digital age

I WAS SITTING in a large auditorium full of market researchers. A speaker suggested that, by selling wrinkle cream, we were helping to make the world a better place because women would feel better about themselves. I looked around the room, thinking, “Is everyone buying into this? Do people really think this is true, or do they see that it’s just a corporate pep talk?”

I had worked in the world of international market research for nearly 10 years. Though there were a few moments like this one when something just didn’t feel right, in many ways I still didn’t see the issues I see so clearly now — marketing techniques are the air we breathe.

I eventually left my work in marketing to pursue a master’s in social justice and a doctorate in theological ethics. I began to investigate how marketing practices negatively impact how we live as human beings and how we think about marketing in the church. In contemporary society, we tend to view marketing techniques as neutral tools that can be applied in different contexts — whether for businesses, nonprofit fundraising, or church communication. But can we adapt tools that have been developed in the context of capitalistic profit maximization to the mission of the church? Are there fundamental differences in how the church views and relates to human beings?

I had worked in the world of international market research for nearly 10 years. Though there were a few moments like this one when something just didn’t feel right, in many ways I still didn’t see the issues I see so clearly now—marketing techniques are the air we breathe.

Ta-Nehisi Coates on the Obama administration’s decision to seek the death penalty for the Charleston shooter: “The hammer of criminal justice is the preferred tool of a society that has run out of ideas.”

2. At Baylor, the Real Story Isn’t Hypocrisy. It’s the Victims of Sexual Assault.

“... this is a story much larger than Ken Starr and Baylor. This story is about power, and money, and institutions that claim to be faith-based but refuse to stand for victims and against violence.”

Lives in the hands of algorithms—

“THE COMPUTER’S not the thing. It’s the thing that will get us to the thing,” intones Joe MacMillan (Lee Pace), the enigmatic visionary at the heart of AMC’s new techno-drama Halt and Catch Fire. Set in the early 1980s in Texas’ “Silicon Prairie,” the series chronicles a small, fictional software company that enters the personal computing fray. This is the age of IBM dominance and the improbability of an underdog company taking down the computer Goliath is the premise of the show.

HCF is a kind of origin myth: a drama that tries to capture the spirit and personalities that drove the personal computing revolution that reshaped the world we now inhabit. Across the cable universe, HBO offers another riff on the same theme set in the present day. Silicon Valley is a satirical send-up of startup culture and the boy-men who rule the northern California empire to which we are all in thrall. In tone and style it is the antithesis of the self-consciously serious HCF. But the two shows share a similar preoccupation with exploring the humans who make technology even more than the technology itself.

This is partially a necessity of good storytelling. Nothing slows down a story like having to explain technical expertise. At best you can get a few gags out of the science geek spewing unintelligible jargon to the bewildered “everyperson” (think Sheldon’s whole persona on The Big Bang Theory). But this narrative limitation also hints at the enigma both shows are trying to explore: Who are the people who understand the jargon and create the technology that defines our new digital age? What is the nature of this kind of power?

“I think it would be fun to run a newspaper.”

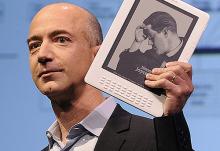

THE QUOTE IS from Charles Foster Kane, the character based on William Randolph Hearst in Orson Welles’ 1941 classic Citizen Kane. But it could have been Amazon kingpin Jeff Bezos this August when he bought The Washington Post. What can you get for the man who has everything? Maybe he’d like a newspaper to play with, preferably one with global political clout.

Unlike Charles Foster Kane or Rupert Murdoch, Bezos seems disinclined to monkey with the content of the Post’s coverage. His business interests may require certain government policy directions—i.e. free trade and no unions—but on those questions the Post is already with him. They differ on net neutrality (the concept that providers of internet access should not be able to discriminate against or give preference to specific internet service or content providers), so that will be one to watch. But Bezos comes to the Post saying he essentially agrees with the paper’s politics. In fact the Post’s reputation as a credible voice for corporate centrism seems to be a large part of what Bezos wants for his $250 million.

This may explain why Bezos, a titan of the rising digital world, would weigh himself down with an ancient “legacy” institution. It’s an old American story. When you get rich enough (Bezos’ fortune is estimated at $27 billion), you don’t want more money, you want power and respect. The same process played out with the robber barons in the last century. It’s just that today the evolution happens much faster. It took three generations for the Rockefellers to go from oil tycoons to philanthropists and politicians; contemporary barons such as Bezos and Bill Gates have made the switch within a couple of decades.

It’s exhilarating to realize that I’m getting more done in less time. I got up and took a walk around the church while back, feeling pretty satisfied that I had fulfilled all of my professional duties for the day. And here it was, more than an hour before I even have to go pick up the kids!

But then I had a moment beset with pangs of anxiety. Yes, at the moment I can answer emails faster with this little gadget than most people can muster a response. It puts me slightly ahead of the curve. But then I realized this advantage is only a temporary luxury. The efficiency that a new technology affords only works as long as the majority of people you come into contact with aren't yet using the same technology. Once they are, the entire conversation accelerates, and the expectations of everyone increase to at least reach the maximum limit of the new capability everyone has just recently acquired.