prophetic preaching

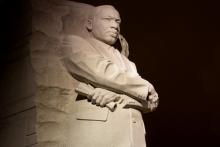

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. did not initiate black prophetic preaching; he was, rather, initiated into it. Rev. Kenyatta Gilbert’s A Pursued Justice: Black Preaching from the Great Migration to Civil Rights is a theological origin story about the distinctive rhetorical tradition that is black prophetic preaching.

The text begins by naming the social crisis of the Great Migration—shorthand for a massive demographic shift of 1.5 million African Americans from the South to the North between 1916 to 1940—as an essential context for understanding black prophetic preaching. This tradition of Christian proclamation—which Gilbert calls “exodus preaching”—is framed in the context of black pastors seeking to respond theologically to the pressures of injustice, prejudice, and segregation that black migrant workers navigated in Northern urban communities in the inter-war period. Of special note, Gilbert surfaces the social gospel tradition of African-American clerics who, unlike white social gospel leaders Walter Rauschenbusch, Josiah Strong, Washington Gladden, and others, demonstrated a desire to not only build institutional churches that confronted industrial evils but also to address systemic issues of lynching, police brutality, and so on.

While the entire book makes an important contribution to the study and practice of preaching, the third chapter, in particular, sparkles with insight. Within it, Gilbert marshals a solid cast of intellectuals—including Paulo Freire and Zora Neale Hurston—to land on a four-part definition of prophetic preaching. He contends that prophetic preaching unmasks systemic evil, remains hopeful in difficult situations, aids listeners in naming their own reality, and displays a will to adorn. The criterion of adornment—with patient attention to aesthetic categories of beauty, vision, and desire—is some of the most creative theological writing, in any genre, that you are likely to read. On a practical level, the definition provides a yardstick against which working preachers and homiletics faculty can assess the strength of contemporary pulpit work.

THE WORLD INTO WHICH we preachers cast our voices is already the world claimed, sought, and being reclaimed by Christ. For a white preacher to risk talk about race is an act of faith in the transformative resourcefulness of the Trinity. When it comes to the great divine-human contest with our sin, including our sin of racism, God will have the last word: “Come to me” conjoined with “Follow me.”

While preaching can’t do everything, God has chosen preaching as weapon of choice in the divine invasion and reclamation of creation. Theologian Richard Lischer says that Martin Luther King Jr. “believed that the preached Word performs a sustaining function for all who are oppressed, and a corrective function for all who know the truth but lead disordered lives. He also believed that the Word of God possesses the power to change hearts of stone.”

Preaching is one of the means through which God defeats our natural narcissism.

Theology, not anthropology

Much of my church family wallows in the mire of moral, therapeutic deism, a “god” whom the modern world has robbed of all agency. Ta-Nehisi Coates begins his riveting Between the World and Me by announcing that he is an atheist. Between the World and Me is an honest but brutal, sorrowing, eloquent, hopeless lament for the intractability of American racism. Coates castigates those African Americans who speak of hope and forgiveness.

I AM Nancy Hastings Sehested, messenger from Prescott Memorial Baptist Church, pastor of Prescott Memorial Baptist Church, and servant of our Lord Jesus Christ. I am a full-blooded Southern Baptist. My mother is a Baptist deacon. My grandfather was a Southern Baptist minister for 70 of his 93 years. My dad is a retired Southern Baptist minister with 50 years of ordained ministry. ...

By what authority do I preach? ... It is not a new question. It is a question that was asked of our Lord Jesus Christ on a number of occasions. He had not the authority of the religious establishment, nor the authority of the state, but the authority of none other than the Holy Spirit that moved in his midst.

And so, by what authority do I preach and bear witness to my faith? ... By the authority of the Lordship of Jesus Christ, who did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, becoming a servant. And following in his footsteps, as a servant of Jesus Christ, who took the towel and the basin of water and exemplified the kind of servanthood that each one of us is called to live under, I found a towel with my name on it. And who was it that taught me this wonderful freedom of the Spirit? My Sunday school teachers. My pastor. My Southern Baptist church, who nurtured me and said, “God calls each one of us, so listen!” And so I listened.

Last fall, on a Sunday afternoon, as I walked out of the church, a young man tugged on my Franciscan habit. It was Miguel, a member of our Latino choir.

“Father,” he said, “please, pray for the people of my home parish back in El Salvador, especially for one of the priests who has received death threats.”

Startled, I asked: “What is happening there?"

“These priests are organizing against the multinational companies,” he said. “The companies are looking for gold. What will be left for our people? Only poisoned water, a wasteland, and death.”

A few weeks later, I had another similar conversation with a group from Guatemala. Theirs was a similar tale of how indigenous communities were being threatened by mining projects.

As a Catholic and a member of the Franciscan Order, I believe that we are called to “read the signs of the times” and to listen to the cry of the poor and the “groaning” of God’s Creation.

As the Christmas season draws to a close, I am reminded of the star that directed the three wise men away from their homeland and into the foreign but welcome presence of baby Jesus. Perhaps this reminds us all that the Divine is constantly moving us into new territory, as stars of all sorts continue to illuminate our path and reset our orientation. The New Year is a wonderful time to search the skies again and see where God is leading us – to check the progress of Church, society, and self, and also see when a new course needs charting. Such a pause allows us to live in our prophetic selves.

As you plan this year – and especially the month of February – remember that the role of a prophet is to, when necessary, provide faithful interruptions or disturbances to the fragile balance of our complex (and often incomplete) frameworks. (That is ONE role of the prophet, anyway). At any given point in the history of civilization we find each of our systems broken – by definition – because humans and not gods have created them.

And while these machinations and paradigms were created to solve society’s most pressing problems and questions, they often serve as coping mechanisms, “band-aids,” and gas canisters that fuel us only to our next checkpoint. You can think of many of these unfulfilled solutions, none of them mutually exclusive: they plague all the sectors of our common life.

The month of February sheds light on one in particular. In the quest for racial justice, we have reached not the finish line but a checkpoint, and we need more prophets.