Economic Justice

Baseball players Larry Doby was black and Steve Gromek was white. Gromek was from the working-class culture of Hamtramck, Mich., and Doby from the Jim Crow culture of Camden, S.C.

One year earlier, on July 5, 1947, at Comiskey Park in Chicago, Doby had become the second African-American behind the great Jackie Robinson of the immortal Brooklyn Dodgers to play for a major league baseball team and the first African-American to play in the American League.

It was a revolutionary picture because it showed the world a way white supremacy and racism could be overcome.

Ask a random group of people, “How do we improve our public schools?” and you’re apt to get divergent, passionate answers. Christians, like other citizens, have different opinions on how to heal what’s hurting in our education system. What we can share is a belief that all children are truly precious in God’s sight and an understanding that public education is a key component of the common good—that a healthy school system has the potential to bring opportunity and uplift to children regardless of their economic status.

Jan Resseger is the minister for public education and witness with the national Justice and Witness Ministries of the United Church of Christ. She spoke with Sojourners associate editor Julie Polter in June.

Sojourners: Why is public education a commitment for the United Church of Christ?

Jan Resseger: The commitment to education is a long tradition for us. Our pilgrim forebears brought community schooling and higher education to the New England colonies—New England congregationalism is one of our denominational roots. Another root is the American Missionary Association (AMA), an abolitionist society that grew out of the defense committee for the Africans on the slave ship Amistad. The AMA founded schools for freed slaves as a path to citizenship across the South during and after the Civil War.

Several denominations came together as the UCC in 1957, and our general synods since then have taken stands on issues such as the protection of the First Amendment in public schools and supporting school desegregation through the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. From 1958 to the present, we have spoken to institutional and structural racism and classism in schools. We also have addressed privatization, because we’ve been strong supporters for many, many years of public schools as key to the strength of our society and democracy.

THE SO-CALLED “accountability movement” has been a bipartisan movement; virtually no one is proposing that we cut back on standardized tests. They’ve come to dominate school for children and teachers, and they’ve narrowed the curriculum. They’ve caused people to feel pressure to cheat. While standardized tests have been emphasized less in schools where children are highly affluent—those children still get an enriched curriculum—children in schools that are poor get a heavily test-prep curriculum that’s not very enticing.

At a higher level, standardized tests are at the core of the test-and-punish philosophy of No Child Left Behind (NCLB). All the punishments are based on test scores; whether it’s identifying failing schools and closing them if their scores are too low or giving teachers poor evaluations, and maybe firing them, based on student test scores—or whether it’s the very draconian ways of dealing with the bottom 5 percent of schools in the NCLB waivers and Race to the Top grants, as Education Secretary Arne Duncan proposes.

High-stakes testing is at the core of what’s wrong with where we’re headed. Because the stakes are so high, they’ve caused a narrowing of the curriculum. The tests required for NCLB are basic reading and math. They don’t test social studies or the arts. Because the scores matter so much, they’re driving policy all around it.

I'VE BEEN INVOLVED in public education for more than 15 years—as an urban public school teacher, a researcher and policy analyst, a teacher trainer, a parent, and an advocate. I never dreamed I’d live to witness such raucous and juicy debates about how to improve our nation’s lowest-performing public schools. Throughout my career, public education garnered the occasional feel-good story about a phenomenal, mythical “inner city teacher” and, more often, the litany of stories about how urban and rural schools are in complete disarray.

But during the last few years—oh my! We’ve witnessed the onslaught of message-laden documentaries such as Waiting for “Superman” and The Lottery, which are celebrated by many and derided as teacher-bashing propaganda by others. The birth of the “education reform” movement has generated such groups as Democrats for Education Reform, Students for Education Reform, and Stand For Children. Again, lauded by many, these groups are vigorously criticized by others because of the way they push against policies, structures, and institutions in public education.

Regardless of what side of the education reform debate we may choose, most Americans agree on one thing: Public schools must improve. The academic achievement gap between wealthy white students and low-income students of color must be eliminated. It’s unconscionable that 50 percent of kids growing up in poverty drop out of high school. How do we allow a system to exist where poor children in the fourth grade are already performing three grade levels behind children in wealthier neighborhoods? What future do we anticipate poor and minority children will have with these academic outcomes?

JUST OVER A year ago, I attended a retreat sponsored by the Fund for Theological Education. During the retreat we were encouraged to look at our lives and to find a personal story that captured the essence of what led us to our particular ministries. That led me to reflect on my childhood: growing up in poverty, attending a different school every year, walking to school with cardboard in the bottom of my shoes because the soles were worn out, wondering how I was going to eat, lacking school supplies at times, and dealing with the stress of a single mother who was a substance abuser.

By reminding me of those things I endured and had to overcome as a child, that exercise helped me tap into my real passion. I wanted to find ways to help children growing up in similar circumstances. I wanted to inspire them to believe in themselves and know that they can make it.

At-risk youth and under-performing students need to be inspired, but equally important is their need for adults who are willing to do the work of helping them succeed academically. Education continues to be our most reliable tool for creating upward life trajectories and optimal opportunities. Churches are more than places where people come in search of a deeper relationship with God; they are also places where people come to find deeper connections with their communities and the possibility of using their gifts and talents to help those in need.

All these forces together compelled me to act on an idea I had more than a year ago: to call on friends from across the country to help create Faith for Change. Faith for Change builds a national network of churches and people of faith committed to implementing proven educational strategies for improving children’s lives.

Jonathan Kozol, author of Fire in the Ashes, talks about the gripping stories of poor children, the problems of “obsessive testing,” and how to build a school system worthy of a real democracy. An interview by Elaina Ramsey.

Imani walked down the hall with a paper cup in her hands.

She stopped and held up the cup to me. Inside of its paper walls were soil, water, and seeds — all those humble and elemental things that build a third-grader's scientific knowledge.

Imani was growing cabbage.

She was my student last year. She loved science and writing. I remember the look of wonder in her eyes when we studied weather. We learned about tornadoes. In my classroom, I had two 2-liter bottles connected by a tornado tube, a plastic piece that allows you to make a tornado by swirling the water around and around in one of the bottles. Imani held the bottles in her hands and marveled as her water formed into a giant, powerful funnel cloud.

"Wow," she whispered.

I love the sound of learning.

In Roald Dahl's classic children's book James and the Giant Peach, 7-year-old orphan James Henry Trotter escapes his two rotten, abusive aunts by crawling into a giant peach. The peach rolls, floats, and flies him to a new life of wonder and love.

I'm reading this book aloud for the first time, and my listeners are spellbound by the story, especially the part where the very small old man opens the bag filled with magical crocodile tongues that will help a barren, broken peach tree grow fruit as big as a house.

"There's more power and magic in those things in there than in all the rest of the world put together," says the man.

There is.

"Teachers are builders," said my friend. "You build safe learning environments for your students. You build safe spaces for your parents. You build knowledge and experience for yourselves. You build community with each other. You are builders."

I like her image.

This year I'm going to work on the 'building community with each other' part.

I don’t mind failing as much as I do admitting I’ve failed. And technically, we haven’t blown the SNAP Challenge just yet, but I know for a fact we will by the end of the week.

I went to the store last night for another loaf of bread and a frozen pizza for dinner, which I had promised my kids if they’d make it to mid-week without freaking out. This brought us down to eighteen bucks and change left in the till, which theoretically was going to be enough to fill in the gaps for other items we’d need to do our meals through the weekend.

And then reality hit.

Maybe the serpent in the Garden of Eden story actually was a cute little girl in pigtails. Sure would have been more persuasive than some stupid talking snake.

Explaining to kids who have grown up their entire lives with such privilege is almost like trying to translate a foreign language for them. No, not everyone just goes in and grabs whatever they feel like from the fridge or the shelves. They don’t order in when they’re too tired or lazy to cook, and they don’t mark every mundane occurrence in their lives with a celebratory dinner out. It’s normal to them, but that doesn’t mean it’s normal.

I've been having little arguments with myself all week: on one hand, like many good Americans, I believe in the idea and potential and creativity and wonder of individuals. I believe that the mind, for example, is a fathomless miracle. I believe that individuals have certain rights to freedom and self-determination.

Yet at the same time, everything that we are has been given us. We carry in our bodies the genes of thousands if not millions of ancestors; we have been brought to this moment — every moment — by people whose care and attention and patience have loved us imperfectly along. And, of course, by the God who has loved us into being.

Those of us who have the gift of being able to read and write often also have the ability to learn and to choose — to choose where to live and with whom, to choose what to think and to believe and to consume. And that, compared to how most people have lived and do live, is an almost unimaginable luxury. We can choose.

Ever since the global financial cabal drove the world's economies into a ditch, popular movements have been rising up to fight "austerity measures" that exact punishment on the poor and leave the rich untouched. This is a familiar biblical meme for the definition of injustice. The words of the prophet Jeremiah come to mind: "Your clothes are stained with the blood of the poor and innocent" (Jeremiah 2:34).

"When Spanish mayor Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo recently led farmers on a supermarket sweep, raiding the local shops for food as part of a campaign against austerity, his political immunity as an elected assembly member protected him from arrest. He now asks other local mayors to ignore central government demands for budget cuts and refuse to implement evictions and lay-offs. In this era of austerity, such flagrant disrespect for the law ought to be encouraged. Sometimes, the greatest strength of popular movements is their capacity to disrupt. So here, for the benefit of imaginative indignados, are five examples of civil disobedience:

I’m not making friends among my family members with this challenge.

Because it was my idea to do this for a week (living on the equivalent budget of food stamps for seven days), everyone ends up coming to me to “check on the rules.” Basically, this means they ask me about ways they might work around the limitations of the challenge, and then get mad at me when I don’t give them a way out.

Yesterday ended up being a mixed bag. My wife, Amy, and I had to go to the other side of town for some errands, and it didn’t occur to either of us that we’d be gone over lunch time. Fortunately, one of the errands was at an Ikea, a giant housewares store that’s known for it’s affordable cafeteria-style meals, so we made it work. But even with their reduced-rate prices, we spent more than $9 for both of us and little Zoe to eat.

“Man,” I said, looking at my empty bowl, previously filled with pasta and Swedish meatballs, “that was way less than we usually spend going out, but it was still almost double what we have in the budget for one meal.”

Editor's Note: Over the next two weeks, Sojourners is celebrating our teachers, parents, and mentors as children across the country head back to school. We'll offer a series of reflections on different aspects of education in our country.

My elementary school is a Title I school. About 97 percent of our students qualify for free and reduced lunch and Medicaid. Research shows us that many children raised in poverty struggle to learn to read.

Common sense tells us that children who don't learn to read can't read to learn. They often reach a frustration level with school by the time they're in the third grade. According to the U.S. Department of Education, 70 percent of low-income fourth-grade students can't read at a basic level. I often wonder, "What can I do in my day-to-day work as a teacher to help?"

“So what are food stamps anyway?” my 8-year-old son, Mattias, asked as I drove him to his summer camp this morning. “Are they, like, stamps that you eat that taste like different foods?”

“Not exactly,” I said.

My family was less than thrilled when I presented the idea of living on the equivalent of what a family of four would receive on food stamps for a week. Actually, the program is now called “SNAP,” which stands for “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” and involves government-issued vouchers or debit cards, rather than the antiquated stamp method. But the result is the same; we have a lot less to spend on food this week than usual.

“But I don’t want to be poor,” Mattias moaned as I explained the challenge to him.

“We’re not poor,” I said, “but it’s important for us to know what it’s like to struggle to feed our family.”

“Why?”

“Because,” I paused, trying to figure out a way to explain privilege and compassion to a third-grader who was quite content to have all he has, and then some, “Jesus tells us to have a heart for the poor, but how can we really do that if we don’t know anything about what it’s like to live with less?”

“Hmm,” he wrinkled his brow, “I guess we can do it for a few days.”

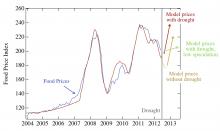

The advocacy group Stop Gambling on Hunger reports world food prices are predicted to rise sharply in the coming months, due partly to speculation:

"The New England Complex Systems Institute, [which has] developed a quantitative model able to very closely predicted the FAO’s food price index, released a new report predicting sharply higher food prices due in part to excessive speculation.

"Their model, originally released in September 2011 matched the FAO’s index from 2004 to 2011. Since then it has continued to closely follow the real world numbers.

"Unfortunately, the model now predicts, 'another speculative bubble starting by the end of 2012 and causing food prices to rise even higher than recent peaks.'

"While the researchers acknowledge that the drought in the Midwest U.S. will cause prices to rise, their model shows that excessive speculative activity will have an even larger effect. Though some key financial reforms passed in 2010 may finally begin to be implemented in early 2013, that may be too late to avoid the coming price bubble."

Read the rest of the article here.

As conflict, rape, and other human rights abuses continue in eastern Congo, armed groups are still funding themselves with conflict minerals — gold, tin, tantalum, and tungsten — which are often used in the manufacture of cell phones, computers, and other electronics. Now advocacy group The Enough Project has issued a new report card about how well different corporations are doing at cleaning up their supply chain to avoid contributing to violence.

Some companies, such as Intel and HP, are doing much better than others — get an ethical clue, Nintendo! — but everyone has some room for improvement.

See the rankings here or take in the chart-at-a-glance here.

After putting out there that we’re going to do the SNAP Challenge August 20-26th (living on the budgeted equivalent of food stamps for a week for meals), some folks came forward with some really helpful resources. Even if you’re not on public assistance and not planning to take part in the challenge, these are useful tools to help anyone on a budget plan for some good, nutritious meals.

Here’s a video clip on meal prep with only food bought on the food stamp budget, along with the list of groceries the chef bought on the budget: Mario’s Food Stamp Challenge Grocery List

Here are dozens of recipes from Harvesters Food Network you can do on a food-stamp-equivalent budget, complete with nutrition information for each meal: Harvesters Food Network SNAP Recipes

I’ve said before that privilege often is invisible until you don’t have it. So in that light, I’m doing a little experiment in a few days with our family, and I encourage you to join in.

A lot of us never know what it’s like to try and live below the poverty line, and I tend to think the statements we hear about the poor that lack sensitivity for their situation point to this. It’s easy to say things like, “people on public assistance are lazy” (in fact, 47 percent of SNAP recipients are under 18; a majority of the remaining recipients have other income from work, and this doesn’t account for seniors and those who are disabled) and that food stamps are a “free ride” that are so attractive, it keeps people from wanting to work and get off of the assistance.

So let’s find out just how easy it is.

“SNAP” stands for “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” which is the new name for food stamps. Basically, families receive $4 a day per family member to cover food costs, so the SNAP challenge is pretty simple (in theory, at least): Live on the same amount with your family for a week.