grief

You may know 別告訴她 by its English title: The Farewell.

The second feature film from director Lulu Wang stirred audiences with a story from Wang’s family. In the film, the main character, Billi, joins her family in China as they convene a wedding as an excuse to say goodbye to her grandmother, who has a terminal illness but does not know it.

At the wedding, the grief of imminent loss peeks through the haphazard nuptials. In some of the film’s most memorable moments, toasts take heartrending turns into breakdown, and a drinking game provides space to drown sorrows with alcohol and laughter.

In the game, Billi’s family is seated at a round table. Chanting in Chinese, one person repeats a phrase while flapping their arms like wings, then looks to another person, who takes over the chant. Whoever makes a mistake takes a shot. The general mechanics of the scene are clear, but unlike most of the film, there are no English subtitles.

I stopped praying for God to turn me into a boy after I found Rachel Held Evans and her work. I was convinced that God might love girls, but not so much women. In my world, there was little challenging the ideology that patriarchy was God’s good plan for us. Rachel was the first evangelical I knew who began to articulate any kind of challenge to that idea. Forming a digital community through her writing, she asked the hard questions that haunted thousands of us everywhere. She took a particular risk of faith many of us felt we could not, “the risk of birth” as she would later articulate while referencing Madeleine L'Engle's famous poem. Rachel’s writing and preaching over the years demonstrated a commitment to faith over unquestioning certainty.

We continually ask, as Christians, what it looks like to embody a Christ who is both risen and stoops down to rip his clothes in lament that things are not as they should be in this world. It is the Easter season, and yet, we mourn.

Each spring Lent is a season on the church calendar, beginning on Ash Wednesday and concluding on Easter, which prepares Christians for Easter. The believer prepares his or her heart to celebrate Christ’s resurrection by embracing practices of prayer and repentance. An important part of experiencing Lent is walking through lament.

O God, we grieve the hatred, the ugly, racist fear

that hurts our common living and harms those you hold dear.

For Muslims who were gathered to worship and to pray

soon found their lives were shattered as violence filled their day.

In an effort to help our family grieve the loss of our beloved Vickie Lee Jones, a preacher told us that it was God’s will that a white man named Gregory Alan Bush shot her to death in the parking lot of a Kroger grocery store outside of Louisville, Ky. because, as a witnesses implied, she was black.

It was not.

What could it possibly mean to us that an endangered species of orca whales hold a mourning period after losing their young? While mourning is a natural habit of many creatures, we should pay attention to Tahlequah’s process of grief. Perhaps if we observe the creatures we have been called to care for and learn from, we might learn something about what it means to be human.

THE ART OF ... book series from Graywolf Press focuses on writing craft and criticism. In each compact volume an accomplished writer takes on a single element or theme. The most recent entry in the series is The Art of Death, by Edwidge Danticat.

Danticat’s reflections on a wide variety of literature that wrestles with death—from Taiye Selasi’s debut novel, Ghana Must Go, to C.S. Lewis’ A Grief Observed—offer insights for readers as much as for writers. She explores the complicated emotional landscape of death and mourning, but also the myriad ways, tangled in questions of both justice and mercy, that death comes: accident, illness, deadly disasters, suicides, executions.

WALTRINA MIDDLETON'S VOICE lifts you to the highest highs with bellows of crisp spoken word. Seamlessly, her croons can plunge you down the rhythm of any blues-laced freedom song. Your heart is gripped with deep, rolling riffs of truth spoken.

Harnessing the power of pain is just one of her many spiritual gifts. Middleton is an ordained minister, activist, and artist with roots in the Gullah Geechee community in South Carolina. A self-professed country girl, she grew up in Hollywood, S.C., on the coastal Gullah Sea Island of Yonges, about 30 minutes outside of Charleston.

“It was beautiful—a swampland with dirt roads, farm, and fields,” she told Sojourners. “I made my grandparents’ hogs my pets before I realized they were actually dinner.”

It’s been a winding road on the path to self-discovery for Middleton, but she says music was there from the very beginning. “Music was central to our family,” she said. “It was an intergenerational medium that brought us together, but also rooted us in our faith.”

Her grandparents had 16 children, and all of them could sing or play an instrument. The family put together a group called the Middleton Gospel Singers that toured the local church community. “Part of the country circuit is to have some kind of gospel group,” she said. “The women in my family were the instrumentalists. I was always with my family when we would be in church all day going to these programs. The whole point was to worship God. It was just something that you did.”

Even when there wasn’t a church function or performance, Middleton says music was a part of her everyday life. “We had this big ol’ barn, and we would be in the barn sitting, rehearsing, and practicing,” she said. “Sometimes there would be a fire; sometimes people would just come, listen, and talk. While they were rehearsing, we would sit out there and eat crab.”

At these family gatherings, her artistic flair began to take shape. She admired her older cousins and says they heavily influenced her style. “They had this depth to them that I couldn’t describe,” she said. “It was very low and lamenting. I found myself trying to imitate their style. It also taught me that worship could also be lamenting.”

MICHAEL J. SHARP was a close friend of mine. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), he was a Mennonite witness, scholar, and peacemaker. Over the course of five years, first as a Mennonite Central Committee volunteer and then through the United Nations, Sharp cultivated relationships of trust amid dreadful violence. His work in the DRC included demobilizing armed groups, investigating human rights abuses, and reporting to the U.N. Security Council on “creating the conditions for peace” in the Great Lakes region of Africa.

On March 12, Sharp and colleague Zaida Catalan were killed while on a U.N. fact-finding mission in Congo’s central Kasai region. Earlier, they had documented five mass graves in the region. Over the months, the number had risen to 23. The bodies of Sharp and Catalan were found on March 27. The four Congolese members of their travel team remain missing.

Eastern Mennonite University, where Sharp attended as an undergrad, has an international program for peacemakers, with graduates such as Nobel Peace Prize winner Leymah Gebowee. Many return to their home countries to face political violence, torture, and death.

How do Christian peacemakers engage the loss of friends and colleagues? We train and study as hard for peace as soldiers do for war, yet we do not have to “soldier on” when one of us falls. We do not have to appear “strong for the cause”; there is no national myth that forces us to choke back our tears. Christian Peacemaker Teams, where I serve as executive director, immediately gave me leave to grieve and gather with loved ones. My colleagues and friends sat with our devastation. We did not pretend that the world made sense or that “God has everything under control.”

On Sept. 28, 6-year-old Jacob Hall was shot on the playground of Townville Elementary School in South Carolina. He died Oct. 1, after spending days on life support.

At his memorial service Oct. 5, Hall, who is said to have loved superheroes, was surrounded by superheroes of his own — family, friends, and classmates of Hall's arrived in capes and costumes to remember his life and to help reassure eachother that "the good will win," reports ABC News.

The West Nickel Mines School is long gone. Two of the survivors are now married. Several of the couples who lost their daughters have had more children.

The shooting 10 years ago in [Bart Township, Pa.] made headlines across the world as the Amish rushed to forgive the shooter. But the grief and pain live on.

On Oct. 2, 2006, a heavily armed milk truck driver, Charles Carl Roberts IV, burst into the West Nickel Mines School shortly after recess. By the time Roberts had committed suicide, less than an hour later, five girls aged 6-13 were dead, and five others severely wounded.

"Trust the deepest intuitions of your own heart, trust the source of your own truest gladness, trust the road, trust him. And praise him too. Praise him for all we leave behind us in our traveling. Praise him for all we lose that lightens our feet, for all that the long road of the years bears off like a river. Praise him for stillness in the wake of pain. But praise him too for the knowledge that what’s lost is nothing to what’s found, and that all the dark there ever was, set next to the light, would scarcely fill a cup."

Ta-Nehisi Coates on the Obama administration’s decision to seek the death penalty for the Charleston shooter: “The hammer of criminal justice is the preferred tool of a society that has run out of ideas.”

2. At Baylor, the Real Story Isn’t Hypocrisy. It’s the Victims of Sexual Assault.

“... this is a story much larger than Ken Starr and Baylor. This story is about power, and money, and institutions that claim to be faith-based but refuse to stand for victims and against violence.”

Lives in the hands of algorithms—

I arrange my Mondays around a certain ritual, a yoga class taught by my gifted teacher, Mireille (Mimi) Mears. She’s from Belgium. From Charleroi, to be exact. It's about 30 miles away from Brussels. Her nephew lives a few minutes away from the attack site with his wife and three children under the age of 6. Mimi always closes our class with a ritual, this prayer/meditation/homily (with her beautiful Belgian accent) and yesterday was no exception.

All of us are understandably sad about Paris — devastated. Many people have used striped profile pictures, candles, and flowers to express our collective solidarity. But in the wake of tragedy, almost half of the governors of the U.S. have responded with fear, announcing that they will do whatever they can to thwart the acceptance of Syrian refugees — from cutting funding for nonprofit resettlement agencies, to demanding religious screening tests.

If there’s one thing I learned from some of my friends who are refugees, it’s how to respond to grief. And there’s no one approach and they didn’t always get it right. But sometimes they did: Some refugees, in the shadow of shocking sadness, sang more than usual, prayed louder, invited more friends over for dinner, cooked their parent’s recipes. None of them responded with terrorism.

THE DEVIL HAS long been wildly popular on stage, dating back to the Middle Ages when church authorities routinely cancelled performances because they worried that representations of the devil were so deliciously tempting that weak believers might falter. The dualistic image of a good, sweet angel on one shoulder and dirty demon on the other has infiltrated popular culture from children’s cartoons to adult sitcoms, signifying the struggle of our tempted conscience. And the devil always has the better jokes. In literary works, such as Paradise Lost and Doctor Faustus, the devil’s presence has driven plots forward through acts of temptation, leading the protagonist into some lusty or murderous act. The cliché is brought to life: “The devil made me do it.”

In 2015, the devil makes a serious comeback on Broadway in a successful run of Robert Askins’ new play, Hand to God, nominated for five Tony Awards, including best play and best direction. Askins takes his audience on a different kind of devilish journey.

BIBLICAL LAMENT includes both pleas to God for help and mournful dirges. Sometimes they are rooted in individual travails and grief, other times in anguish for those crushed by injustice or war.

The psalmist and the prophets dig deep into visceral images of bodily suffering—and stretch up, out, yearning to find symbols and metaphors in nature that might capture the mercy and presence of a God who, the psalmist isn’t afraid to say, is sometimes a bit elusive.

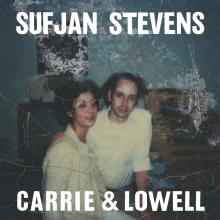

Sufjan Stevens’ newest album, Carrie & Lowell (out now), is a heartbreaking meditation on personal grief. It’s also joyful, baffling, and delicately mundane.

In the spirit of a listening party, a few of us sat down to play through the album, sharing liner notes and meditations on the songs that grabbed each of us. Conclusion: it's really, really good. Stream Carrie & Lowell here, and listen along with us below.

“Death With Dignity” — Tripp Hudgins, ethnomusicologist, Sojourners contributor, blogger at Anglobaptist

Tripp: I love the first song of an album. I think of it as the introduction to a possible new friend. “Where The Streets Have No Name” on U2’s Joshua Tree or “Signs of Life” on Pink Floyd’s Momentary Lapse of Reason, that first track can be the thesis statement to a sonic essay.

So, when I get a new album — even in this day of digital albums or collections of singles — a first track can make or break an album for me. I sat down and listened attentively to “Death With Dignity.” It does not disappoint. With it Stevens introduces the subject of the album — his grief around troubled relationship with his mother and her death — as well as the sonic palate he will use throughout the album.

Simple guitar work, layered voicing, and a little synth, the album is musically sparse. The tempo reminds me of movies from the nineteen sixties or seventies where the action takes place over a long road trip.

Catherine Woodiwiss: I was thinking road trip, too. There’s real motion musically, which, given a claustrophobic theme and circular lyrics, is a thankful point of release. It’s a generous act, or maybe an avoidant one — he could have made us sit tight and watch, and he doesn’t quite do it.

Julie Polter: This isn’t a road movie, but the reference to that era of films just made me think of Cat Stevens’ soundtrack for Harold and Maude, especially “Trouble.” (This album is one-by-one bringing back to me other gentle songs of death and duress and all the songs I listen to when I want to cry).

Director Jean-Marc Vallee (The Dallas Buyer’s Club) and writer Nick Hornby (author of High Fidelity and About a Boy) attempt valiantly to solve this problem, and achieve some moments of real beauty in the process. However, they never quite find a way to effectively connect Strayed (Reese Witherspoon) in her lowest moments, which include heroin addiction, the termination of a pregnancy, and divorce, with the woman we’re watching hike from Mexico to Canada — a woman who, while troubled, seems to have it considerably more together.

It also doesn’t help that the conversations Strayed does have on the trail tend towards the kind of dialogue that feels less like natural conversation and more like a talk between archetypes spouting bumper-sticker wisdom. The conversations that come up, about choices, regrets, and mistakes made, are all valuable. But the way they happen feels sanitized.

Ultimately, Wild does manage to present some solid thoughts on the process of grief and redemption. Strayed’s observation that everything in her life, both good and bad, led her to becoming a stronger, better person is important. Just as important is the film’s point that our relationships with others are vital to our survival and growth.

There’s no doubt that Strayed’s own experience was powerful and tough. But in its translation to film, particularly a film with a plot and performance tailor-made for awards season, Wild is a movie that’s afraid to upset people. It acknowledges the hard stuff, but barely hints at the true emotional complexities of its story and of its main character. Where it ought to challenge, it merely suggests. And while that’s okay, it’s disappointing that it isn’t more.