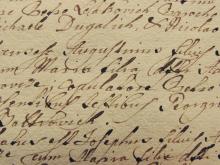

It may be a corrupted bastardization of “Cum dilectione hominum et odio vitiorum,” a quote from a letter by Augustine of Hippo that can be roughly translated as “With love for mankind and hatred for sin.” I have fewer problems with that construction; unlike its modern-day successor, it does not create a subtle but virtually insurmountable divide between speaker and those spoken of.

IN HER LATEST book, Sara Miles—author of the spiritual memoirs Take This Bread and Jesus Freak—goes where traditional and liturgical churches don’t regularly go: into the streets to push the boundaries of public worship. City of God chronicles a day in the life in San Francisco’s Mission District, on one Ash Wednesday when Miles and others from St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church offer “Ashes to Go,” a growing national movement within the Episcopal Church to perform the imposition of ashes outside the church walls on the first day of Lent.

Ash Wednesday works on the street because it has a broad ability to speak to people with “different beliefs about God and very different relationships to the church.” Even so, carrying the observance away from the altar has generated critics. Some liturgists have wondered if, without a proper church context, “the ashes become a meaningless affirmation of our earthly life,” or whether regular folks on the street can really appreciate the profundity of the human condition and mortality without the church to explain it to them. Trusting that people on the street will “get it,” Miles embarked on a day of crossing the traditional borders of worship space to smudge foreheads in McDonald’s, taquerias, hair salons, and botanicas.

Miles finds that traditional observance of liturgies such as Ash Wednesday helps reclaim the public language of sin and repentance in a progressive way. This kind of re-evaluation of sin in common life led her to realize how she’s also fallen short of the call to solidarity and deep communion with the city. “I aspired to be the kind of neighbor who knew everyone,” she writes, “I yearned to be in real relationship.” But her admittedly self-satisfied sense of fellowship didn’t match up to her interactions. She hadn’t even bothered to learn the last name of a young Latino activist on her block and confesses, “I prayed for my neighbors, but not so much with them, and it made me uncomfortable.”

A recent report by OXFAM offered some sobering data about both the concentration and flow of wealth in the world today. A few key points, also summarized by a new business article on The Atlantic website , include:

- The richest 85 people in the world control as much wealth as the poorest 3,000,000,000 people;

- Nineteen out of 20 “G20” countries are experiencing growing income inequality between rich and poor;

- In the United States in particular, 95 percent of the post-financial-crisis capital growth has been amassed by the richest 1 percent of Americans;

- While domestic income inequality continues to grow, the income tax rates for wealthiest Americans have steadily dropped.

My first reaction to seemingly immoral concentrations of wealth, and the systems that enable it, is anger and a compulsion to call them out, to change them and to distribute the world’s treasures evenly among all of God’s people.

But what if we need the insanely wealthy to realize a kingdom-inspired vision for our world?

Every family, including my own, has its “keepers” and “givers.” There are those who keep and hoard every tiny little trinket, every old letter, and every unneeded refrigerator magnet. Then, on the other side of the spectrum, there are others who give away every extraneous and unused thing, living in radical simplicity.

Over the past six years, I’ve attempted to be more the latter than the former. The simplicity movement has been growing for years and is challenging our assumption that more is better. Graham Hill, in a provocative little talk on the topic, has pointed out what our big houses, our lots of things, our endless splurging has done.

Today, the average American has three times as much space as 50 years ago. Our insatiable lust for things has birthed a virtual cottage industry of storage space facilities. The modern storage industrial complex brings in some $22 billion a year. We must learn, Hill argues, to edit our possessions down to what matters and what we actually use. Let the rest go. Clear the artery of our clogged lives.

I CAN’T WRITE a completely unbiased, academic review of this book: Nora Gallagher is a friend, and I know the medical world that she must still navigate, and how wonderful it is when you arrive at the Mayo Clinic. This book is for anyone who plans to die one day and wants to live daily with purpose and with a real God. Those who are or have been physically ill will find a kindred soul in Gallagher, while the healthy will wonder how they will handle the sad, sympathetic gazes from others in the pew when their names are placed on the prayer list.

When she is 60, the vision in one of Gallagher’s eyes begins to fail. She limits the use of her one good eye for fear of losing sight in it too. Not so bad, you might think—except that as a writer, seeing is key to paying for the medical tests and travel she will endure for two years.

Of course all good patients become writers in a way. At first you take random notes in scattered notepads. Finally you redefine yourself as a full-time patient whose life demands documentation of every symptom and test in a little black book that becomes your constant companion. You have now entered what Gallagher calls Oz, the land of illness.

For Gallagher, Oz is strange. Oz is blurry. She is lonely. She is a patient not a person. Oz has many disrespectful, condescending doctors working in machine-like hospital systems that allow 10 minutes for a consult; they must get to the next patient, not solve the mystery of her now-painful, debilitating state.

THIS STORY IS about the loss of a war and the sin and insanity of continuing to wage that war with the same weapon: prisons. From the well-meaning but naive “solution” of “just say no” to the equally well-meaning but equally naive mandatory minimum sentences, we have been defeated in our War on Drugs.

When we finally realized that we had lost the undeclared war in Vietnam, those remaining in Saigon climbed to the highest building and clung to the last helicopter leaving the country. Now it is time for the metaphor to be exercised in the drug war. We have lost.

This year we are presenting the Raven Award on Nov. 12 to Kevin Miller for his documentary with a question for a title: Hellbound?. Autocorrect doesn’t like the question mark, especially when it’s followed by a period, but I’m glad Kevin used it. Because the idea of hell raises all kinds of questions, particularly about the relationship of God to sin. (For Adam, it raises questions about God’s justice – read his reflections here.) For me, the idea of hell raises questions about punishment, like these:

Does God punish sin in this life and if so, how?

Does God punish unrepentant sinners in the next life with eternal suffering?

These questions have corollaries, of course:

Does God reward the righteous in this life and if so, how?

Does God reward a life of righteousness with eternal bliss?

THE ANACOSTIA RIVER is a river of contrasts. Often called “the nation’s forgotten river,” it flows for eight-and-a-half miles through some of the richest and poorest communities in and around D.C., through residential and industrial zones, through marshes and military installations. In fact, the federal government owns so much land in the watershed that when all those federal toilets flush during a heavy rain, they drain directly into the river.

The Anacostia River watershed is home to more than 800,000 people, 43 species of fish, and nearly 200 species of birds—including our nation’s symbol, the bald eagle, and the majestic great blue heron. Yet the trash in the river is so deep and wide at times that you’re just as likely to see a heron walking across a flotilla of trash rather than flying over the water.

As the Anacostia Riverkeeper—part of the Waterkeeper Alliance movement to protect local waterways—it was my job for three years to be the eyes, ears, and voice of its watershed. Of the nearly 200 waterkeepers worldwide, I was the only riverkeeper who was also a minister. I was called “Rev. Riverkeeper.”

The antiquated sewer system that pumps more than 2 billion gallons of raw sewage, mixed with polluted runoff, into the river each year is not just a shame, it’s a sin. African-American churches along the Anacostia used to baptize their members in the river. Nowadays, the river wouldn’t wash away anyone’s sins. My goal as Rev. Riverkeeper was an Anacostia that was not only “fishable” and “swimmable”—as required by the Clean Water Act—but also “baptizable.”

IN SPIRITUAL AND BIBLICAL terms, racism is a perverse sin that cuts to the core of the gospel message. Put simply, racism negates the reason for which Christ died—the reconciling work of the cross. It denies the purpose of the church: to bring together, in Christ, those who have been divided from one another, particularly in the early church's case, Jew and Gentile—a division based on race.

There is only one remedy for such a sin and that is repentance, which, if genuine, will always bear fruit in concrete forms of conversion, changed behavior, and reparation. While the United States may have changed in regard to some of its racial attitudes and allowed some of its black citizens into the middle class, white America has yet to recognize the extent of its racism—that we are and have always been a racist society-—much less to repent of its racial sins.

THE FUNCTION of healthy religion and church is to provide individuals and society with a collective container that carries the objective truth of reality for individuals. The Great Truth is too grand and transcultural to be entrusted to the vagaries of individuals and epochs. Otherwise, society becomes a massive runway for unidentifiable flying objects—each claiming absolute validity and turning their subjectivity into the only sacred.

The ground for a common civilization and shared values is destroyed if our religious experience is basically unshareable or without coherent meaning. We end up where we are today: pluralism without purpose, individuation but no community.