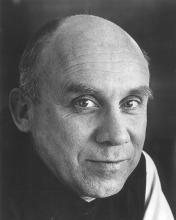

Thomas Merton

Divine Love

Loved Into Being is a tender five-part film series inviting us to rediscover our belovedness in God. James Finley — who was mentored by Thomas Merton — explores how “the divinity that shines forth out of broken places” can heal our wounds and reimagine community. The Work of the People

THIS SPRING, I moved to California. Nature, culture, family, and work beckoned my partner and me, and once we arrived, we found ourselves immersed in sweetness: picking roses in our friend’s garden so fresh they smelled like citrus; sharing weekly dinners with my brother; and swimming in the Pacific Ocean. In that water, I’ve felt swallowed by mystery. The airborne salt, the bone-cold temperature, and the wild waves refine my ability to listen to the hum of the earth. In the Christian tradition, the ocean’s role in shaping consciousness is robust. Through their writing on “contemplative ecology” and reflections on the Pacific, contemplative theologian Douglas E. Christie, Lutheran scholar Lisa E. Dahill, and mystic Thomas Merton have helped me embrace the ocean as a healing partner.

Christie, author of The Blue Sapphire of the Mind: Notes for a Contemplative Ecology, describes “contemplative ecology” as dual-natured: a spirituality that centers the natural world and “an approach to ecology” that relies on “contemplative awareness.” He posits that connecting contemplation to the environment helps make us more “porous,” more attentive, and clearer about the world as a “sacred [and beautiful] whole.”

It is especially important, and equally challenging, to see the world as sacred and beautiful amid the global climate crisis.

A MONK DIES much as he lived—in holy obscurity. That’s the goal at least.

Father Maurice Flood lived as a Trappist for 64 years. At his funeral in August, his abbot described Maurice’s monastic journey as “atypical.” And so it was.

To enter the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (Trappists), one vows silence, stability, poverty, chastity, continual conversion, and obedience to Christ (in the person of one’s abbot). When I met Maurice in 1980, he was uproariously funny and riding his Harley-Davidson around the U.S. with a homemade telescope strapped to the side. Though neither silent nor “stable,” his other vows appeared to hold firm.

LIKE MOST POETS, she is largely unknown, but 97-year-old Catherine de Vinck can live with that. She has a dozen published volumes to her credit, a collection titled The Confluence of Time that she is working to publish, and the love of Christians drawn to the sometimes-shaky Jacob’s ladder of contemplation and social action. Thomas Merton was among her readers.

“Nothing stands still long enough / for us to find the first imprint / to grasp the pure moment of origin. / How then can we see the world as it is,” she writes in her poem “Ever-Changeless/Even-Changing.”

IN 1948, A HERMIT was made known to the world by another hermit. Like many Christian holy men, the Jewish-born Catholic contemplative and poet Robert Lax had his early spirituality enshrined in a book: The Seven Storey Mountain, the bestselling autobiography authored by his friend, the Trappist monk Thomas Merton.

“He had a mind naturally disposed from the very cradle to a kind of affinity for Job and St. John of the Cross,” Merton wrote about Lax. “And I now know that he was born so much of a contemplative that he will probably never be able to find out how much.”

Better known to many for what was written about him than for what he wrote (and he wrote a lot), Lax, who died in 2000 at age 84, wanted, according to his archivist Paul Spaeth, “to put himself in a place where grace can flow.” For Lax in the 1940s, New York City was not such a place. Though he worked with the poor at Baroness Catherine de Hueck’s Friendship House in Harlem, and had enjoyed jazz with Merton, he balked at the gaspingly fast pace and materialism of the city. He was also unhappily employed at The New Yorker.

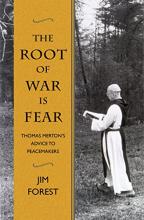

DO WE LIVE in a post-Christian era? Catholic monk Thomas Merton thought so, back in 1962, when his anti-war book Peace in the Post-Christian Era was banned by monastic censors.

He would surely come to the same conclusion today, when we hear a pulpit Christianity still identified with war and nationalism and listen in shock to a new U.S. president woefully ignorant of the peril of nuclear war. Our deeply divided nation holds scant promise for peace in our streets or in the world, despite the growing chorus of Christian peacemakers.

This new book by Jim Forest adds both deep compassion and timely advice to that chorus. The wise words of Merton, who served unofficially as “pastor to the peace movement” during the Vietnam War, are needed now more than ever. Clearly titled chapters quote from Merton’s published writing as well as his letters to Forest and other peacemakers.

In October 1961, The Catholic Worker published Merton’s essay “The Root of War is Fear,” and Merton ran afoul of monastic censors. He was eventually silenced publicly but fortunately was allowed to circulate Peace in the Post-Christian Era in mimeographed form and to continue writing letters, although for several years everything passed through the censor’s hands. One of the delights of this book by Forest is the first publication of an uncensored and scathingly sardonic letter Merton wrote under the pseudonym “Marco J. Frisbee.”

The name Berrigan helped keep the possibility of coming back to my Christian aith alive. Just like the black churches that took me in, here were some Christians who were saying and doing what I thought the gospel said that nobody in my white evangelical world was. I believe the witness of the Berrigans literally helped keep my hope for faith from dying altogether.

I was reading The Infinity of Hours, which is about the last order of Carthusian monks before the order was changed in the sixties, and one of the monks wrote a letter home and was just bitching about Thomas Merton. I was like, “Of course other monks had opinions!” It did not occur to me, but of course he was this huge, famous monk in the sixties — of course other monks are going to be like, “Well, he needs to spend more time monkin’, and less time writing his famous books.” And [the monk] was like, “I’ve never thought too much about Thomas Merton, I think he needs to decide if he’s a celebrity or a monk.” And it’s just so charming, this little monkish bitchery.

At his speech before Congress on Sept. 24, Pope Francis listed Trappist monk Thomas Merton as one of four exemplary Americans who provide wisdom for us today.

Out on the National Mall, thousands cheered when the pope named two other exemplary Americans: Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. Fewer recognized Merton (or the fourth exemplar the pope mentioned, social activist Dorothy Day.)

The pope did not choose to hail anyone associated with the institutional Catholic Church as his models. Instead he chose a former president, a Protestant minister, a lay Catholic, and a monk.

If the influential Catholic writer Thomas Merton were alive today, he would likely have strong words about police brutality and racial profiling.

Back in 1963, Merton called the civil rights movement “the most providential hour, the kairos not merely of the Negro, but of the white man.”

His words echoed May 16 among black pastors at a conference, titled Sacred Journeys and the Legacy of Thomas Merton, hosted by Louisville’s Center for Interfaith Relations. The event marked the 100th anniversary of Merton’s birth.

In the last several days, our country has witnessed and experienced, yet again, the effects of the unresolved issues of racism. We cannot rest complacent, convincing ourselves that everything is and will be all right on its own. That is a lie. The racial divide in the United States is boiling — we see the big cloud that rises over the roaring mountain. If we don’t act, the volcano will eventually explode. Our all-gracious God is calling us to turn from our wrong path.

Above other civic institutions, the church is responsible to do the work of healing. Our nation is desperately in need of healing. The sins of racism, classism, violence, and ideological intransigency are violently shaking and destroying the soul of our nation.

Where are the godly leaders in our country who are ready and willing to strip their souls of religious and ideological allegiances and surrender without fear, to seek the path that the Holy Spirit is eager to show us?

There is a way forward. We know that Jesus the Christ came to show us that way. We need to quit insisting that the way forward is my way. It is not my way — it is Christ’s way. No one Christian leader can claim to speak for God. Neither does God need any one of us to make the way clear — God can speak for God’s self.

There is one condition necessary for us to hear God’s voice: “If my people who are called by my name humble themselves, and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven and will forgive their sin and heal their land.” (2 Chronicles 7:14.)

Someone once said that change happens by listening and then starting a dialogue with the people who are doing something you don't believe is right. There is no virtue in sticking to our allegiances. Our allegiances should not be to the right or the left or even the center. If we follow Jesus, our allegiances are to repentance, forgiveness, and reconciliation. Our life and our only hope are found in the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Thomas Merton wrote, “You do not need to know precisely what is happening, or exactly where it is all going. What you need is to recognize the possibilities and challenges offered by the present moment, and to embrace them with courage, faith, and hope.”

The truth is that we do know what is happening, and we know what is going on. Our individual and collective sins are robbing us of our dignity. We, the Christian leaders of this country, can choose to wage war with the weapons of our ideological, denominational, and theological perspectives and convictions. Or we can choose to “recognize the possibilities and challenges offered by the present moment, and to embrace them with courage, faith, and hope.”

WHILE NOT HERE in person for the celebration of his 100 birthday on Jan. 31, Thomas Merton is certainly present in spirit through the extraordinary number of volumes about and even by him being issued to mark the anniversary—a splendid opportunity for readers to acquaint or reacquaint themselves with the monk often considered the most significant American Catholic writer of the past century.

Perhaps the best place to start is Messengers of Hope: Reflections in Honor of Thomas Merton, edited by Gray Henry and Jonathan Montaldo (Fons Vitae), a collection of more than 100 reflections by monks and activists, scholars, filmmakers, and poets, and Christian, Jewish, and Buddhist practitioners on the significance of Merton for their own lives. Some of the contributors are well known—Joan Chittister, John Dear, Jim Forest, James Martin, Richard Rohr, Huston Smith; others are well known in Merton circles; some are younger voices who one day may become well known but already have valuable insights as to how Merton continues to speak to the needs and hopes of the contemporary world. This is a rich compendium of personal stories that is a delight to dip into or to read straight through.

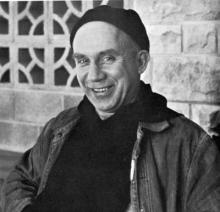

IN OCTOBER 1968, the renowned Trappist monk and spiritual writer Thomas Merton set out for Asia on what would be his final pilgrimage, desiring “to drink from [the] ancient sources of monastic vision and experience.” From his monastery in Kentucky, he had long dreamed of meeting with Buddhist teachers face to face, close to the sources of Eastern mysticism, and fulfilling what he believed to be the vocation of every Christian: to be an instrument of unity.

Three times during his journey Merton met with the young Dalai Lama, who would later say, “This was the first time that I had been struck by such a feeling of spirituality in anyone who professed Christianity. ... It was Merton who introduced me to the real meaning of the word ‘Christian.’”

After Merton’s sudden death in Bangkok on Dec. 10, 1968—the result of an accidental electrocution—his body was returned to the U.S. in a military transport plane that carried the bodies of soldiers killed in Vietnam, a war he had condemned forcefully. His body was laid in the earth on a hillside behind the monastery, overlooking the Kentucky woods where he lived as a hermit the last years of his life. Pilgrims from all over the world continue to visit the Abbey of Gethsemani and pray before the simple white cross that marks Merton’s grave. Why? One hundred years after his birth, the question is well worth asking. What particular magic draws seekers of every generation and of such remarkably diverse backgrounds to Thomas Merton?

SON OF A CENTURY

Merton’s appeal to postmodern sensibilities may be explained in part by his own renaissance background. Born in France in 1915 to an American mother and a New Zealand father, itinerant artists who had met in Paris, Merton spent much of his youth traveling between Europe and America. By the time he was 16, both of his parents were dead. He enrolled at Cambridge, but his raucous behavior there quickly prompted his godfather to send Merton back to the U.S., where he enrolled at Columbia University and soon thrived among an avant-garde group of friends.

More and more he found himself drawn to Catholic authors, devouring works by William Blake, Gerard Manley Hopkins, James Joyce, and Jacques Maritain. As he later described this period, something deep “began to stir within me ... began to push me, to prompt me ... like a voice.” To the shock of his friends, Merton announced his desire to become a Roman Catholic and was baptized on Nov. 16, 1938, in New York. Two years later Merton began teaching English at St. Bonaventure. After spending Holy Week of 1941 on retreat at the Abbey of Gethsemani in the hills of rural western Kentucky, Merton decided to become a Trappist monk, part of a Catholic religious order of cloistered contemplatives who follow the 1,500-year-old Rule of St. Benedict.

It was the publication in 1948 of his autobiography,The Seven Storey Mountain, set against the shadow of World War II, that established Merton as a “famous” monk and a wholly unexpected literary phenomenon. In addition to publishing spiritual meditations, journals, and poetry, during the 1960s he published penetrating essays in both religious and secular venues on the most explosive social issues of the day, the religions of the East, monastic and church reform, and questions of belief and atheism.

As a model for Christian holiness, Merton was far from perfect. In fact he took pains to distance himself from his early, more pious writings, and insisted on his right not to be turned into a myth for Catholic school children. He was a restless monk, and often chafed against his vows of stability and obedience. In 1966, during a hospital stay in Louisville, Ky., he fell in love with a young student nurse, and for some six months they had a kind of clandestine affair.

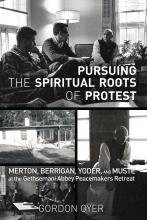

IN NOVEMBER 1964, as the long Cold War heated up again, this time in Vietnam, Trappist monk Thomas Merton set forth a koan to 14 peacemakers: “By what right do Christians protest?” For three days, these activists and theologians—famously uniting Catholic and Protestant faith traditions—met with Merton in the Kentucky hills, grappling with how and why Christians should resist the violence of war.

Historian Gordon Oyer has re-created this meeting so pivotal to the peace movement and—most important—assessed its meaning for our time. The historic retreat is meticulously sourced with detailed textual analysis of the presenters at the retreat and the writers who influenced them. Particularly impressive is the lucid summary of the era and the delicacy and respect with which the author treats cultural and doctrinal differences among the participants.

Ecumenism in peace work is thankfully common today, but in the early ’60s the blending of faith traditions at the retreat was groundbreaking. Even more revolutionary were the two Masses the group celebrated together, with Jesuit priest Dan Berrigan presiding, everyone in the group receiving communion, and John Howard Yoder, a Mennonite theologian, preaching at the second liturgy. (Both practices were proscribed at the time.)

Attendees included Phil Berrigan, later one of the creators of the Plowshares actions for nuclear disarmament, and A.J. Muste, dean of the U.S. peace movement at the time, with years of experience in War Resisters League, the Committee for Nonviolent Action, and the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). FOR’s Paul Peachey and John Heidbrink were instrumental in initiating and organizing the retreat, although neither of them could attend in the end. (Neither could two other invitees—Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King Jr.)

Don’t sing love songs, you’ll wake my mother

She’s sleeping here right by my side

And in her right hand a silver dagger,

She says that I can’t be your bride.

— from “Silver Dagger” by Joan Baez

It was their song — the young, winsome brunette and her silver-pated lover with the sparkly eyes.

“All the love and all the death in me are at the moment wound up in Joan Baez’s ‘Silver Dagger,’” the man wrote to his lady love in 1966. “I can’t get it out of my head, day or night. I am obsessed with it. My whole being is saturated with it. The song is myself — and yourself for me, in a way.”

He yearned for her. He was heartbroken. And he was Thomas Merton — the Trappist monk, celebrated author, and perhaps most influential American Catholic of the 20th century.

It’s a chapter of the thoroughly modern mystic’s life that is no secret to his legions of fans, detractors, and scholars of his prolific work, including the best-selling autobiography, The Seven-Storey Mountain.

Now Merton’s complex love life is the subject of a forthcoming feature film, The Divine Comedy of Thomas Merton.

Ah, the life of the church. So many arguments, so little time.

The list of subjects about which the saints disagree is seemingly endless, encompassing both the profound and the woefully mundane.

The ordination of women. The proper role of religion in politics. Climate change. Homosexuality and same-sex unions. Pre-, Post-, or A-millennialism. Biblical translation. Gender pronouns for God. How best to aid the poorest of the poor. How best to support the sanctity of marriage. Hell. Heaven. Baptism. Which brand of fair-trade coffee to serve in the fellowship hall. The use of “trespass/es” or “debts/debtors” in reciting the Lord’s Prayer. Whether to use wafers, pita, home-baked organic wheat, gluten-free or bagels at the communion table. What color to paint the narthex.

It should come as no surprise to most Christians that the world outside the church looking in sees it rife with conflict, bickering, arguments and castigation — of the “unbeliever” and fellow believers alike.

Frankly, it also should come as no surprise to the rest of the world that the church — by virtue of being a community of humans — naturally would have such disagreements and discord.

During Lent I occasionally choose a gospel companion to guide me through the season. I slip in behind one character or another in the Passion narrative and walk with them on the road to Jerusalem. One year it was Mary of Magdala. Another, Claudia, wife of Pontius Pilate.

This year I was drawn to Mark’s “certain young man”—the one who flees naked from the violence in the Garden of Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives (14:51-52), leaving behind his linen cloth.

Scholars vehemently disagree about who this young man was. Many deduce that it’s the writer of Mark’s gospel inserting himself into the story. Others say he is reminiscent of King David fleeing from Absalom on the the Mount of Olives. Or that he foreshadows the “young man” in a white robe who will meet the women at Jesus’ tomb.

Whoever he was, in the midst of an encounter with violence, this “certain young man” lost what thin protection he had and fled into the night, into the selva oscura, as Dante calls it, those “dark woods.” Toward what, we do not know.

AS THE HUMAN soul matures, we are confronted with moments that force us to let go of yet another thin veil of self-delusion. The “right road,” the moral high ground, sinks into a thicket of gray.

Singer-songwriter Denison Witmer’s 2005 album Are you a Dreamer? was part of the soundtrack of my adolescence — his calm voice a sonic companion as I navigated the choppy waters of high school insecurities; his complex fingerpicking acoustic guitar style a mentor as I learned to play and write my own music. Witmer’s soulful voice, thoughtful lyrics and inimitable style (some critics have called it “neo-folk” a la Cat Stevens or Nick Drake), has stuck with me for years. Just a snippet of his lyrics or melody can transport me back to precisely where I was when I first heard them, a younger me dreaming of who I might become.

When Witmer’s latest tour brought him through Washington, D.C. last month, I caught up with him backstage before his gig at the Sixth and I Historic Synagogue. We talked in the artist lounge and sound check stage, before venturing out for a couple of veggie wraps while exploring a variety of subjects from music and family to saints and beer. And we even managed to persuade him to play a couple of songs for us, which we’ve captured here on video for you. (You’re welcome.)

"Be anything you want. Be madmen, drunks, and bastards of every shape and form. But at all costs avoid one thing: success."

- Thomas Merton

As my extended family gathered around the Thanksgiving dinner table before the market crash in 2008, conversation with cousins flowed about friends making big money with technology start-ups: "more, more; faster, faster; bigger, bigger."

A hail of laughter greeted me when I quietly muttered that my ambition was, "poorer, poorer; slower, slower; smaller, smaller."

When Sojourners started in 1970, I was 23 years old. Seven young seminary students pooled $100 each and used an old typesetter that we rented for $25 a night above a noisy bar to print 20,000 copies of the first Post-American.

We took the bundles in our trucks and cars to student unions in college campuses across the country, and began collecting subscriptions in a shoebox kept in one of our rooms.

For more than a decade we lived with a common economic pot and allowed ourselves $5 a month for personal spending. The highest-paid staff person was a young woman from a neighborhood family who wanted an evening cleaning job.

I attended a basketball game this winter at the University of Maryland, accompanied by an intern at my workplace, a man in his twenties. For much of the game, we chatted about everything from politics to how North Carolina is far superior to Duke in all the ways that really matter (on the court, of course). During the conversation, between glances at the game, my colleague maintained steady eye contact … with his smart phone.