Prison

Leslie Zukor was a 19-year-old student at Reed College studying prison rehabilitation programs when something jumped out at her.

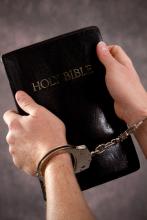

“Not all prisoners are religious, and I wanted them to know that to turn your life around and be a good and productive member of society does not require a belief in God,” she said. “I just thought, wow, it is time to see about getting other perspectives in there.” While there were programs tackling drug abuse, physical and sexual abuse, technical training, and more, all of them were offered by faith-based organizations. Where were the options for those behind bars who are atheists, like her?

So Zukor launched the Freethought Books Project, collecting books about atheism, humanism, and science and sending them to interested prisoners. She estimates that since her first book drive in 2005, she has given out 2,300 books, magazines, and newspapers to perhaps hundreds of prisoners across the country.

SHORTLY AFTER his 1983 appointment as archbishop of San Salvador during the Salvadoran civil war, Arturo Rivera y Damas traveled to the United States. Rivera succeeded Archbishop Óscar Romero, who was martyred for his outspoken condemnation of the war. I asked a Maryknoll sister—who lost three community members, killed by the Salvadoran death squads—to assess Rivera’s comments to the U.S. media. “He does not have the gift of martyrdom,” she said.

That comment gives perspective to the efforts of nonviolent peace activists in the U.S., many of whom have risked their freedom, usually for short stints, as a consequence of civil disobedience. In Crossing the Line: Nonviolent Resisters Speak Out for Peace, Rosalie G. Riegle chronicles the action-to-court-to-jail-and-prison journeys of some of the last century’s most committed pacifists. While a few told harrowing stories, for the vast majority the consequences fell far short of martyrdom. This is not to belittle their efforts, but rather to beg the question: Why do so few Christians resist the violence and war-making of the U.S. government?

Riegle’s well-done compilation of 65 oral histories might prompt more people to step into the fray. To date, hundreds of U.S. pacifists have served hundreds of years, mostly in federal prison, for crossing lines, burning draft cards and draft files, and hammering on the weapons of war. At press time, three Catholic pacifists known as the Transform Now Plowshares—Sister Megan Rice, Greg Boertje-Obed (interviewed in Riegle’s book), and Michael Walli—await a January sentencing for federal felony charges stemming from cutting fences and hammering at the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tenn.

I recently watched Eugene Jarecki’s remarkable documentary, The House I Live In, which is about the American ‘war on drugs’ and the burgeoning prison population it engendered and continues to engender.

Rarely do I find myself murmuring and tsk-tsking during a movie, but this one was highly affecting — an intimate look at how history, racism, economics, and politics have created a system that no one is proud of and no one really likes. Even the cops and prison guards who claim to love their jobs express unease with the human suffering and unbalanced scales of justice that lead to it.

One particular story has stayed with me.

A man named Kevin Ott was found in possession of a small envelope of meth; prior to that he’d been arrested twice, again for possessing small amounts of illegal drugs (meth and marijuana).

He’s been in prison for seventeen years. And he will be there until he dies: Ott is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole. Because he was a three-time offender, his state’s mandatory sentencing laws required that he be put away for life.

As we prepare for the coming of Christ, the third Sunday of advent is celebrated in joy. As followers of Christ, it is reasonable to be exuberant about the birth of our Savior. The amount of happiness that can seep from the soul in response to a virgin birth, a perfect baby boy, and an adorable scene of livestock and shepherds befriending God’s family is immeasurable. Christmas music, Christmas decorations, and yes, even Christmas presents add to the joy and never fail to put a smile on my face.

This past weekend, as I tried to reflect on what it means to be joyful in Christ, my heart was temporarily hardened as I attended a Reentry Arts & Information Fair for returning citizens. I helped host a table for Becoming Church and their Why We Can’t Wait initiative.

“Lord, when were you in prison?” we’ll ask of you one day;

And when did we go visit you, and listen well, and pray?

And when did we show mercy there (as we need mercy, too)?

As we love those in prison, Lord, we show our love to you!

When you taught love of neighbor, had you heard in your time

Of one who lay beside the road, a victim of a crime?

The neighbor that you said was good brought help and wholeness, too;

May we help those who hurt so much from crimes that others do.

Still Shining

David Hilfiker is a retired inner-city physician and writer on poverty and politics who has Alzheimer’s. He writes about his experience, with the hope of helping “dispel some of the fear and embarrassment” that surrounds this disease, on his blog “Watching the Lights Go Out.” www.davidhilfiker.blogspot.com

Transported

Laura Mvula is a British, classically trained musician, songwriter, and former choir director whose debut album,Sing to the Moon,is a lush fusion of soul, jazz, gospel, and pop. While not overtly “about” faith, her arrangements are imbued with spiritual longing and visions of beauty. Columbia

I remember the first time I ever got straight A’s. It was also the last time.

I was in Mrs. Becker’s 4th grade class at John Story Jenks School in Philadelphia. I was always good at reading, I LOVED science projects, and art class was fun — but math? Ugh. Math was my nemesis. In 4thgrade the times tables felt as insurmountable as that dang rope everybody else could whiz up and down in gym class. I just couldn’t figure it out. In fact, to this day, I haven’t figured the rope.

So, my father became my times tables drill sergeant and resorted to straight memorization tactics, making me write each one 10 times. Then he sat across from me at the dining room table and drilled me on the times tables until I said them in my sleep. It was brutal … and oddly, one of the fondest memories of my elementary school years. Not only did I master multiplication, but I also learned something much more important. When my report card came back that quarter with straight A’s, I learned that I could learn!

My dad used to tell a joke from the pulpit, back when “damn” was a much stronger word in evangelical/fundamentalist circles than it is now.

It went roughly like this:

“Millions of people die every day from preventable causes without ever having heard about Jesus’ love, and most of you don’t give a damn, and most of you are probably more worried about the fact that I said ‘damn’ than about the fact that millions of people die daily from preventable causes without ever having heard about Jesus’ love.”

I have a new post up at her.meneutics, Christianity Today’s women’s blog that, quite frankly, I don’t expect too many people to read.

It’s about how it’s perfectly legal in most states to shackle pregnant women while they are in labor.

IN "SILENCE FOR GAZA,” Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish captures the contradictions of the coastal enclave, describing it alternately as “ugly, impoverished, miserable,” and “the most beautiful, the purest and richest among us.” Darwish’s antonyms evoke Gaza’s crushing conditions and resilient residents, exemplars of sumud, an Arabic word roughly translated as “steadfast perseverance”—a fundamental form of Palestinian resistance. Darwish’s poem also states that Gaza “did not believe that it was material for media. It did not prepare for cameras and did not put smiling paste on its face.” And yet every person, every story, every image of Gaza illustrates this persistent paradox of a land at once ugly and beautiful.

“I DON’T KNOW why they targeted us. No rockets were fired from our neighborhood,” says citrus farmer Yusuf Jilal Arafat, whose 5-year-old daughter Runan was killed when Israeli warplanes bombed their home. Arafat’s wife, four months pregnant, and their 8-year-old son were found alive in the rubble. His surviving children now suffer from frequent panic attacks at night. Many of Arafat’s trees were destroyed by the bombs, and the ground is covered with oranges now in various stages of decay. Rumors of contamination by Israeli weapons may hurt the sales of his crop, but he will still harvest. The family is living with Arafat’s father-in-law until they can rebuild.

Rebuilding under Israeli import restrictions is no simple task, so salvaging existing materials remains a vital practice—albeit risky, according to structural engineers. But ingenuity-by-necessity is constantly on display in Gaza, whether it’s recovering crushed stone from beneath ruined highways, straightening steel rebar from bombed-out buildings, or pulverizing concrete for reuse in new (but weaker) blocks.

THE UNITED STATES has more than 2.3 million prisoners, a higher number than any other country. How did we become the world’s leading jailer? One of the main culprits: Mandatory sentences.

Visiting those in prison and giving Christmas gifts to children of incarcerated parents are only two steps toward fulfilling Jesus’ command to care for the “least of these” (Matthew 25). It’s time for the church to get serious about criminal sentencing reform—particularly, the reform of mandatory minimum sentencing laws, which lock up so many people for so long with so little benefit to society.

The explosion in state and federal prison populations and costs began in the 1980s with the so-called war on drugs. Lengthy mandatory minimum prison sentences passed by lawmakers are the primary weapon in that “war.” Judges have no choice but to apply these automatic, non-negotiable sentences of five, 10, or 20 years or even life in prison without parole. Whether the punishment actually fits the crime or the offender, protects the public, or leads to rehabilitation is irrelevant.

The results are unsurprising: irrational sentences, $80 billion annually in prison costs, and horrifically overcrowded prisons. States as varied as Georgia, New York, Delaware, South Carolina, California, and Michigan have confronted the reality of unsustainable prison budgets by repealing mandatory minimum sentences or creating “safety valve” exceptions that let judges go below the mandated punishment if the facts and circumstances warrant it. During this wave of reforms, crime has dropped to historic lows.

A radio documentary with Susan Burton, Michelle Alexander, and five residents of A New Way of Life Reentry Project.

Bio: Founder of A New Way of Life Reentry Project in California, which has provided housing and support for more than 500 formerly incarcerated women. anewwayoflife.org

1. What motivated you to start A New Way of Life in 1998?

Through the kindness of a special person, I was able to access treatment services in Santa Monica [Calif.] after the sixth and final time I was released from prison. This was a new phenomenon for me. I am originally from South Los Angeles, and I was amazed that such resources were available in this more-affluent part of the city. I began to wonder why those same resources were not available in my home community—an area so heavily impacted by the “war on drugs.” I knew the need was desperate, and I wanted to bring those resources to South L.A. My work since then has been, and continues to be, a work of faith. I step out in faith, and God shows up.

I can’t think of a way that it’s good for anyone. The current system treats everyone inhumanely. It puts them into the category of slaves. It exploits their families. It kills their hopes and dreams. Our mission is to address the needs of people who have been negatively and cruelly treated by the criminal justice system and to restore their hopes and dreams by treating them with dignity and respect.

CLAREMONT, Calif. — Last Sunday, Timothy Murphy began a fast of solidarity with the Guantanamo inmates who are on a hunger strike to protest their indefinite detention. As one of our Ph.D. students and an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Timothy felt spiritually called to the hunger strike. He is drinking water and nothing else.

Timothy intends to continue as long as he is able, or until the Obama administration begins taking action to address the prisoners’ legitimate grievances, including deliberate steps to find homes for the 86 prisoners who have been cleared for release. Timothy says he would be happy to stop the fast tomorrow if the administration indicated that it was taking steps to do this.

I, like Timothy, believe this is a basic human rights issue for the prisoners. I also believe that it is critical for the health of our nation’s collective soul and integrity to get it resolved. Timothy’s deep commitment inspired me, so I decided to join him, but in a more limited fast: I am fasting three days this week, and every Thursday hereafter, until steps are taken to resolve the Guantanamo issues.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world — about 1.6 million people in 2010. Mass incarceration in our country is a problem, one that too often serves to line the pockets of for-profit prisons while tearing families apart and targeting people of color disproportionately.

Beyond Bars — a project to curb mass incarceration in the U.S. — produced the following video that puts faces to that problem. Watch the moving video below, and ask yourself the question: would putting them in prison serve the common good?

TODAY, Greg Bright, 56, sits on the cement porch of his yellow clapboard house in New Orleans' 7th Ward and rests his hand on the head of his yellow dog, Q. It is 2012, and he often finds himself musing over the notion of time—time past, time lost, time wasted. "It feels like a minute since I been out here," he says. It took some time to adjust to life on the outside, he admits, and once, on a dark rainy morning as he found himself biking seven miles in the rain to his miserable job working the line in a chicken plant in Mississippi, he felt real despair—just recognizing that he was 47 years old and had never owned a car. He tried hard to dismiss the sobering thought that, arrested at age 20 and doing 27 years of time, he'd been "seven more years in prison than I was on the streets." Sometimes, he says, "it's little things like that" that really threaten to drag him down into sorrow.

So he chose to do something that both keeps those wasted years fresh in his memory yet also mitigates the sense of powerlessness he sometimes feels. He helps to educate others in the hopes that his story will spur reforms. He is not an educated man—his formal schooling stopped in sixth grade—but he is one of dozens and dozens of ex-cons who form a vital link in the post-Katrina criminal justice reform efforts through various organizations such as Resurrection After Exoneration, a holistic reentry program for ex-offenders, and Innocence Project New Orleans. Greg tells his story to students, activists, politicians, church groups, friends, strangers—anybody with time to spare and an inclination to listen—doggedly putting a face on an abstract idea, injustice.

ONE EVENING LAST July, I walked up to the Port Everglades U.S. border checkpoint in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., to intentionally turn myself in to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. My mission: to get into Broward Transitional Center, a privately run U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention facility, to expose the stories of those held there. It's categorized by ICE as a model facility. But as I witnessed firsthand, it is nothing short of a prison where, as in the other 250 immigration prisons across the U.S., immigrants are arbitrarily held and exposed to all kinds of human rights abuses.

The total number of undocumented immigrants detained in the U.S. each year is sky-high—ICE detained 429,247 people in 2011 alone. In August 2011, the administration announced that it would focus its deportation efforts on people with criminal records. "Obama is only deporting gangbangers and felons," established immigrant advocacy organizations said. "He's our guy for immigration reform!"

But that is far from true. In my work with the National Immigrant Youth Alliance (NIYA), I keep hearing the real stories of immigrant prisoners and the loved ones from whom they're torn.

Getting detained was part of a strategy of civil disobedience that fellow activists and I have been pursuing since 2010: In order to pressure ICE and the government, we have to put ourselves on the line. I was one of two Youth Alliance activists who sought to infiltrate the Broward Center to find out the inside story. We also set up a telephone hotline, funded by donations from the community, to take calls from people detained in the center.

What struck me as he spoke was the sheer human potential of this my client, wasted. That matters for all of us because of an unflinching Scriptural text about how we can enter the kingdom of God: “for I was hungry and you gave me food; I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink; I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was sick and you took care of me. I was in prison and you visited me….just as you did it to the least of those who are members of my family, you did it to me.” (Matt. 25:35-40)

That’s the test. Not beliefs or intentions. Actions.

Specific actions: Jesus tells us to visit people considered the worst among us, those accused of breaking the law.

It’s not just innocent prisoners we are to see; it’s prisoners. They are all Jesus.

Former Penn State Football Coach Jerry Sandusky has been sentenced to no fewer than 30 years in prison, and up to 60 years. Given Sandusky's age, 68, the ruling is basically a life sentence.

From NBC News:

"Sandusky, who was defensive coordinator and for many years the presumed heir-apparent to legendary Penn State football coach Joe Paterno, could have faced as long as 400 years for his convictions on 45 counts of child sexual abuse, but at age 68, he is unlikely ever to leave prison, assuming he loses any appeals."

Yesterday, Sandusky released an audio statement maintaining his innocence and lashing out at his offenders.

TORONTO — The Canadian government is canceling the contracts of all non-Christian chaplains at federal prisons.

By next spring, Muslim, Jewish, Sikh and other non-Christian inmates will be expected to turn to Christian prison chaplains for religious counsel and guidance.

In an email to reporters on Oct. 4, the office of Public Safety Minister Vic Toews, who is responsible for Canada's federal penitentiaries, said the government "strongly supports the freedom of religion for all Canadians, including prisoners."