Science

LAST YEAR on NPR’s “All Things Considered,” I heard the story of Teresa MacBain, a United Methodist pastor who came to the conclusion she was an atheist. The situation was scary and awkward for her. Who could she tell? What would she do now for a living?

She wasn’t trained for any other occupation, but neither could she continue her double life of preaching and public praying while knowing she didn’t believe in any of it.

Lacking someone to confide in, MacBain secretly confessed to her iPhone, “Sometimes I think to myself: If I could just go back a few years and not ask the questions and just be one of the sheep and blindly follow and not know the truth, it would be so much easier. I’d just keep my job. But I can’t do that. I know it’s a lie. I know it’s false.” Eventually, she left the ministry.

As I listened to MacBain’s interview, I empathized with her. After 30 years of serving as a Mennonite pastor, I often wonder whether I still believe the things I’ve always said I believed. My questions about God have become deeper, while my previous answers now sound shallow. The thought that I might not believe in God is frightening. It threatens my identity and worldview—not to mention my occupation. And yet I haven’t arrived at MacBain’s atheism. Instead, my doubts have been folded into my faith.

First things first: with all due respect to interim host John Oliver, I for one am thrilled to have Jon Stewart back on The Daily Show. I know it is sad to say, but I actually missed him while he was on summer hiatus. Welcome back, little buddy!

Last night, Stewart interviewed Richard Dawkins, author of The God Delusion, who was promoting his newest title, An Appetite for Wonder. The most interesting moments in the interview revolved around Stewart’s question to Dawkins about whether science or religion ultimately would be responsible for hastening our journey down this path of apparent self-annihilation. What followed was a fascinating, if not entirely satisfying, dialogue about the “downsides” of both disciplines.

CRITICS HAVE BEMOANED the lack of fiction centered on climate change, which seems to mirror our public sluggishness about this scientific reality. But two recent novels, Barbara Kingsolver's Flight Behavior (Harper) and Lauren Groff's Arcadia (Voice), artfully integrate climate change into their plotlines, weaving scientific truth about global warming into the lives of fictional characters. Just as compelling, both works of fiction feature spiritual community at the center of critical decisions about the future of the land and its inhabitants.

Flight Behavior is a lyrical story set in rural Tennessee with the fiercely intelligent Dellarobia Turnbow as the main character. She encounters a vast sea of monarch butterflies that seem to have taken a wrong turn on their migratory path, a result of a miracle—or a warming planet. Journalists, ecologists, and locals speculate about the misplaced monarchs. In an impassioned but measured plea for the land, the local pastor invokes a biblical mandate for creation care.

In Arcadia, climate change doesn't enter the narrative until the conclusion of the story, which is the tale of an intentional community started in the 1960s. The central character, Bit Stone, returns to a failed commune in upstate New York, where he grew up, to care for his ailing mother. Set in 2018, the dystopian conclusion is marked by climate change and global pandemics, but the values of the original spiritual community set up a struggle between the desire for freedom and the creation of shared life.

Books

Faith meets science

- Scientist Katharine Hayhoe and her spouse, evangelical pastor and writer Andrew Farley, gently and wisely respond to the concerns of those who deny the reality of climate change in A Climate for Change: Global Warming Facts for Faith-Based Decisions (FaithWords). An accessible exploration of the science behind climate change and the faith-based reasons why Christians can and must act.

- Ben Lowe, of Young Evangelicals for Climate Action, describes the rise of climate leadership on Christian college campuses in Green Revolution: Coming Together to Care for Creation (IVP Books).

- In Global Warming and the Risen LORD: Christian Discipleship and Climate Change (Evangelical Environmental Network), Jim Ball offers biblical and spiritual resources needed to meet the challenge.

- No Oil in the Lamp: Fuel, Faith and the Energy Crisis (DLT Books), by Andy Mellen and Neil Hollow, is part science manual, part Bible study and points toward a Christian theology for resource depletion and "peak oil." The unexpected foreword by the CEO of a top U.K. energy company adds depth.

- God, Creation, and Climate Change: A Catholic Response to the Environmental Crisis (Orbis Books), edited by Richard W. Miller, collects original essays by leading Catholic theologians and ethicists to give theological and biblical perspectives on our environmental crisis.

- Green Discipleship: Catholic Theological Ethics and the Environment (Anselm Academic), edited by Tobias Winright, is a compendium drawing on scholars from the fields of ecology, biology, history, and sociology, and includes study group aids. It also has the text of "If You Want to Cultivate Peace, Protect Creation," a January 2010 speech by Pope Benedict XVI, which can also be found at www.vatican.va.

- Sacred Acts: How Churches are Working to Protect Earth's Climate (New Society), by Mallory McDuff, looks at local churches' best practices to reverse climate change.

A RECENT RETREAT of evangelical environmentalists raised this theological question: Should we have expected most people in the developed world to hear the scientific evidence proving the great dangers of climate change and then decide to quickly change themselves—their view of the world, their lifestyles and politics—and to withdraw their support from the fossil fuel economy that is threatening the planet and its people?

Those of us gathered at the retreat didn't think so. We human beings just aren't that smart, wise, good, or unselfish. It's more human to deny the evidence, attack the messengers, delay the response, and just hope everything works out. That's what many have done. And since our political system is even more dysfunctional than most of the people it represents—and is bought and paid for by the gas and oil interests that control the economy—the chances are low for courageous and far-sighted leadership.

So what kind of wake-up call will it take to reduce the carbon emissions we humans create, which are warming the earth's temperature and endangering our future in increasingly dramatic ways? Perhaps it will take disruption and devastation—which is becoming the "new normal." So-called once-in-a-lifetime storms are now becoming frequent, with Superstorm Sandy only the most recent example.

Sandy seemed to get people's attention in a way we haven't seen since the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf. It came in a year when the lower 48 states suffered the warmest temperatures and most disruptive weather patterns since such records have been kept. We're already spending billions in emergency aid for the victims of hurricanes and weather disasters; those numbers will only increase. In addition to Sandy, we had 10 other billion-dollar weather disasters in 2012, including Hurricane Isaac and terrible tornadoes across the Midwest and Great Plains.

I'm a member of an organization called the Planetary Society. If you haven't heard of us, we are a group of nerds who are deeply passionate about space exploration. We believe so deeply in the exploration of other worlds that we pay annual dues and organize fundraisers to pick up the slack left by governmental and commercial space programs. In addition to expansive efforts toward public education, we fund experimental approaches to space exploration and engineering. Spacecraft propelled by solar wind, or little robots that can move asteroids with laser beams are a couple of examples. Our CEO is Bill Nye. You may know him as "The Science Guy" from children's television.

Lately, Bill has been in the news cycle because of a video he made about creationism. In this video, Bill argues that the religions that teach stories of creation that oppose a contemporary scientific understanding are dangerous to public education. ... This puts me in an awkward position.

Editor's Note: Trevor Scott Barton wrote this poem after reading Subtle Is The Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein by Abraham Pais.

Einstein

experiencing a miracle

trembling with excitement

a compass

sparking genius

creating a world of thought

Euclidian Geometry in a small book

flying certainly away from the miraculous

finding the miraculous in clarity and certainty

gravity

Rydberg's Constant = 2π2em/h3c

landing uneasily in chaos

wandering and wondering in the quantum universe

God playing symphonies on strings

Quantum Theory is still in its relative infancy within the entire discipline of science, although it finds its roots as far back as Plato and Descartes. But if some of the notions being pursued by contemporary scientists prove true, it may result in a convergence of science, art, philosophy, and even religion that the world never imagined possible.

I’ll admit from the start that investigating the literature for this particular article literally made my head hurt. To fully conceive of all that is discussed and examined in Quantum Theory takes a scientific sophistication that I lack. But fortunately there are some out there who are trying to make these complex ideas more digestible, without a string of letters after our names.

One such scientist is Stuart Hameroff, Professor Emeritus at the Department of Anesthesiology and Psychology and the Director of the Center for Consciousness Studies at the University of Arizona. To distill a very complex idea down into a few words, the general consensus in science is that consciousness can be attributed to computations conducted within the neurological networks in the brain. Basically, all consciousness can be explained by algorithms, which makes our brains essentially like big, highly sophisticated computers. There are some limitations thus far to this perspective, such as how such algorithms account for things like aesthetic experience, love, and even our sense of smell. Researchers in the area of Artificial Intelligence believe that discovering the algorithmic bases for such phenomena can lead to the construction (given the necessary technology) of an artificial human brain.

Science students are known for their interpretive dance skills, right? Well, soon they might be.

For the last five years, Ph.D. students in science from all over the globe have been participating in Science's annual Dance Your Ph.D. contest.

The rules of Dance Your Ph.D. are simple:

- You must have a Ph.D., or be working on one as a Ph.D. student.

- Your Ph.D. must be in a science-related field.

- You must be part of the dance.

Imani walked down the hall with a paper cup in her hands.

She stopped and held up the cup to me. Inside of its paper walls were soil, water, and seeds — all those humble and elemental things that build a third-grader's scientific knowledge.

Imani was growing cabbage.

She was my student last year. She loved science and writing. I remember the look of wonder in her eyes when we studied weather. We learned about tornadoes. In my classroom, I had two 2-liter bottles connected by a tornado tube, a plastic piece that allows you to make a tornado by swirling the water around and around in one of the bottles. Imani held the bottles in her hands and marveled as her water formed into a giant, powerful funnel cloud.

"Wow," she whispered.

I love the sound of learning.

This is the third and final installment of my little series on Harry Emerson Fosdick, his sermons about Modernism and Science, and how these century-old sermons remind us that our present conversations about the same are anything but new. They may be necessary, but they aren't new. You can read my first post, “I Love How History Repeats Itself,” and my second post, “Science, Faith, and An Ongoing Conversation.”

I want to continue to focus on the same two sermons, "Shall the Fundamentalists Win?" and "The Church Must Go Beyond Modernism," and finish up a line of thought about American Christian Fundamentalism and interlace a third and final sermon entitled, “The Greatness of God” in which Fosdick outlines some of his own understandings of atheism, science, and religion. Typical of Fosdick, there is a tome hidden in between the lines of that sermon. Nevertheless, I'll try to share some of it with you.

What does Fosdick say is the trouble with Modernism? In “The Church Must Go Beyond Modernism,” he lists a few problems. Here's a list:

- “... it is primarily an adaptation, an adjustment, an accommodation of Christian faith to contemporary scientific thinking.”

- for this reason it tends “toward shallowness and transiency” and thus cannot adequately represent the Eternal;

- “Unless the church can go deeper and reach higher than that it will fail indeed.”

- “... excessively preoccupied with intellectualism” eschewing the heart and thus missing much of Christian spirituality

- excessive sentimentality, which means the eternal progress of the human character and the eradication of evil and the loss of moral judgment, scientific progress being equated with human moral progress

- “... modernism has even watered down and thinned out the central message and distinctive truth of religion, the reality of God.”

In a recent post here on God's Politics, Derek Flood suggested (as many have lately) that Christian communities need to start taking this whole "faith and science" thing seriously.

I posted some relatively snarky comment on my Facebook page about it (I apologize for the snark) suggesting that the authors of these recent posts about faith and science are ignoring about a century's worth of conversation and theology. Perhaps more.

Let me give you an example of what I mean in Harry Emerson Fosdick.***

As I said just yesterday, Fosdick was famous for lots of things, particularly the sermon "Shall The Fundamentalists Win?" which he preached on May 21, 1922.

It was a call to arms of sorts within the church, encouraging tolerance and a willingness to engage the minds of believers and unbelievers alike in a time of incredible scientific discovery.

I haven't written about the discovery of the Higgs Boson particle yet. I think I posted about it on Facebook or Pinterest or somewhere like that. I'm excited by the discovery. Actually, I'm excited by discovery in general. Discovery is good stewardship. This particular discovery is particularly intriguing (Get it? I used "particular" since we're talking about particles! I'm so clever in the morning.).

So, let me begin with a simple prayer. I want to get into this a bit.

God of the moon, God of the sun,

God of the globe, God of the stars,

God of the waters, the land, and the skies,

Who ordained to us the King of promise.

It was Mary fair who went upon her knee,

It was the King of life who went upon her lap,

Darkness and tears were set behind,

And the star of guidance went up early.

Illumed the land, illumed the world,

Illumed doldrum and current,

Grief was laid and joy was raised,

Music was set up with harp and pedal harp.

If you’re like me you probably haven’t been following the latest scientific discussions about Higgs Boson (a.k.a. “the God particle"). But today I came across a 7-minute video in which Daniel Whiteson, a physicist at the prestigious European research organization CERN, walks through what the particle means, what it is, how it can be found (if it can be found at all).

But the best part about the whole discussion is that it is animated! The folks at PhD comics “a grad student comic strip,” break down the entire talk with clever visuals and an engaging presentation style.

Thanks to Steve Knight for alerting me to this joke, which has become one of my instant favorites. After all, it combines two things I dig: nerd humor and theology (also nerdy).

Yeah, yeah, you may be groaning, but you’re smiling while doing it. Admit it.

There’s plenty of chatter lately about the so-called “God Particle,” recently discovered , with some in the scientific field actually calling it the “goddamn particle,” because (at least as I understand it) the discovery opens up the possibility of something without detectable mass actually giving mass to other particles.

Kind of like: In the beginning there was nothing, and then…

Sound familiar?

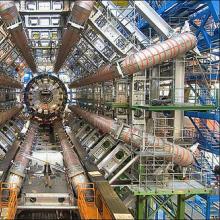

The Large Hadron Collider/ATLAS at CERN. Photo via Wylio (http://bit.ly/MpMJwS)

The Higgs boson is perhaps better known by its sexier nickname: the "God particle."

But in fact, many scientists, including the physicist for whom it is named, dislike the term.

In 1993 when American physicist Leon Lederman was writing a book on the Higgs boson, he dubbed it "the goddamn particle." An editor suggested "the God particle" instead.

One thing is clear: The July 4 discovery that marked a new chapter in scientific knowledge also reignited debate over the universe’s origins — and the validity of religious faith as scientific knowledge expands.

The Higgs boson explains why particles have mass — and in turn why we exist. Without the boson, the universe would have no physical matter, only energy.

The cosmological implications are hotly debated. Can God fit in a scientific story of creation?

According to the Atlantic Cities, lawmakers in North Carolina have chosen to ignore studies that show sea levels are rising faster than previously expected in favor of developing new housing along the coast.

According to the rerport, state Rep. Pat McElraft, a not-scientist, said in a floor debate that the state should assume sea levels will rise at the same rate they have in the past: 8 inches over the past century.

From Kelly Henderson's Switchboard blog post:

"The scientific findings that North Carolina coasts will likely experience a 39-inch sea-level rise created quite a stir and were challenged by NC-20, a coastal economic development group, who cited flaws in the research. The group fears losing dollars if coastal planning begins now to prepare for the 39-inch rise since over 2,000 coastal miles will become restricted to development."

And, from Mr. Colbert, on N.C.'s logic in only considering historical data:

"If we consider only historical data, I've been alive my entire life. Therefore, I always will be."

Sandi Villarreal is Associate Web Editor for Sojourners. Follow her on Twitter @Sandi.

Physicists answer the question "What is the Higgs-Boson?"

In 1964, the British physicist Peter Higgs wrote a landmark paper hypothesizing why elementary particles have mass. He predicted the existence of a three-dimensional "field" that permeates space and drags on everything that trudges through it. Some particles have more trouble traversing the field than others, and this corresponds to them being heavier. If the field — later dubbed the Higgs field — really exists, then Higgs said it must have a particle associated with it: the Higgs boson.

Fast forward 48 years: On Wednesday (July 4), physicists at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world's largest atom smasher in Geneva, Switzerland, announced they had discovered a Higgs-like particle at long last. If the new particle turns out to be the Higgs, it will confirm nearly five decades of particle physics theory, which incorporated the Higgs boson into the family of known particles and equations that describe them known as the Standard Model. (Source: LiveScience.com)

Still confused? (We are.) Inside the blog, four physicists explain on video.

The Dalai Lama is best known for his commitment to Tibetan autonomy from China and his message of spirituality, nonviolence and peace that has made him a best-selling author and a speaker who can pack entire arenas.

But somewhat under the radar screen, the Tibetan Buddhist leader and Nobel Prize laureate has also had an abiding interest in the intersection of science and religion.

That interest won Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, the 2012 Templeton Prize on Thursday (March 29), a $1.7 million award that is often described as the most prestigious award in religion.

"Galileo Galilei - Church of Santa Croce" via Wylio http://bit.ly/wpKD02

VATICAN CITY — Nearly four centuries after the Roman Catholic Church branded Galileo Galilei a heretic for positing that the sun was the center of the universe, the Vatican is co-hosting a major science exhibition in his hometown.

The Vatican is teaming with Italy's main physics research center to host "Stories from Another World. The Universe Inside and Outside of Us," in Pisa.

The exhibit will illustrate the progress of knowledge of the physical universe, from prehistoric times to recent discoveries. The exhibit is organized by the Specola Vaticana — the Vatican-supported observatory — and Italy's National Institute for Nuclear Physics, together with Pisa University's physics department.

The exhibition aims to tell "the history of the universe, from the particles which make up the atoms in our bodies to distant galaxies," the Rev. Jose Funes, director of the observatory, told reporters on Thursday (Feb. 2).