Advent

A LOT OF BEGGING happens at Christmas. There are pleas in the toy aisle and hints left open on laptops. But no one begs to be in labor. Not even a woman who is pregnant. Unless, of course, she is at the bitter end of her pregnancy.

In the language of King James, Luke tells us that Mary is not just pregnant, but she is “great with child” (Luke 2:5). She is on the cusp of birthing, of being the first one to slide her hands up under the armpits of the warm, slippery flesh of God. No one before or after will have God in quite this way.

In Mary, the Word became flesh and was born in the most mundane, most primal human act. This flesh must count for something. The extremely pregnant body of Mary — great with child — reveals the nature of our waiting for Christ and what it might mean to cry out for Jesus’ coming.

As a midwife, I have delivered more than 1,300 babies, and I have given birth three times myself. But you don’t need a midwife or someone who has had a baby to tell you about the discomforts of pregnancy. Nausea, headaches, food aversions, and swelling are common enough knowledge. As unpleasant as these symptoms are, they aren’t enough to make anyone beg for labor. For most of a pregnancy, the woman is largely herself and retains her sense of self.

So, if I told someone who’s 32 weeks pregnant that she had to go into labor tomorrow she would be utterly unwilling. That her baby would easily survive the labor does not change this fact. You don’t need a midwife to tell you why she might not want to labor. No one wants the searing pain of contractions, pushing, or tearing. To be in labor is to be completely beyond yourself, given over wholly to another, and the pain of its outworking.

We know, or suspect that we know, the gravity of the transformation a pregnant woman is about to endure. And we want to help her, we do. We want to come alongside her and acknowledge and aid her work. But our culture fails us. “Birthing classes,” though helpful, are as inadequate as “dying classes” would be — there is no way to simulate or teach the courage required of a soul in extremis. The closest thing we have to a rite of passage for initiating a woman into motherhood is the baby shower. Onesies and party games do not prepare someone for the maelstrom of birthing and raising a child.

THERE IS MUCH anticipation in the air. During Advent, we eagerly await the Christ child among us and all the blessings and transformations this infant brings. Our readings during this season remind us of the Christ child’s vision for our world — and of God’s power to upend existing political orders. This is the child whose mother proclaims that he will “cast down the mighty,” “lift up the lowly,” and change the course of history for God’s people. We welcome the arrival of new life in Christ, imbued with hope and reminders that life is never fully defeated by empire’s death-dealing designs.

But this Christ child comes in many guises. This child appears as an unhoused person, a racial other, an incarcerated person, a foreigner. Will we receive every child of God as we receive the Christ child and honor their hopes and full potential? Will we give to all of God’s children the gifts of our time, energy, joy, and relationship so that our communities become hospitable places for the Christ child and every child?

Indian artist Jyoti Sahi has a beautiful painting called “Incarnation within the Anthill.” In the image, Sahi sets a tightly curled Mary and infant Jesus inside a tall insect mound. In some parts of India, these mounds are called the “ears of the earth.” As numerous, tiny, and insignificant as ants may seem, they are sacred and have inherent value, just as the mother and her newborn child have. It requires deep listening to nurture this Christ-consciousness. May the Advent season remind us that every child is sacred and that honoring God’s image in the tiniest ones can bring down empires.

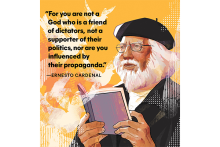

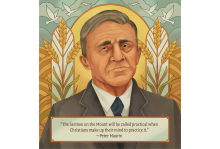

POET MARY OLIVER describes the world calling us “like the wild geese, harsh and exciting.” As we approach Advent, Christians ponder words like annunciation, waiting, and hope. Midwife Julie Dotterweich Gunby plumbs the theological depths of expectation and asks if we are truly “ready for Christmas.” Before we celebrate Christ’s birth, we must wade through the consequences of a U.S. election. (This issue went to print before November.) If we zoom too far out, our vision becomes binary — red/blue, us/them, win/lose. If we look more closely, we see active civic engagement, and a robust obligation to protect the democratic process. We also glimpse ties that bind us around the world. Stephen Schneck chronicles Nicaragua’s fall into autocracy, a cautionary tale. Chris Hedges and Mae Elise Cannon take readers to Palestine and Jerusalem’s Armenian Quarter, respectively. Liuan Huska travels to Ann Arbor, Mich., to report on a “farm-to-altar” Communion bread project reminding us that we are what we eat. “Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,” concludes Oliver, the world is “announcing your place in the family of things.” Welcome. You belong.

For many Christians in the West, Advent is a time of preparation infused with prayer, anticipation, and reflection. This year, Advent is painfully marked by more than 18,000 Palestinian deaths — including more than 7,000 children — as a result of Israel’s brutal military retaliation for the Oct. 7 Hamas attack. But the violence stretches beyond the borders of Gaza and the West Bank.

My first experiences of Christian sacraments, including baptism and the Eucharist, were mysterious and somewhat confusing. As a Catholic little girl, I didn’t remember my infant baptism and could never quite wrap my head around eating Jesus’ flesh and drinking his blood. What’s more, these solemn events happened within the confines of a giant, cavernous church — a place where I had to be still, quiet, and serious. During weekly Mass, I learned implicitly from the nuns that reverence and fun do not go together.

“THE CONTEMPLATIVE ON her knees well knows the messy entanglement of sexual desire and desire for God,” writes theologian Sarah Coakley. If she’s right, then attending to what arouses us sensually can teach us something about how God lures us through our longing and, even, how we can attract God’s intimacy. This month, we’re exploring how queer theology can invigorate (dare I say, stimulate?) the anticipation we build throughout Advent. This approach may seem blasphemous to some who aren’t familiar with a queer-affirming lens ... and perhaps uncomfortable to some who are. Many of us are steeped in Christian body-denying theologies and moralities. We are uncomfortable meeting God in ways that are playful, erotic, unnerving, and always cognizant of power dynamics (though scripture is steeped with such sexual innuendo). Queer theology starts from (rather than argues for) not just queer affirmation, but queer celebration. It can expose the erotic dimensions of our sacred stories to reveal God’s wild and promiscuous desire for all creation.

December is a season for sending Christmas cards depicting the Holy Family — perhaps the most heteronormative image in the church year: A mom and dad stare lovingly at their beautiful baby. This static image can obscure the mess of desire, power, submission, and surprising gender fluidity required to incarnate this Holy Child. What moves in us as we ponder the design of different Christmas images that don’t shy away from this beautiful mess? What images help us face the wonder and terror of what it feels like to be undone and remade by God’s overcoming?

THE FERVOR AT church during the Advent season is a remarkable sight. Both clergy and laity work like the shepherds, tending to their flocks late into the night. And many move like the wise men, traveling to foreign places and spending extensive resources to celebrate Christ’s arrival with family.

This time of heightened activity makes sense given the story of scripture and the story of our current world. The shepherds could not help but tell others once they learned of the Savior’s birth. And as we now await his return, we shouldwork hard to share the riches of the nativity with a world that is a little more open to matters of faith at this time of year.

But if increased activity is the only melody we pick up from the nativity story told in Matthew and Luke, we neglect a needful counterpoint: the importance of rest. The nativity story is replete with theological, familial, and political lessons about rest that quietly proclaim God’s goodness to this weary world. With exhaustion rampant in the church — perhaps especially so at Christmastime — we would do well to hear notes of rest sounding from the manger.

1. Listen to your sleep

God uses sleep as a vehicle for saving Joseph’s family (Matthew 1:18-25). God instructs Joseph to honor his marriage to Mary because her pregnancy was not a sign of infidelity. To the contrary, it was a sign of immense devotion to God. Furthermore, this miracle child would save all his people, including his parents, from their actual sins, as opposed to their alleged ones. In obedience, Joseph listened to the message heard in his sleep and thus participated in God’s saving of his family.

As we go to press, violence again erupts in the Holy Land. In the season of Advent, we prepare for the birth of the Prince of Peace in a rough shelter in a Palestinian village and hear again God’s ancient promises first given to the Hebrew people. But all is not calm in Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Gaza, or Ashkelon. The agitations of injustice and fear have turned a season of dreams into one of nightmares.

ACROSS THE UNITED STATES, people will soon be preparing for Thanksgiving. We’ll name what we’re grateful for and then, in an ironic turn, let “Black Friday” convince us we need more. “Cyber Monday” will catch all the credit cards that made it, un-maxed, through the weekend. “Giving Tuesday” lets us pay the virtue toll to keep spending guilt-free on the yet-to-be-named following Wednesday. Whew! The consumerist drive in November and December makes the temporality of liturgical living difficult. But let’s try. November marks the end of both Ordinary Time and the church year. Ordinary Time is the day-in, day-out rhythm of everyday life as we await Christ’s second coming. In these final weeks, we’re not quite waiting on Christ, then — as we do during Advent — so much as we’re preparing ourselves to wait.

Come Advent, the scripture readings will be filled with anticipatory hope. But, as the old church year ends, the passages are full of anxiety and dread. The Hebrew Bible selections spotlight the escalating threat of the coming judgment. Paul’s letters pour out end times panic. Or, as songster Leonard Cohen put it, “Everybody knows it’s coming apart.” In Matthew’s gospel, Jesus forces us to ponder which side we are on. It’s not easy to sit with all this. I want to skip over to Advent hope (or even Christmas joy). But I invite us to hospice the old year’s death throes before welcoming new life at the stable door.

God’s promise in Advent is about meeting us wherever we are. We, too, can go out and build relationships with all our neighbors — housed or unhoused, incarcerated or not — as we prepare for a future where all people can be comforted.

I can’t deny the unbridled excitement that this global phenomenon unleashes every four years. And since this year’s tournament is taking place in November (to avoid Qatar’s crushing summer heat), the international fervor coincides with the start of Advent. Somehow, it all feels fitting.

A FEW YEARS ago, I set out to knit a baby blanket as an Advent prayer practice. Knitting is incredibly meditative and allows me to pray with focus and clarity. Knitting a baby blanket seems appropriate as the church awaits the arrival of the “newborn king.” I wish I could say I finished the blanket in time for Christmas. I did not. However, even that seems appropriate, as so much remains unresolved for Jesus’ community at his birth. Their political occupation continued, and even Jesus’ birth story reflects the impositions placed upon his family by the Roman Empire. God’s inbreaking happens under serious duress — but it happens nonetheless.

My favorite lines from the poem “Christmas is Waiting to be Born” by Howard Thurman are: “Where fear companions each day’s life, / And Perfect Love seems long delayed. / CHRISTMAS IS WAITING TO BE BORN: / In you, in me, in all [hu]mankind.”

Thurman reminds us that God was born into our sorrow and among those who are brokenhearted and struggling. That truth is so important to hold on to as we process years of our own collective trauma. No matter how unresolved things are, Christmas is born in us, too! In December we continue our journey through Advent and arrive at Christmas. We might not have received what we’re waiting for by that time, and very little may make sense. Yet, because of who God is, we open our hearts to the improbable, trusting that we won’t be put to shame.

IN THE EIGHTH season of Call the Midwife, set in post-war east London, nuns and nurse midwives of Nonnatus House assist a woman with severe complications from a “backstreet” abortion. Sister Julienne says to a young nurse, “The word ‘midwife’ means ‘with-woman.’ A woman in that situation needs somebody by her side.”

I’m pro-choice, which was an unpopular stance in the Catholic community I grew up in. For my views on reproductive rights, people in youth group called me a “baby killer” and “Pontius Pilate.” During Advent, specifically, I loathed the hollow teachings on Mary and childbirth. We sanitized the Nativity into a cute story — the equivalent of a Disney movie featuring a white family and a manger crowded with men. Only recently did I learn that some scholars believe that midwives attended Jesus’ birth. As reproductive freedom and care are further undermined in the United States, this is an apt time to reclaim a more feminist view of the Nativity and rethink Advent as the season of the midwife.

Activist Vanessa Nakate on Jesus, erasure, and the climate crisis in the Horn of Africa.

WE ARE APPROACHING the end of the liturgical year, and the texts have a thread of anticipation running through them. We are deep into the promises conveyed by the prophets and the eschatological vision cast by Jesus. The texts are inviting us to prepare ourselves for something — but what, exactly?

The last Sunday in November, in many traditions, is the Advent Sunday of hope. In biblical Greek, the verb is elpizō (“hope”), which means to wait for salvation with both joy and full confidence. When we hope, we wait not out of boredom or a lack of options but in full confidence that what we are waiting for will arrive. This is the same word used in Hebrews 11:1, “Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” The word “assurance” here can also be translated as “foundation,” as in that of a house. Faith is what anchors our hope into the ground and allows it to stand upright. Faith also often requires that we act before we see. Our hope is first materialized in our faith before it is ever materialized in our reality. Hope pushes us to walk, move, and live as if what we’ve hoped for has already arrived.

Perhaps this moment calls to us to build foundations for the futures we need in defiance of our present realities. Our texts dare us to live into new possibilities, even as our current condition offers far fewer promises.

The season of Advent holds a special meaning for me because it reminds me of the power of a mother’s love. While I know “Jesus is the reason for the season,” I cannot help but shift my attention to the woman who brought him into the world — and what she had to endure to birth him.

At its core, the Christmas story is radical. Christ enters the world in the form of a marginalized infant — a story about finding hope amid brokenness by pushing forward into the darkness. We cannot find the true light of Christmas without understanding what it means to be in the dark, opening our eyes to the injustices in our neighborhoods.

In Matthew 25:35, Jesus identifies himself with the stranger we welcome or exclude. Advent hospitality extends beyond our personal relationships and into the ways we structure our neighborhoods and our common life. But in the United States, our politics are driven by “NIMBYism” (“not in my backyard!”), as housed individuals and politicians not only demand the exclusion of unsheltered people from public spaces but also oppose the creation of shelters and permanent, affordable housing in our neighborhoods.

Christians believe that God’s reign of righteousness, steadfast love, peace, and justice is not just a promise relegated to the future. Instead, we see glimpses of that heaven in the here and now, even as we face the realities of suffering and grief all around us. This means that Christ’s birth in Bethlehem makes it possible for us to co-labor with God in yanking pieces of heaven and bringing them closer to Earth.

As I observed and engaged in the multifaceted conversations about abortion, I came to a stark realization: In the story of the Annunciation, God reveals the importance of consent, agency, and women’s rights. This season of Advent presents us with the perfect opportunity to look at the Annunciation from this perspective.