Economics

During the most consequential ceremonial week in the Christian liturgical year, Holy Week, one of the most iconic Christian structures was reduced to an unholy sight. For hours, we could not look away as flames marching toward the sky swallowed an 800-year-old reminder of France’s Catholic story. A week after the world-jolting fire ravaged Notre Dame de Paris, the restoration fund now boasts more than $1 billion in pledges.

Many people, both inside and outside of the church, spoke about the problem of child care according to the same reasons. They viewed it as a complex, local problem with complex, local solutions. A team of parents attempted to create a new center and soon discovered the massive amount of capital, time, energy, and attention it would take. Everyone involved insisted that some solution must be possible if only we could bring together various stakeholders in the community to find a way to provide child care for those that need it. But this obscures the truth about the problem of child care in capitalism: It’s not complex and local, but big and universal.

In Redeeming Capitalism, Kenneth J. Barnes argues that the moral failures of our economy are evidence of moral decay in our social institutions. The greed and excess of Wall Street and the vast income inequality between the very wealthy and everyone else demonstrate that the moral fabric of our society is in tatters. What we need, Barnes believes, is a lesson in virtue. Barnes, I think, would like to replace Falwell Jr.’s ethic with a truly Christian one. If we want a virtuous capitalism, he argues, we need virtuous people.

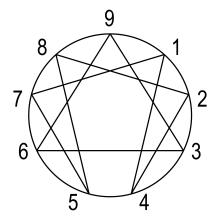

One reason the Enneagram works well within the capitalist system of work is its intense focus on individuals. The Enneagram reduces arguments of substance to those of procedure, but not typical formal procedure like raising a motion in a meeting according to Robert’s Rules of Order, but emotional procedure based on how each person involved in the argument feels, hears, and understands the substance of what’s being discussed.

It is possible to have a life without healthcare co-pays, deductibles, and premiums. It is possible to live in a country where we no longer watch our neighbors and loved ones suffer and even die because they cannot afford the care they need and deserve. And now we have an academically and economically rigorous study that proves it.

“Socialism” is increasingly losing its status as a dirty word in the United States, especially among young people. A Gallup poll from this year reports an increase in positive attitudes toward socialism and a decline in positive attitudes toward capitalism from Americans aged 18-29, consistent with other polling trends from previous years. Though there is no shortage of Christians wringing their hands over the changing political landscape, Christians have also shown up at strikes, campaigned for candidates endorsed by socialists, and joined socialist organizations.

There are many faithful Christians who have worked for radical change in the belly of the world’s wealthiest nation long before the 2016 primaries. Their experience brings lessons and context for today’s budding movements. One of these Christians is Sister Kathleen Schultz, a Roman Catholic sister who served as the National Executive Secretary of Christians for Socialism (CFS) in the U.S. for almost a decade. At 76 years old, she remains a thorn in the side of the powerful.

We are told that the world has never been richer, freer, or more advanced but at the same time, there are many who don’t seem to feel this. Among the young, especially, anxiety and depression seem rampant and young people are held up as politically disillusioned, increasingly turning their back on both political processes and institutional religion. How might this relate to neoliberalism? And what does neoliberalism have to with theology?

“How can we afford it?” That’s the perennial question that confronts anyone who dares to propose progressive policy changes. A recent example is CNN’s Jake Tapper grilling congressional candidate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez over whether tax money could fund items on her platform such as Medicare for all, a federal job guarantee, and cancelation of student loan debt. For those who are religious and politically progressive, this question is particularly challenging. While many are good at articulating the moral imperative of providing health care to all or protecting the environment, they can stumble on the issue of economic feasibility. So, when I was told about an economics conference in New York City that might connect to this topic, I was intrigued.

The rift between rich and poor runs deeply through the Asian American and Pacific Islander community. A recent Pew study reveals that Asians, as a whole, “rank as the highest earning racial and ethnic group in the U.S.” But the top 10 percent of AAPI persons earn 10.7 times the amount of those in the bottom 10 percent.

The city of Antioch — in modern-day Turkey — was beautiful and bustling in the fourth century. Various emperors and wealthy patrons donated money to build a colonnaded street through the middle of town. Well-to-do citizens decorated their marble halls with colorful frescoes and statues. They demonstrated their wealth by plating their walls and rooftops with gold. Even the city’s cathedral was called the “Golden House.” It would eventually seat a Patriarch, John, nicknamed “Chrysostom” or “Golden Mouth.”

Viking Economics: How the Scandinavians Got it Right — And How We Can, Too, by George Lakey. Melville House.

“I am sure the largest currency used on the black market, for [buying] haram things, is the U.S. dollar. So if the question of a currency being haram is what it is used for, the dollar would be the most haram,” Sabree said. “Just because a tool is used for something haram, doesn’t mean the tool is haram.”

A common misconception is that to be a pro-life Catholic, one simply has to be anti-abortion and anti-contraception. For years this “pro-life” definition has largely been unchallenged. That is, until recently.

A poll conducted in 2014 by the Public Religion Research Institute found a majority U.S. Catholics favor greater government involvement on economic issues via minimum wage increases, infrastructure investments, and universal healthcare. Furthermore, U.S. Catholics believe that to promote economic growth, the government should raise taxes. These aren’t just pro-growth policies, they’re pro-life policies.

Thanks to an invite from the Vatican, Bernie Sanders will leave the campaign trail after his April 14 debate with Hillary Clinton, and fly to Rome for an event the next day at the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.

He will gather with other world leaders to discuss changes in politics, economics, and culture in the light of Pope Francis' new encylical Laudato si', according to a statement released from the Pontifical Academy .

AN UNUSUAL TITLE recently caught my eye at the library. The book is called The Moral Molecule: How Trust Works, by Paul J. Zak. An economist with obvious interests in biology, psychology, and religion, Zak’s numerous experiments demonstrate that when someone is shown a sign of trust or when one’s empathy is engaged, a certain molecule called oxytocin surges in the brain and blood.

“When oxytocin surges,” says Zak, “people behave in ways that are kinder, more generous, more cooperative, and more caring.” In other words, they follow the Golden Rule of treating others as you want to be treated. Zak eventually demonstrates how oxytocin can work within economic systems, which reminded me of a children’s song we sang at a church I used to attend in Chicago: “Love is like a magic penny. Hold it tight and you won’t have any. Lend it, spend it, and you’ll have so many they’ll fall all over the floor!”

And that reminded me of research I had done on the early Jerusalem church in the book of Acts. If there ever were oxytocin surges, it must have been at Pentecost and in the days and years of the shared economic community that followed!

Two summary texts describe the common life shared among these earliest believers: Acts 2:44-47 and 4:32-37. The first tells of their daily life together, distributing possessions, worshiping in the temple, and eating a daily communal meal in various households. The second passage describes the renunciation of private ownership. Believers sold their land and homes and gave the money to the community to be distributed “as any had need” (4:35).

Why did they do this? Wasn’t it impractical and more trouble than it was worth? Didn’t they soon have to cope with cheaters like Ananias and Sapphira (5:1-11) or complaints from Hellenist widows (6:1-6)? Didn’t that radical idealism soon peter out and people go back to their former lifestyles?

Interpreting through middle-class mirrors

My research on how these economic texts have been interpreted throughout Christian history was eye-opening. Ever since market capitalism arose in the 14th century, many commentators considered the communalism of the Jerusalem church to be unrealistic. For example, John Calvin, a 16th century community organizer, writes in his Acts commentary that he had to “properly” interpret communal sharing in 2:44 “on account of fanatical spirits who devise a koinonia of goods where all civil order is overturned.” He especially criticizes the Anabaptists of the time, because “they thought there was no church unless all mens’ (sic) goods were heaped up together, and everyone took therefrom as they chose.” Instead, Calvin recommends that “common sharing ... must be held in check.”

The rise of historical criticism during the 19th century in the West led to much skepticism about the accuracy of biblical texts. Luke wrote decades later, scholars asserted, idealizing the early church in Acts. The Jerusalem believers were very poor and had to help each other out, so Luke turns this grim picture into a Golden Age of sharing. In his 1854 commentary, Edward Zeller maintained that Acts 1 to 7 was full of legends and fictitious stories that Luke himself created.

The conservative reaction to such skepticism was to affirm the historicity of the early chapters of Acts—but to see this as a socialist experiment that soon failed and was never tried again. Its failure was confirmed by the poverty of the Jerusalem church in Acts 11:27-29, where the disciples at Antioch decided to “send relief to the believers living in Judea.”

No doubt these notions about the community of goods in Acts 2 to 6 prevail in many churches today. But both perspectives get it wrong because scholars and laypersons alike read these texts out of their own economic situation—Western capitalism. For middle and upper-middle classes (from which most biblical scholars emerge), capitalism has worked well. As a political and economic system, it has staunchly opposed Marxist and other ideas of socialist communalism, often perceived as “godless.”

This hostility has made it almost impossible to view the socialism of the early Jerusalem church as a positive development or one that survived more than a few years. For example, G.T. Stokes’ 1903 Acts commentary in the English Expositor’s Bible series declared that the Jerusalem experiment was a socio-economic disaster that should never have happened. One of the evils it produced, according to Stokes, was the conflict between the Hellenist and Hebrew widows in Acts 6:1. Stokes assumes they were destitute widows fighting over poor relief. Reflecting Victorian class distinctions and paternalistic attitudes, he asserts, “No classes are more suspicious and more quarrelsome than those who are in receipt of such assistance ... Managers of almshouses, asylums, and workhouses know this ... and ofttimes make bitter acquaintance with that evil spirit which burst forth even in the mother church of Jerusalem.”

Only seven contenders will be on the main stage for Fox Business News’ broadcast of the sixth GOP 2016 presidential debate Jan. 14 — almost all well-known for taking strong stands on faith in hopes for a boost from devoted viewers. The December debate was the third-most-watched one in debate tracking history, according to CNN. The theme of this week’s debate will be economic policy, with managing editor for business news Neil Cavuto and global markets editor Maria Bartiromo asking questions.

WE NEED TO overthrow...this rotten, decadent, putrid industrial capitalist system.”

So wrote Dorothy Day, the Catholic Worker co-founder whom Pope Francis recently held up to the U.S. Congress as a great exemplar of the American spirit.

In the centuries since the rise of capitalism, millions of Christians, like Day, have sought not only to bind up the wounds of the poor, but also to create a world in which people will not be impoverished by low wages, unemployment, discrimination, or plain bad luck. Day ended up advocating a sort of communitarian anarchism. But for many other Christians—from Mother Jones to Dom Hélder Câmara to Martin Luther King Jr.—the name for that alternate system has been “socialism.” And, after long decades during which acceptance of the existing economic order seemed inevitable, in 2016 the question of socialism is not only on the agenda again but, in the Democratic presidential primaries, on the ballot.

This is especially surprising because any alternative to corporate capitalism was widely declared dead after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, which had called itself a socialist state and imposed its rule by force. Its failure, in the end largely economic, was rightly seen to discredit the Marxist-Leninist version of socialism that relied on centralized, coercive state power to manage the lives of its citizens. In the wake of the collapse, the West flooded the formerly communist states with free-market economic gurus to guide a sort of capitalist extreme makeover, and the end of history was declared.

But then global capitalism had its own collapse in 2008. In the U.S., the dream of upward mobility is dying. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, since 1973 the inflation-adjusted average hourly earnings for workers with a high school degree or less have declined; more-educated workers have barely stayed even. Meanwhile, according to the Economic Policy Institute, the inflation-adjusted income of the top 1 percent has risen 138 percent since 1979. A generation has arisen that sees its prospects declining. For this generation, “socialism” has little to do with the Soviet Union; it’s just another insult that Fox News hurls at the president most of them supported.

So for the first time in 100 years, a democratic socialist, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, is waging a serious U.S. presidential campaign. Since his campaign began, the percentage of Americans who say they are willing to vote for a socialist has risen. In fact, for the past five years, U.S. public opinion polls have shown increasingly favorable associations with the word “socialism.” Among millennials, the S-word’s positives are now higher than its negatives.

Even in the Catholic Church, consideration of socialist alternatives no longer seems taboo. Since the days of Pope John Paul II, liberation theology has been on the outs in Rome, but last year Gustavo Gutierrez, who gave the movement its name with his 1971 book, A Theology of Liberation, was welcomed to the Vatican to address a conference. This is the same man who famously proclaimed that Christian theology needs to speak “of social revolution, not reform; of liberation, not development; of socialism, not modernization of the prevailing system.”

The Rev. Martin Schlag is a trained economist as well as a Catholic moral theologian, and when he first read some of Pope Francis’ powerful critiques of the current free market system he had the same thought a lot of Americans did: “Just horrible.”

But at a meeting on May 11 at the Harvard Club, Schlag, an Austrian-born priest who teaches economics at an Opus Dei-run university in Rome, reassured a group of Catholics, many from the world of business and finance, that Francis’ views on capitalism aren’t actually as bad as he feared.

The papal address to the Republican-controlled Congress is likely to be one of the most closely watched talks during the pope’s weeklong visit to Washington, New York, and Philadelphia this fall, especially since the presidential campaign season will be growing more intense.

Francis isn’t shy about tackling controversial topics or upending conventional orthodoxies about Catholics and politics — a prospect that makes U.S. conservatives especially nervous, given Francis’ insistence on raising concerns about issues such as economic justice, climate change, and immigration.

DESPITE APPEARANCES, economics is in essence a very personal and fundamentally moral discipline. It is nothing short of the web of our material relationships with one another and with the natural environment. Economic relationships have personalities and personal histories. Inescapably, these relationships physically manifest our social and spiritual values.

Our language expresses this duality. “Values” are both moral principles and economic measures. “Equity” is defined both as a financial interest in property and as fairness or justice. The root of “property” is also the root of “propriety.” But perception and practice often reflect a division between them.