Grace

One sort of Christian believes taking Eucharist weekly saves her. Another Christian believes his confession of Jesus Christ as Lord saves him. Still another looks to his Baptism. Another to her participation in the body of Christ. One to his repentance. And another to her care for the sick, the hungry, the prisoner, and the poor.

We elevate one belief or practice over another, then divide ourselves as Christ followers by the priority we set when, in fact, all of these are taught as saving by Christ, who alone is our salvation.

Christ saves me, not the accuracy and purity of my beliefs. Christ saves me, not my works. Christ saves me, not the measure of my adherence to a doctrine or practice.

When all is said and done, many Christians tend to look to their habits, their faith, and their perseverance when it comes to salvation rather than to the work, belief, and faithfulness of Christ in us, over us, under us, and through us.

I was down in Mexico a few years ago for a gathering of peers who are leading faith communities around the world. It was a rich time of conversation, encouragement, and visioning.

Walking through a local Mexican neighborhood between sessions, something struck me. While those of us in the Minority World (often called the 1st or Western World) are thinking and talking about our theology, most of the folks in the Majority World (often called the 3rd World) have no choice but to simply live into their theology. Talking about our theology, faith, and practice in lecture halls, church buildings, and conference rooms is a luxury that the vast majority of Jesus followers in the world have no opportunity to participate in.

It’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it is reality. And those of us with this luxury better own up to it, because it is easy for us in the West to think we have a corner on the market of theology, which we then project (whether consciously or subconsciously) onto the rest of the world. But who's to say theology built in academia is any more valid than theology build in the realities of everyday life?

MANY PEOPLE HAVE been given a very tame and uninteresting version of Jesus. He was a nice, quiet, gentle, perhaps somewhat fragile guy on whose lap children liked to sit. He walked around in flowing robes in pastel colors, freshly washed and pressed, holding a small sheep in one arm and raising the other as if hailing a taxi. Or he was like an “x” or “n”—an abstract part of a mathematical equation, not important primarily because of what he said or how he lived, but only because he filled a role in a cosmic calculus of damnation and forgiveness.

The real Jesus was far more complex and interesting than any of these caricatures. And nowhere was he more defiant, subversive, courageous, and creative than when he took the language of fire and brimstone from his greatest critics and used it for a very different purpose.

The idea of hell entered Jewish thought rather late. In Jesus’ day, as in our own, more traditional Jews—especially those of the Sadducee party—had little to say about the afterlife, about miracles, about angels and the like. Their focus was on this life and on how to be good, just, and successful human beings within it. More liberal Jews—especially of the Pharisee party—had welcomed ideas on the afterlife from neighboring cultures and religions, especially the Persians.

To the north and east in Mesopotamia, people believed that the souls of the dead migrated to an underworld whose geography resembled an ancient walled city. Good and evil, high-born and lowly, all descended to this shadowy, scary, dark, inescapable realm. For the Egyptians to the south, the newly departed faced a ritual trial of judgment. Bad people who failed the test were then devoured by a crocodile-headed deity, and good people who passed the test settled in the land beyond the sunset.

Pope Francis is TIME's Person of the Year. But that is only because Jesus is his "Person of the Day" — every day.

Praises of the pope are flowing around the world, commentary on the pontiff leads all the news shows, and even late night television comedians are paying humorous homage. But a few of the journalists covering the pope are getting it right: Francis is just doing his job. The pope is meant to be a follower of Christ — the Vicar of Christ.

Isn’t it extraordinary how simply following Jesus can attract so much attention when you are the pope? Every day, millions of other faithful followers of Christ do the same thing. They often don’t attract attention, but they keep the world together.

Autumn in Berkeley is not what lovers of changing seasons might recognize as autumn, but it is upon us no less. Days are are shorter. Television programming has changed. The air is a little crisper. The currents in the Pacific have shifted and that great body of water tinkers with our meteorological hopes somewhat differently every day. The leaves don't change so much as drop. And, as usual, there are flowers in bloom.

As someone who loves the northeast coast change of seasons, I find it challenging to unravel my expectations from reality. I find the two so intertwined that I may be tempted to try to change my environment to suit my expectations rather than paying attention to what is actually going on in the world around me.

I am reminded of my neighbors who will be spraying fauxsnow on their windows to celebrate the winter holidays. "It's just not Christmas without snow," some will proclaim. This is an obvious example of what it may look like to insist on our expectations being met all the while our world around us is trying to show us something different. We literally paint the windows to the world around us so we see what we want to see.

We push our environment around and in the process run the risk of missing the grace being offered up in new and rich ways.

LEE DANIELS’ The Butler, a century-spanning tale of race in the United States and service in the White House, is a dream of a film—by turns historically realistic and magically fable-like. It’s a perfect companion piece to last year’s Django Unchained, in that case a movie whose tastelessness wrapped up as fabulous entertainment forced audiences to engage with a deeper level of the shadow of U.S. history.

Based on the story of Eugene Allen, a black man who served multiple presidents in a White House that took its own time to desegregate its economic policies for domestic staff, The Butler begins with a rape and a murder of plantation workers by the son of the boss. The ethical quality of the film is immediately apparent. This horror is not played for sentiment, nor even spectacle, but to evoke the very ordinariness of monstrosity.

This makes The Butler a rare film: one more interested in confronting us with a kind of previously unspoken truth than in goading us to feel the catharsis of guilt-salving by association. (It’s the antithesis of films such as Mississippi Burning, which use white protagonists to tell black stories and appear to believe that we can somehow participate in the virtue of the civil rights movement just by watching a movie about it.) The makers of The Butler have told a kind of truth about the struggle for “beloved community” that has rarely been seen so clearly on multiplex screens. The film illustrates the serious and painful work of nonviolence and invites us to consider the political and cultural tensions within the black freedom struggle, while giving a more humane perspective on the presidency than is often the case. We can hope the door is now open to more reflective cinema about the unfinished business of the black civil rights movement, broken relationships, traumatic memory, and how we tell the story of who we are.

The bearer of Good News, the one who carries the message of Resurrection, is not motivated by fear of punishment (either for herself or others) but by confidence in her experience of the love of God. She knows God's love is greater than anything in herself or in her hearers; that Jesus can conquer anything in them that is not controlled by holy love.

"Such love has no fear, because perfect love expels all fear. If we are afraid, it is for fear of punishment, and this shows that we have not fully experienced his perfect love." 1 John 4:18

God's love has the final word, for Jesus has conquered the sin of the whole world and has defeated the grave. Christ's best messengers know this love by its all-consuming redemptive activity in themselves and confidently carry this love to others, without fear.

This world is so beautiful

For no reason at all

When life circles around

And you can’t see straight

– from “Can’t See Straight” by Sam Phillips

"Push Any Button,” the first new physical album in five years from singer-songwriter Sam Phillips, is a blithe, fetching exploration of life’s flip side — after the flush of youth, after the heartbreak, after the bottom falls out and the road bends and you head in a wholly unexpected direction that turns out to be exactly where you need to be.

“Push Any Button,” which dropped Aug. 13, looks to the future by examining the past, viewing both through a lens of stubborn (and optimistic) grace.

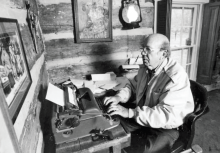

IN HIS EULOGY at Baptist pastor, civil rights activist, and author Will D. Campbell’s memorial service in late June, Campbell’s close friend, journalist John Egerton, recalled their first meeting. Campbell was wearing the broad-brimmed black hat that became his signature, with jeans and cowboy boots. At the time, Egerton noted, Campbell was in the middle of “a costume change” from the tweed jacket, clerical collar, and calabash pipe he had affected as a young, Yale-educated liberal minister.

Campbell was a notoriously theatrical figure, as famous for his hats and walking sticks as for his theological pronouncements. In fact, in the 1980s Campbell became a cartoon character in the guise of Rev. Will B. Dunn in the late Doug Marlette’s “Kudzu.” Campbell also dramatized his own life in Brother to a Dragonfly, his National Book Award-nominated 1977 memoir, and in a 1986 sequel, Forty Acres and a Goat.

Another favorite prop in the Will Campbell show was the acoustic guitar he would strum while singing his own country compositions and old favorites like “Rednecks, White Socks, and Blue Ribbon Beer.” Campbell, who was based in Nashville from 1957 on, also became a sort of chaplain to the “outlaw” element in that city’s country music industry. He traveled on Waylon Jennings’ tour bus, and Jennings’ widow, country star Jessi Colter, sang at Campbell’s memorial.

When the Pharisees heard that [Jesus] had silenced the Sadducees, they gathered together, and one of them, a lawyer, asked him a question to test him. “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” He said to him, “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” —Matthew 22:34-40

FAITHFUL PEOPLE are often stubborn people. Cambodian Buddhists are no exception. Truth-seekers in Cambodia sometimes spend a year living as beggars. They walk from village to village, trying to avoid the millions of remaining land mines. Their only possessions are a bright orange robe and a beggar’s bowl. After the ravages of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge regime, which dismantled community trust one forced-labor camp at a time, one might think the Buddhists would write off this ancient tradition, for no other reason than that it is grounded in the blind trust of perfect strangers. But faith, as Jesus taught, needn’t be any larger than a mustard seed. No regime, regardless how brutal, can eradicate faith.

This Cambodian Buddhist tradition of giving your entire well-being over to a community of strangers is one that has something to say to those of Christian faith. Giving yourself over to poverty, over to those who don’t know you from Adam, must change a person. After spending a year as an intentional beggar, as theologian Barbara Brown Taylor notes, you’d be hard pressed to differentiate yourself from all those “others” we tend to pity, fear, admire, or despise.

Rather than a Third Great Awakening I believe we are standing in the threshold of a Great Grace Awakening. It’s a move of the Holy Spirit drawing people away from legalistic and fear-based beliefs to a place some of us would call grace.

On the surface, it may seem to fly in the face of some traditional Judeo-Christian ethics. But it is aligned with a broader, more universal ethic that seems to be developing around genuine Christian love and grace — the very essence of Jesus’ ministry and what makes it so revolutionary — as guiding principles.

Grace is the reason for the incarnation. God became human and walked in our sandals because God knows us and wants us to be known.

Grace says that there is nothing we could ever do that would make God love us less. And grace tells us that there’s nothing we could ever do that would make God love us more. You are loved simply because you are and for all of who you are. Full stop.

More than 1,200 people have signed an online petition decrying the “silence” and “inattention” of evangelical leaders to sexual abuse in their churches.

The statement was prompted by recent child abuse allegations against Sovereign Grace Ministries, an umbrella group of 80 Reformed evangelical churches based in Louisville, Ky.

“Recent allegations of sexual abuse and cover-up within a well known international ministry and subsequent public statements by several evangelical leaders have angered and distressed many, both inside and outside of the Church,” reads the three-page statement spearheaded by GRACE (Godly Response to Abuse in the Christian Environment).

“These events expose the troubling reality that, far too often, the Church’s instincts are no different than from those of many other institutions, responding to such allegations by moving to protect her structures rather than her children.”

Simple Truths

The Live Simply series, a set of four booklets based on the values of St. Francis of Assisi, is packed with practical, portable advice about ethical eating, holistic health, creation care, and sensible shopping. Ideal for anyone seeking a life of simplicity and satisfaction in a world of consumption. Franciscan Media

Lost and Found?

A decomposing body is found in the Sonoran Desert, with a tattoo, “Dayani Cristal.” The documentary Who is Dayani Cristal? shows the efforts to find out who this mysterious migrant was and the journey he likely followed. A haunting look at the people affected by the politics of immigration. www.whoisdayanicristal.com

Go Here to read the second in this series, Competing for the Greater Good

Peru is a land of extremes, especially for a motorcycle pilgrimage. Our journey from Lima to the orphanage in Moquegua took us through some of the most severe riding conditions imaginable. Storms of Peru, the second segment in the Neale Bayly Rides series, provided a glimpse into the challenges we faced, as Peru would not give up her beauty easily.

Our ride began in the congested, chaotic streets of Lima — a thriving metropolis of 16 million people — where an aggressive riding posture is your only chance for survival. It’s not that the Peruvians are bad drivers; it’s just that traffic laws don’t seem to be a concern for any of them. Riding through the boiling cauldron of cars felt like a massive vehicular free-for-all. Lima provided a baptism by fire for our adventure and, exciting though it was, we were glad to leave the haphazard traffic behind us.

We rode south toward the beautiful but haunting desert of Ica. The life-smothering heat and blowing sands sweep across the land and stop abruptly at the Pacific Ocean. Riding through the rugged terrain of crushed rock, sugar sand, and loose gravel was even more challenging than it appeared on television. I was glad the production team didn’t show everything. I bit the dust more times than I care to admit.

The country is amazingly beautiful, as are the people. There's a crazy juxtaposition of things you have to see to believe — poverty mixed with joy, beauty and brokenness in the very same face, a fierce gratitude in the meanest of circumstances.

THE FUNCTION of healthy religion and church is to provide individuals and society with a collective container that carries the objective truth of reality for individuals. The Great Truth is too grand and transcultural to be entrusted to the vagaries of individuals and epochs. Otherwise, society becomes a massive runway for unidentifiable flying objects—each claiming absolute validity and turning their subjectivity into the only sacred.

The ground for a common civilization and shared values is destroyed if our religious experience is basically unshareable or without coherent meaning. We end up where we are today: pluralism without purpose, individuation but no community.

LAUGHTER IS Sacred Space: The Not-So-Typical Journey of a Mennonite Actor has the narrative arc of a classic Greek tragedy: Boy from religious sect grows up, becomes a butcher, goes to seminary, then finds acting acclaim as part of a duo (Ted & Lee), only to have his comedic partner die by suicide, after which the show must go on and does.

Ted Swartz’s story is a bittersweet tale, with emphasis on the sweet. It is told in the structure of a five-act play. What originally drew me was the fact that Swartz’s late acting partner, Lee Eshleman, was a classmate of mine at Eastern Mennonite University, where we were art majors to-gether. Eshleman was easily the most talented among us. (His line drawings illustrate the book.) He was also smart, funny, and regal.

After I left EMU, unmarried and pregnant, I would sometimes see Eshleman’s name on the masthead of the alumni magazine and think, “I wish I had it as together as Lee does.” It was a shock to hear that, like my own son, Eshleman too had died by suicide.

His death and its impact on Swartz take up a good deal of space in this memoir. The duo worked together for 20 years, and Swartz is honest about the ups and downs of their friendship. He does a great job of communicating that Eshleman was much more than his suicide or his bipolar disorder. He was that extraordinary person I remember.

COMING TO know Christ can be likened to culture shock, when all the old ego-props are knocked down and the rug pulled out from under one’s feet. A maturing relationship with God involves the pain of continual self-confrontation as well as the joy of self-fulfillment, continual dying and rising again, continual rebirth, the dialectic of judgment and grace. For the first time in my life, I have begun to have the strength to face myself as I am without excuse—but equally important, without guilt. I know that I am sinful, but I could not bear this knowledge if I did not also know that I am accepted.

I now understand the profundity of 1 Corinthians 13, when Paul says that all that ultimately matters is love. Human endeavor without it is a “noisy gong or clanging cymbal.” One may have “prophetic power” (i.e., be a perceptive theologian), “understand all mysteries and all knowledge” (i.e., be an insightful intellectual), “give away” all one has or “deliver” one’s “body to be burned” (i.e., be a dedicated revolutionary), “have all faith, enough to move mountains” (i.e., be an inspiring preacher). But without love these are nothing, absolutely nothing.

I am tormented by what took place at the Boston Marathon. An iconic event that is supposed to be a celebration of achievement and companionship will be scarred with memories of injury and death for years to come. However, the source of my distress is not only the horrific sights and sounds of violence and terror, but in such dreadful disasters I also struggle with our common conceptions of a loving God. As many wonder where God was in the midst of such tragedy, and while others question why God did not (or could not) prevent such terror from taking place, I am personally tormented with my belief of where God's love will be placed in its aftermath.

On the one hand, we are told “blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted” (Matthew 5: 4), and in receiving the Gospel in such ways, we take comfort in the belief that God is with those who suffer and directly at the side of those who struggle. This conception of a loving God offers relief for the victims in Boston and all those on the receiving end of transgression. However, while we proclaim a God in solidarity alongside those in pain, we are also often told that God is present with those who cause the pain, for the love and forgiveness found in Jesus is inclusive, it has no boundaries, and nothing is able to “separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Romans 8:38-39). So just as Jesus was sent to soothe those who suffer, he also absolves those responsible for the suffering. As a result, we are left with a God who seems to love both saints and sinners, which means we are both comforted and confronted in the aftermath of tragedy in Boston.

I try to be a diplomat, to err on the side of patience, when it comes to theological differences between Christians.

Reconciliation and peacemaking come natural. My wife says I stop sounding like myself when I'm hard-nosed or critical.

But recently, sitting across from a young man who heroin ("that boy") very nearly got the better of just days before, I lost at least a layer of my irenic self, lost a bit of my cool. When it comes to certain teachings, I'll not be as diplomatic in the future.

When are we going to stop teaching that the Father has to look on Jesus to love us? Why do we teach that the Father turns away from us, abandons us because of our sin? When are we going to stop teaching that the Father is angry with men and women or hates us (or stop projecting any other merely human emotion on to God?), conveying by our messages (verbal and nonverbal) that God despises that which he gloriously made in God's image?

The message we too often send is that Jesus must persuade the Father to love us, must plead with his Father not to forsake us.

HOW SHALL WE engage with scripture through all 50 days of Easter? There are clues in the haunting story of Jesus' appearance beside the sea of Tiberius. After Easter Day many of us are ready to let things quickly revert to normal. It is, strangely, both reassuring and uncomfortable to hear that those disciples, whose business had been fishing, wanted to get back to their boats so promptly after the horrors and wonders they had witnessed in Jerusalem.

Jesus is waiting for them by the shore with breakfast already cooking. All is ready, yet he wants them to bring some of what they haul up in their nets, so he can include samples of their own catch in the menu. And what a catch it was!

Easter is our time to experience the grace that is always ahead of our game and is underway for us before we are ready. Yet grace does not exclude what we bring to the table. Grace expects and includes the work of our hands, the weavings of our imaginations, and the gifts of our unique experiences. In one sense, Eastertide is more truly a season of repentance than is Lent. One thing we might need to repent of is our passivity—those times when we expect God to hand us on a plate the meaning we are hungry for. We need to bring our own bits to the cooking fire if we are to really eat with Jesus. It is part of the mix of grace that we must participate, not just receive.