pop culture

EVER SINCE I was little, my imagination has been shaped by superhero worlds, lore, and comic and animated adaptations. And while more “realistic” adaptations are the trend on the big screen, what enthralled me about characters such as Batman wasn’t that I thought he could be real; I was tuned instead to the ethos behind the caped crusader.

Superhero stories often seem limitless. At their best, they stretch the imagination to ask what type of world we want to exist and what it would take to get us there, while acknowledging hardships along the way.

Recently, I began a rewatch of the DC Animated Universe: TV shows, feature films, and shorts that aired mainly from 1992 to 2006. These shows were the first to capture my attention and shape my imagination. Batman: The Animated Series was my first love, with Kevin Conroy’s Batman and Mark Hamill’s Joker seared into my consciousness. As I watched, I made a particular note about the moral imagination of these shows: Superheroes in these shows don’t just refuse to kill — a theme recurring across superhero worlds — they refuse to even let anyone die.

Take Season 1, Episode 11 (S1 E11) of Superman: The Animated Series: Lex Luthor’s weapons factory is about to explode, with spilled molten metal splashing about. Lana Lang is hanging by a thread above certain death; so is Lex Luthor, who unintentionally caused this mess in his attempt to kill Superman. But then, at the last moment, Superman bursts forth from under the molten waves, crashing out of the top of the factory just before it explodes, with Lana in one arm and the villain in the other.

It’s a scene that strains credulity. There’s an improbability of timing, a lack of “logic” in doubling back for the person trying to kill you, and the storyteller’s refusal to explain how Superman managed to save the villain. But what’s key here is the insistence, and flaunting, that Superman would save the villain. It doesn’t need an explanation; it’s assumed.

For a while, I was paying attention to how the writers made this subtext believable. Superman saves some villains in hopes they can be rehabilitated, others because they are being used by larger, more villainous characters. Why? The simple answer is that these were shows for families and children. The same reason the comic book’s “League of Assassins” became the TV show’s “Society of Shadows” and villains set out to “destroy” rather than “kill” heroes.

But this death-resisting subtext becomes dialogue in S2 E9 of Superman: The Animated Series when some kids plead with Metallo, a villain disguised as a hero, to save Lois Lane from an exploding volcano. “Superman wouldn’t let anyone die, no matter how bad they were,” the kids protest. “I’m not Superman,” Metallo retorts.

POPULAR CULTURE PLAYS an important role in shaping our view of the possible. Ta-Nehisi Coates, author of Between the World and Me, for years wrote Marvel’s Black Panther and Captain America comics. “I think we don’t always realize the extent to which the culture actually interacts with politics,” Coates said on Ezra Klein’s podcast. “I could advocate for all of the policies in the world ... but it really, really occurred to me that there’s a generation that is being formed right now that’s deciding what they will allow to be possible, what they will be capable of imagining. And the root of that isn’t necessarily the kind of journalism that I love that I was doing, the root of that is the stories we tell.”

In this issue, sojo.net associate news editor Mitchell Atencio looks at some of those stories — in particular, superhero comics — and explores what is not being told, and how pop culture often avoids grappling with the way our country approaches issues such as policing and incarceration. That failure has consequences far beyond the DC and Marvel universes.

Copaganda refers to any piece of media that portrays police as a necessary social institution. While this can include viral videos of police chatting with neighborhood kids or doing lip-sync battles, the most pervasive examples of copaganda are found in pop culture.

Game of Thrones, the engrossing, sometimes disturbing, always exciting TV series returns for a sixth season Sunday night on HBO. The network is not releasing screeners, so it’s anybody’s guess what’s going to happen. But one thing you can bet on — the television show, like the books by George R.R. Martin they are based on, involve storylines with religious elements. Considering where some of those stories left off, religion may come further to the fore in the new season. Here’s a primer on a few of the religions of Westeros, the imagined, medieval-inflected world of Game of Thrones.

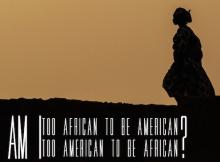

Being Between

The documentary film Am I: Too African to be American or Too American to be African? focuses on young African women who live in the U.S. and West Africa but identify with both cultures. How do they work out unique twists in the issues of race, complexion, gender, and family heritage?

Revealing the Word

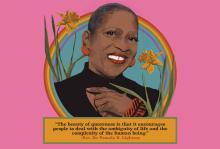

Nyasha Junior, assistant professor of Hebrew Bible at Temple University, has written An Introduction to Womanist Biblical Interpretation, an accessible and forward-looking guide to African-American women’s contributions to biblical scholarship. WJK Press

Dear Missionaries,

I like to tell people I’m a missionary convert, because I wear this genesis of my faith journey proudly, like a badge of honor. I heard the story of Jesus from your lips, sang the songs of worship in your language, and prayed for the concerns in your heart. You taught me how to be Christian.

I learned from your lavish generosity and boundless love and affection. I also learned how to do Christmas. One day in my freshman year of high school, I asked my Chinese parents if we could find a Christmas tree. This was before Christmas became commercialized in Taiwan, so all I could find was a tacky, tiny, plastic tree, which I set up delightfully in the corner of our living room. I arranged neatly wrapped fake presents under my wannabe tree and meticulously set up some lights. I longed for that warm feeling I felt in your homes, the atmosphere I saw in American movies. I wanted to be like you; if only I could have convinced my parents to do Christmas like you did, with gifts, candles, and prayers.

Little did I know your celebrations were crippled by your overseas living because, like me, you also could only find dinky little plastic trees. When I visited your home country, I saw the full potential of CHRISTMAS unleashed, with real trees as tall as houses and white lights, icicle lights, flashing lights, lights shaped like reindeer, elaborate nativity sets, and ridiculous amounts of presents and candy. I thought, wow, is this how the Christians do Christmas?

The Jesus of pop culture is multiethnic and well-traveled, pious and irreverent, singing and silent. A fictional portrayal that is blasphemy to one viewer is sacred to another. The diversity of Jesus’ depictions reflects the diversity of the pop culture audience. Most recently, another fictional Jesus has appeared in Compton, smoking weed and promoting “black-Latin” reconciliation in the new comedy Black Jesus. The sitcom presents a Jesus who uses at times crude language to ultimately promote a consistent gospel message of love. While this Jesus “shares in the pleasures” of his largely poor, African-American community, “he also challenges their prejudices, violence, and self-seeking.” Read more in Danny Duncan Collum’s “The Christ of Compton” (Sojourners, November 2014).

Check out this list to read about five portrayals of Jesus in recent pop culture history.

1. Lion Jesus

In The Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis sets up a less than subtle allegory of Jesus in the form of a lion named Aslan. Aslan transforms a void into a world through song. He welcomes children. He dies and comes back to life. But still, he is a lion, fierce and elusive, helping to convey both the intimidating power and the radical love of Jesus.

“‘Safe?’ said Mr. Beaver; ‘don’t you hear what Mrs. Beaver tells you? Who said anything about safe? ‘Course [Aslan] isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.’” –The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe (1950)

My wife and I are attending our denomination's national assembly in Orlando this week. Last night, we went to a retirement party for one of her mentors. As a group of ministers tends to do, they concluded by gathering around, laying their hands on, and offering him a prayer of blessing. Then the group spontaneously broke out into a round of song that went on for a few minutes. It was both beautiful and touching.

The wait staff, however, wasn’t quite sure how to take it.

"Wow," one bartender said," that's amazing. You guys can all really sing."

Amy just smiled.

“That's church," she said.

ONE SUNDAY EVENING during high school, friends from my Mennonite church and I drove around Lancaster County, Pa., stealing mattresses. Bored by too many evenings of roller skating and Truth or Dare, we, like teenagers everywhere, landed on thievery as the solution to adolescent ennui. Having found out which of our friends were away from home, we showed up at their houses, told their parents about our prank, and swore them to secrecy. Then we clomped up narrow staircases to their sons’ and daughters’ bedrooms and wrestled mattresses back downstairs and onto the bed of a pickup truck. Just before our getaways, we left notes on our friends’ dressers, signed with what we thought was a most clever alias: “The Mennonite Mafia.”

We had no idea that 25 years later, Amish Mafia would be a blockbuster reality show, its first episode attracting 10 times more viewers than there are Amish people. Had you told us then that a bunch of Amish and Mennonite kids growing up a few miles away would someday parlay boredom-induced shenanigans into a hit cable TV series, I don’t know whether we would have been flattered or jealous. Kate Stoltzfus? Rebecca Byler? Lebanon Levi? People with names like these—our “plain-dressing” Amish neighbors and the more conservative Mennonite kids we went to school with—were the butt of our jokes, not the cynosures of popular culture.

Only a few decades after we and our families exited the conspicuous conservatism of plain Anabaptism, mass culture is flocking toward it. From Amish-themed reality TV shows to Christian romance novels with Amish characters and settings, the media have finally landed the lucrative Amish account, although the furniture industry and “Weird Al” Yankovic’s “Amish Paradise” got there first. Americans’ enthrallment with the Amish—and schadenfreude about their sometimes wayward youth—has rarely been more intense.

This Christmas, for the spirituality-and-pop-culture enthusiasts on your gifting list, consider the following: Be kind and rewind.

Give them the gift that keeps on giving ... long after the series has been cancelled.

Rev. The Vicar of Dibley. Saving Grace. Davey and Goliath. Pushing Daisies. Six Feet Under. The Book of Daniel. Lie to me. Lost. And Northern Exposure.

“In order to serve our world," Bono once said, "we must betray it."

I’ve always wanted to change the world. I’m inspired by stories of people who have left their fingerprints on the very face of culture. I want to be a historymaker. I want to be one who people remember as a person who revolutionized her world.

As noble as this sounds, I’m afraid that up until a few years ago, this has come from a very self-serving motivation. I truly did want to love people and make a difference for their benefit, but I also wanted the credit. Visions of winning a Nobel Prize danced through my mind; dreams of becoming the “woman of the year.” I’ve thought out speeches just in case.

I can’t believe I just admitted that to you. I must really like you.

I had to come to a broken place in order to be ready to bring about the change I so desired to initiate. You see, transformation, no matter how small or big, is never about us. It’s not about the recognition we will receive or about the merit badge that will feed your need for approval. No, it’s the most selfless thing we will ever do. We need to be trustworthy to lead such efforts.

All it takes is a heart that truly cares for others — that’s it. Once your eyes are off yourself, you become incredibly useful! What a thrill it is to add benefit to others and get no credit for it.

Step aside Reinhod Bieber — there’s a new 20th century philosopher/pop star in town: Justin Buber. That’s right, the Bieb’s popular songs and tweets and Martin Buber’s existential Jewish thought combine in a way that would have the renowned thinker pulling the hairs out of his mountain-man beard.

One of Buber’s notable contributions to modern Jewish thought centers around the distinction of I-Thou (a holistic, infinite relation shared between people or God) and the I-It (a disconnected objectified relation). But if you’re Justin Buber , it might look something like this:

“Tonight I’ma be with u, shawty with u. For the space between two beings is where God may occur.” - October 26, 2011