Power

"Living the Word" reflections for October 2014 can be found here.

ACROSS DENOMINATIONS, Christians have attempted to build a more egalitarian and democratic ecclesiastical structure. The phrase “discipleship of equals,” coined by the feminist theologian Elisabeth S. Fiorenza, suggests that a community of Jesus’ followers cannot tolerate an absolute, centralizing power that justifies a relationship of dominance and subordination.

Yet, while Christians continue to challenge hierarchical structures in the church, we also acknowledge that a discipleship of equals will not be established simply by removing the hierarchy. The church is enmeshed in a concrete reality of everyday life, filled with a web of power relations that are neither fixed nor necessarily top-down.

Power relations experienced within the church are often inconspicuous. They take the form of microaggressions, subtle insults against other members because of gender, sexual orientation, race, class, and ability status. What is even more hurtful is that these insults are often disguised as “caring,” as when someone perverts a prayer request into gossip. The experience of the powers in the church can be paradoxical. Christians must deal with complicated and variegated claims to power, all of which borrow the name of God.

The texts for the next four weeks highlight the struggles in forming a community of God. They raise the question of power relations within the faithful community: How do we use the word “power” and what should be our first instinct in situations of conflict?

WALTER WINK IS known as a lectionary commentator with lucid biblical insight, a chronicler of nonviolent practice, a scholarly essayist, an arrestee in direct action, and one of the most important theologians of the millennium’s turn. He effectively named “the domination system” and its collusive principalities, opened up biblical interpretation to an integrated worldview, and brought the New Testament language of power back on the map of Christian social ethics.

Two years ago he crossed over to God, joining the ancestors and saints. His first two posthumous books have now appeared. They make for good companion volumes. Let me weave back and forth between the two. Walter Wink: Collected Readings is the anthology of his core work. Just Jesus: My Struggle to Become Human is a short autobiography. The second is the more remarkable—because it’s so rare that a world-class scripture scholar should tell his or her own story in relation to encounters with the biblical witness. And all the more so because it was a project undertaken after he was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia.

Given the dementia, the book itself is an effort of his “struggle to become human.” An early version of the manuscript included oral history and other sources narratively adapted to a first-person voice, but in the end his partner in all things, June Keener Wink, pressed for it to be pure Walter. No words not his own. His voice is easily recognized in these pages, though not always in the familiar crafted and noted style, rich in quotable one-liners. The jewels are here all right, but this text feels simpler, sparer, plainer. There are prayers and memories of one suffering the weight and creep of memory loss. Though it is a book he conceived and set to writing, June (aided by a sainted editor) lovingly completed the sculpture with autobiographical pieces, journal entries, prayers, dreams, and important portions of his final magisterial work, The Human Being: Jesus and the Enigma of the Son of the Man. The latter, also well represented in Collected Readings, frames the struggle (Jesus’, Walter’s, and our own) to become human.

The news coverage of international conflicts can be very disappointing from a mimetic perspective. When conflicts escalate into violence as in Syria or the Ukraine, news outlets rush to cover the hostilities. They give us the facts on the ground, or rumors thereof, accompanied by an almost mindless report of what each side is saying by way of self-justification. However, if you listen to their rhetoric with mimetically tuned ears, which happens after spending time here at Raven, you realize that their rhetoric is all sound and fury signifying nothing. Unfortunately, it is this “nothing” that usually makes the headlines.

Major outlets like the New York Times rarely give as good an analysis as my colleague Adam Ericksen did last week. Speaking of the crisis in Ukraine, Adam said that we often think conflict is the result of differences. But the truth is that rivals resemble each other in often surprising ways. They are in conflict because they share the same desires and so are locked in a competition for something that they cannot or will not share. In the case of the conflict over Crimea, the “thing” is not the region but power and prestige. Adam explains:

Russia’s desire for power is mimetic, or imitative, and modeled on its rival for power, the United States. Russia wants what the United States has — the prestige of being a global super power — and Russia is willing to use the same methods that the United States has used to gain and sustain that prestige — violence.

Just as polar vortices sweep through America, Elsa, one of the main characters in the latest Disney princess movie, Frozen, unleashes her icy power in the fictional kingdom Arendelle, across theaters everywhere. In addition to delighting progressive audiences by satirizing Disney’s own trope of “marriage at first sight,” the story compels viewers, young and old, to find courage to be their true selves. The Oscar-nominated signature song, “Let It Go,” poignantly expresses the sentiment of letting go of fears, secret pains, and pretense. Fans of the song, from celebrities to little girls, have been belting the tune theatrically anywhere from kitchens to car rides to the Internet.

G.K. Chesterton says,

Fairy tales are more than true: not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.

A good story is more than a pleasurable experience — it empowers us to live a changed life. Frozen is filled with beloved characters and catchy melodies, but also has much to teach us about power, privilege, and community.

What a relief it would be to dwell in [faith] communities where we acknowledge our shadows in a healthy acceptance of ourselves as containers of all the opposites! It may prove beneficial to be forced to face, daily, the humiliating fact that some of us are no less violent than those whose policies we oppose.

—Walter Wink, Engaging the Powers

I AM A conscientious objector, and I am drawn to violence. My attraction to violence is both innate and learned. When something frightens me, my hands clench into fists. When something angers me, I want to inflict pain upon that thing. But a person cannot inflict pain upon a thing, so I seek out those whom I deem responsible for said thing and my desire to inflict pain upon a thing morphs into a desire to do violence to another person. Since I was a child, I have fantasized about using violence to stop what I see as bad and thereby become good.

It is from this point—from these fantasies of righteous violence—that I begin this essay on my journey to principled nonviolence and conscientious objection. This is a story of change and choice, but it is not a story of transformation: I am who I have always been.

In fall 2012, I spent three weeks in Israeli military prison for refusing to enlist in the Israel Defense Forces. (Every Israeli citizen, except for the ultra-Orthodox and Palestinian citizens of Israel, must serve in the military.) My sentence was brief, but the process that brought me to the prison’s gates took almost a decade.

IN TERMS, America has tried to heal itself. The Civil War took place in the 1860s. The civil rights movement took place in the 1960s. From America’s two biggest domestic conflicts emerge three main elements: the first, a group of people, primarily white, the majority and ruling group in society. Let’s call this group the “Land of the Free”; the second, also a group of people, but a minority, primarily black, originally from Africa, the “Other America”; and the third element of our simplified history is the slavery and poverty that divides the first group from the second and which we will call the “Wall.” ...

There are several questions I must ask myself if I am to be a Christian in America today. One that gives me a great sense of urgency is this: “If change only comes after confrontation and violence, what type of confrontation is needed to make the country livable for all people?”

Ah, Christmas! The most wonderful time of the year. A time to gather with family and friends, and, with a smile on our faces, pretend we aren’t quietly measuring who received the best present and which relative really, really needs to stop drinking. A time to hang tinsel and baubles from the tree, and a time to hang up our hopes of losing that last 10 pounds this year. Such a joyous season!

The real point here is that Christmas is what we make of it. For Christians, however, there are some very specific things you can’t do if you want to actually honor and follow the person we celebrate this season. So, I give you my “10 Things You Can’t Do AT CHRISTMAS While Following Jesus.” As with my other “10 Things” lists, this is not intended to be a complete list, but it is a pretty good start.

Two French soldiers died as a wave of deadly revenge attacks involving rival Christian and Muslim groups has left the Central African Republic in chaos.

But a Roman Catholic archbishop said the fighting pitting the two groups is not about religion, but rather politics and power.

“The religious leaders warned against this risk” of religious conflict, said Nestor Desire Nongo-Aziagbia of Bossangoa in a telephone interview. “Political leaders have not paid attention to these warnings. They wanted to antagonize the Central African Republic along religious lines in order to remain in power.”

IF YOU WANT to understand why the climate movement missed Tim DeChristopher when he was in jail for two years, you should read the letter he sent recently to the president of Harvard.

Drew Faust—Harvard’s first female president—had just spoken for the establishment (really, the establishment establishment) by publishing a weary, soulless letter explaining that Harvard would not divest from fossil fuels despite the request of 80 percent of its student body. DeChristopher—who was imprisoned for two years after an inspired act of civil disobedience to block a drilling lease auction in his home state of Utah—had just arrived in Cambridge to start at Harvard Divinity School.

“Drew Faust seeks a position of neutrality in a struggle where the powerful only ask that people like her remain neutral,” DeChristopher wrote. “She says that Harvard’s endowment shouldn’t take a political position, and yet it invests in an industry that spends countless millions on corrupting our political system. In a world of corporate personhood, if she doesn’t want that money to be political, she should put it under her mattress. She has clearly forgotten the words of Paolo Freire: ‘Washing one’s hands of the conflict between the powerful and powerless means to side with the powerful, not to remain neutral.’ Or as Howard Zinn put [it] succinctly, ‘You can’t be neutral on a moving train.’”

DeChristopher is exactly right. Just as a tie goes to the runner, so “neutrality” goes to the status quo. And given that we’re in a full-on climate emergency—the Arctic melted last summer, for crying out loud—this kind of neutrality is no more admirable than defending the right of poor and rich alike to sleep beneath bridges.

Fear sold the National Security Agency’s phenomenally intrusive program of spying on everyone and everything, but fear doesn’t explain it.

A nation reeling from terrorist attacks, the thinking went, would excuse the NSA’s vast eavesdropping on Americans and non-Americans, even friendly heads of state.

The reason for doing so, however, probably lay in something more mundane, more like the all-night party outside our apartment window last weekend.

Young men and women stood on a patio facing the courtyard of our U-shaped apartment building. They drank, and they talked. They drank more, and their talking turned to shouting.

By 4 a.m., their shouting and chugging were out of control. Who was going to stop them? No neighbor would dare knock on a door to confront drunks.

This was self-centeredness run amok. It was complete unawareness of consequences, complete disregard for the rights of others. An essential freedom to act had become a license to violate.

Sound familiar?

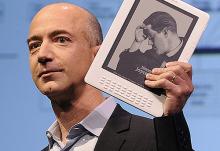

“I think it would be fun to run a newspaper.”

THE QUOTE IS from Charles Foster Kane, the character based on William Randolph Hearst in Orson Welles’ 1941 classic Citizen Kane. But it could have been Amazon kingpin Jeff Bezos this August when he bought The Washington Post. What can you get for the man who has everything? Maybe he’d like a newspaper to play with, preferably one with global political clout.

Unlike Charles Foster Kane or Rupert Murdoch, Bezos seems disinclined to monkey with the content of the Post’s coverage. His business interests may require certain government policy directions—i.e. free trade and no unions—but on those questions the Post is already with him. They differ on net neutrality (the concept that providers of internet access should not be able to discriminate against or give preference to specific internet service or content providers), so that will be one to watch. But Bezos comes to the Post saying he essentially agrees with the paper’s politics. In fact the Post’s reputation as a credible voice for corporate centrism seems to be a large part of what Bezos wants for his $250 million.

This may explain why Bezos, a titan of the rising digital world, would weigh himself down with an ancient “legacy” institution. It’s an old American story. When you get rich enough (Bezos’ fortune is estimated at $27 billion), you don’t want more money, you want power and respect. The same process played out with the robber barons in the last century. It’s just that today the evolution happens much faster. It took three generations for the Rockefellers to go from oil tycoons to philanthropists and politicians; contemporary barons such as Bezos and Bill Gates have made the switch within a couple of decades.

[Editor's note: This article first appeared in our December 2013 issue to commemorate the one year anniversary of the Sandy Hook shooting.]

IN THE YEAR since the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., last Dec. 14, thousands more have died by gun violence, and the NRA seems to stymie sane firearm measures at every turn. How do we stave off despair, hold on to hope, and keep moving forward when the odds feel overwhelming? —The Editors

Bigger Than Politics

What do we say to those who are weary?

by Brian Doyle

WHAT WOULD I SAY to those who are weary of assault rifles mowing down children of all ages, every few months, for as long as we can remember now? Oregon Colorado Wisconsin Pennsylvania Connecticut Texas Massachusetts Minnesota Virginia do I need to go on? I would say that this is bigger than politics. I would say this is about money. I would say Isn’t it interesting that we are the biggest weapons exporter on the planet? I would say that we lie when we say children are the most important things in our society. I would say that the next time a tall oily smarmy confident beautifully suited beautifully coiffed glowing candidate for office says the words family values, someone tosses an assault rifle on the stage with a small note attached to it that reads Is this more important than a kindergarten kid?

We all are Dawn and Mary in our hearts and why we wait until hell and horror are in front of us to unleash our glorious wild defiant courage is a mystery to me.

I would also say, quietly, that this is bigger than rage and anger and snarling at idiots who pretend to hide behind the Constitution. I would say this is also about poor twisted lonely lost bent young men no one paid attention to, no one really cared about. And I would say that people like Dawn Hochsprung and Mary Scherlach, who ran right at the bent twisted kid with the rifle in Newtown, are the flash of hope and genius here. Those are the people I will celebrate on Dec. 14. There are a lot of people like Dawn Hochsprung and Mary Scherlach, may they rest in peace. We all are Dawn and Mary in our hearts and why we wait until hell and horror are in front of us to unleash our glorious wild defiant courage is a mystery to me. But it’s there. And there are a lot of days when I think the whole essence of Christianity, the actual real no kidding reason the skinny Jewish man sparked the most stunning possible revolution in history, is to gently insistently relentlessly edge us away from our savagely violent past into a future where Dawn and Mary are who we are, and you visit guns in museums, and war is a joke, and defiant peace is what we say to each other all blessed day long.

Brian Doyle is the editor of Portland Magazine at the University of Portland (Oregon) and the author most recently of The Thorny Grace of It, a collection of spiritual essays.

-----

An Insanity of Rationality

This spiritual disease thrives on violence and calls it good.

by Joan Chittister, OSB

THERE IS A MADNESS abroad in the land, hiding behind the Constitution, brazenly ignoring the suffering of many who, over the years, have died in its defense, and operating under the banner of rationality. It’s a rare form of spiritual disease that thrives on violence and calls it good.

They want a proper response to violence, they tell us, and, most interesting of all, they insist that only violence can control violence. If “the good guys” have guns, this argument goes, “the bad guys” won’t be able to do any harm.

The hope? The hope lies only in those who refuse to feed this addiction to violence.

This particular insanity of rationality argues that violence is an antidote to violence. Then why do we find scant proof of that anywhere? Why, for instance, hasn’t it worked in Syria, we might ask. And where was the good of it in Iraq, the land of our own misadventures, where the weapons of mass destruction we went to disarm did not even exist and the people who died in the crossfire of that insanity had not harbored bin Laden. So how much peace through violencehave all the good guys on all sides really achieved?

The insanity of rationality says it is only reasonable to arm a population to defend itself against itself. And so, day after day, the level of violence rises around us as hunting rifles and small pistols turn into larger and larger weapons of our private little wars.

Clearly this particular piece of childish logic has yet to quell the gang violence in Chicago. It didn’t even work on an army base in Texas where, we must assume, the place was loaded with legal weapons.

What’s more, it does nothing to save the lives of the good guy’s children, who pick up the good guy’s guns at the age of 2 and 3 and 4 years old and turn them on the good guy fathers who own them.

So the mayhem only increases while white men in business suits insist that their civil rights have been impugned, their right to defend themselves has been taken from them, and more guns, larger guns, insanely damaging guns are the answer. Instead of hiring more police officers, they argue that arming students and teachers themselves, nonprofessionals, will do more to maintain calm and control the damage in situations specifically designed to cause chaos than waiting for security personnel would do.

It is that kind of creeping irrationality that threatens us all.

And in the end, it is a sad commentary on our society. We have now become the most violent country in the world while our industries collapse, our educational system declines, women are denied healthcare, our infrastructure is falling apart, and there’s more money to be made selling drugs in this country than in teaching school. No wonder gun pushers fear for their lives and sell the drug that promises the security it cannot possibly give while the country is becoming more desperate for peace and security by the day.

The hope? The hope lies only in those who refuse to feed this addiction to violence. These are they who remember again that we follow the one who said “Peter, put away your sword” when it was his own life that was at stake.

The hope is you and me. Or not.

Joan Chittister, OSB, a Sojourners contributing editor, is executive director of Benetvision, author of 47 books, and co-chair of the Global Peace Initiative of Women.

BECAUSE I'M A Jew in Bethlehem, Pa., also known as “Christmas City USA,” I spend December celebrating Jesus’ birth. Representations of other religions are largely absent, but with evergreen trees adorning lampposts, the nativity scene at city hall, and 6-foot-high electric Advent candles, Christmas here is both beautiful and unavoidable.

Given Christianity’s dominance in the United States, similar examples extend into other seasons and across the country. Christian holidays and Sunday receive scheduling deference, Christian worship options are varied and plentiful, and debates over public “religion” focus almost entirely on Christianity. In contrast, Jews use vacation days to observe holidays, Jewish religious communities are far fewer, and there is no movement advocating Jewish prayer in schools.

Even in interreligious settings intended to be neutral, Christianity retains primacy. Exchanges emphasize concepts in Christianity, such as belief and faith, and downplay the Jewish stress on action, behavior, and ritual. When interfaith interactions turn to biblical texts, they rely on Christian hermeneutical approaches such as using English translations without acknowledgment of their underlying Hebrew and eschewing the Jewish practice of viewing the Bible through subsequent commentaries. To me, these verses look discomfortingly naked when not swaddled with sages’ centuries-old wisdom, and Christian translations often conflict with how I understand the original language.

Violence against women is the most prevalent and the most hidden injustice in our world today. From rape as a weapon of war, to human trafficking, to the attack of a young girl seeking an education, the treatment of women and girls across the globe is in a state of crisis.

And we don't even need to leave our own shores to encounter staggering statistics. Here in the U.S., 1 in 5 women have been raped in their lifetime — a number that only jumps when you realize that 54 percent of sexual assaults are never reported. More than 1 in 3 women have experienced some kind of intimate partner violence. Sexual assaults in the U.S. military continue to rise — with an estimated 26,000 in 2012 alone — even as its leaders claim to be addressing the epidemic.

As I lay out in my book On God’s Side, what has been missing from this narrative is the condemnation of these behaviors from other men, especially men in positions of power, authority, and influence — like those in our pulpits. In a section of that book, I say we need to establish a firm principle: the abuse of women by men will no longer be tolerated by other men. The voices of more men need to join the chorus to make that perfectly clear.

It's time for all people of faith to be outraged.

THE SAGA OF Elijah that we are following in 1 and 2 Kings culminates in a poignant parting as the prophet prepares to be taken up into heaven. His disciple, Elisha, makes a final all-or-nothing request: “Please let me inherit a double share of your spirit” (2 Kings 2:9). Elijah states a condition for the fulfillment of Elisha’s prayer: “You have asked a hard thing; yet, if you see me as I am being taken from you, it will be granted you; if not, it will not” (2:10). It is as if Elisha has to look unblinkingly into the reality of their separation. If he is to inherit the prophetic mantle and spirit of his teacher, he must claim the vocation in its entirety. He is now to be the prophet.

The story is an uncanny pointer to the truth that John the Evangelist highlights in Jesus’ last words to his disciples: “I tell you the truth: It is to your advantage that I go away, for if I do not go away, the Advocate will not come to you ...” (16:7). John even echoes the “double spirit” theme in 14:12, when he has Jesus assure us that our prophetic endeavors will be more abundant and powerful than Jesus’ own!

The season following Pentecost helps us realize that we are the prophets now, vested with the mandate and endowed with the gifts for enacting the good news of liberation.

REV. SUSAN QUINN BRYAN walked into a meeting of the Friends of the Anna Louise Inn fully prepared for a room brimming with people. Instead, Bryan and the five other Presbyterian pastors she had brought with her doubled the meeting’s total attendance. Bryan was stupefied.

When she moved to Cincinnati in 2005 to pastor Mount Auburn Presbyterian Church, several of her congregants had taken her to the Anna Louise Inn, claiming it as one of the things they loved most about the city. And yet, in its time of need, hardly anyone had come to the Inn’s rescue. It would take several minutes before an even more startling realization came to Bryan.

“As [people] began talking, I thought, ‘Where’s the church? How can the church stand silent while this is happening?’” she said. “So I organized a breakfast and just sent out emails to all the clergy I could find.”

About 25 Cincinnati faith leaders came to Bryan’s breakfast, and out of it emerged an ecumenical force, crossing denominational divides to rally behind one of Cincinnati’s most revered institutions.

THE BATTLE FOR the Anna Louise Inn began in 2007 after Cincinnati Union Bethel (CUB), the social service agency that operates the Inn, decided the Inn needed updated facilities.

MY WIFE IS a pastor. Specifically, she’s the senior pastor of a prominent church in downtown Portland, Ore. I’m on staff too, but only part-time, and she enjoys telling people she’s my boss. Technically, I answer to the church board, but people get a laugh about the reversal of “typical roles.”

I get my share of “preacher’s wife” jokes, to which I have a handful of rote responses. No, I don’t knit or make casseroles. No, I don’t play in the bell choir. Generally, the jokes are pretty gentle, but they all point to the reality that few of us will actually talk about: We see the traditional roles of women as less important than those of their male counterparts. And so, to see a man who works from home most of the time and takes the kids to school while his wife has the “high power” job brings everything from the man’s masculinity to his ambition into question.

But regardless of the teasing I get, Amy has it a lot worse. One time, when she was guest preaching at a church in Colorado, a tall man who appeared to be in his 60s came up to her after worship. “That was pretty good,” he said, smiling but not extending his hand, “for a girl.”

Amy and I planted a church in southern Colorado 10 years ago, and we actually kind of enjoyed watching people’s expectations get turned on end when they met us. A newcomer would walk in the doors of the church and almost always walk up to me and start asking questions about our congregation.

“Oh, you’re looking for the person in charge,” I’d say. “She’s over there.” Then would come the dropped jaws and the wordless stammers as they reconfigure everything they assumed walking through the door. Amy’s even had people stand up and walk out in the middle of worship when they realize she’s about to preach.

WITH TROUBLING DIVORCE RATES, the trend among younger couples to postpone marriage or abstain from it altogether, and other factors, some feel we are in danger of losing marriage in this society. The institution is arguably in serious trouble.

This period of intense media focus on marriage—while more and more states legally affirm marriage equality and the Supreme Court ponders two related cases—offers the opportunity to examine the institution of marriage itself. How can we strengthen and support marriage, a critical foundation of a healthy society? How can we, as church and society, encourage the values of monogamy, fidelity, mutuality, loyalty, and commitment between couples?

A study by the Barna Research Group a few years ago found that “born again Christians are more likely than others to experience a divorce,” a fact that pollster George Barna said “raises questions regarding the effectiveness of how churches minister to families.” Our authors in this issue wrestle with what it takes to build long-lasting marriages, rooted in and offering a witness to God’s covenantal love. —The Editors

MY HUSBAND AND I have been married to each other for 42 years. Does this make me an expert on heterosexual marriage? Not really.

My experience over 40 years as a pastor, teacher, and theologian helps some in thinking about marriage, as I have counseled couples and performed countless weddings, in addition to my personal experience. But as a contextual theologian of liberation, I know that to extrapolate from your own experience, or even from that of a small group, means you end up colonizing other people’s experiences through ideological privilege. In short, what that means is you think you know more than you really do. Hence, using social, political, and economic analysis is crucial if we are to think theologically in context about marriage.

A couple of things seem clear, however. Marriage, in all its manifestations, is going through tremendous change in our society, and marriage as a social and political institution, and as a religious practice, needs strengthening.

COMING TO know Christ can be likened to culture shock, when all the old ego-props are knocked down and the rug pulled out from under one’s feet. A maturing relationship with God involves the pain of continual self-confrontation as well as the joy of self-fulfillment, continual dying and rising again, continual rebirth, the dialectic of judgment and grace. For the first time in my life, I have begun to have the strength to face myself as I am without excuse—but equally important, without guilt. I know that I am sinful, but I could not bear this knowledge if I did not also know that I am accepted.

I now understand the profundity of 1 Corinthians 13, when Paul says that all that ultimately matters is love. Human endeavor without it is a “noisy gong or clanging cymbal.” One may have “prophetic power” (i.e., be a perceptive theologian), “understand all mysteries and all knowledge” (i.e., be an insightful intellectual), “give away” all one has or “deliver” one’s “body to be burned” (i.e., be a dedicated revolutionary), “have all faith, enough to move mountains” (i.e., be an inspiring preacher). But without love these are nothing, absolutely nothing.

DREAMS CAN serve a powerful purpose. Jacob dreamed a ladder and was renamed Israel. Joseph dreamed the sun and moon and stars and was sold into slavery. The magi dreamed a warning and returned home by way of another road.

Years ago I had a dream. I sat, a child, on a dirt floor. Around me paced a horse, saddled, ready. In front stood an immense door, cathedral-tall and brooding. And though open, the space within was dark. I was holding a light. And in the dream, I knew we were to bring light into that darkness. And the darkness—the darkness was the church.

In Truth Speaks to Power: The Countercultural Nature of Scripture, Walter Brueggemann, professor emeritus of Old Testament at Columbia Theological Seminary, bears light to the exegetical (seminary lingo for interpretive) work and examination of the interplay between truth and power found in both familiar and less familiar narratives of Old Testament scripture. Rigorous in content, the read is nevertheless accessible to scholar and novice alike.

Brueggemann's concern with the interplay of truth and power rests on the observation that far too often truth, even biblical truth, is found colluding with and legitimizing the self-serving and self-preserving agenda of totalistic and monopolizing authorities. To use biblical imagery, truth sides with the Pharaohs and the Solomons of the world and not with those on its margins and periphery.

The first two chapters draw on Brueggemann's impressive scholarship of Old Testament text and narrative to paint a disconcerting picture where not only are the bad guys truly bad, the good guys aren't any better. Take Joseph, the Technicolor-dreamer-slave become all-powerful-vizier (think prime minister) of Egypt. It is Joseph's land acquisition scheme, strategically implemented amid drought and famine, that results in Pharaoh controlling most of Egypt's wealth. It is Joseph who creates a permanent peasant underclass—the very class that will cry out for liberation from the injustice of having to bake bricks with no straw. And Solomon—well, you know something's gone terribly amiss when your empire accumulates "six hundred sixty-six talents of gold" (1 Kings 10:14) each year. If you don't see the editorial subtext, write it out numerically. Ouch!