child

Diseases don't read, but they understand social contracts. They kill and maim the poorest and weakest among us first: pregnant women, people without air conditioning, people who have to store water outside in case of shortages, places where mosquitoes breed and grow and bite and viruses swarm the placenta and maim a growing baby's brain.

Pope Francis is expected to meet a young girl from Ohio who dreams of seeing the pontiff in person before she loses her eyesight, according to a Catholic organization that supports sick and disabled pilgrims. Five-year-old Lizzy Myers from Bellville, north of Columbus, suffers from an incurable genetic disease known as Usher syndrome, which leads to blindness and hearing loss.

After five days in the hospital, filled with overwhelming joy, paralyzing fear, and complete exhaustion in the wake of the birth of our twins, I finally found a moment to walk outside the florescent lights and sit under the bright moon. Sitting on a small patch of grass outside the hospital doors, the reality of being a father to four kids finally hit me. I was both overwhelmed and overjoyed by the gift and responsibility of raising four kids in a world so desperately in need of mustard seeds of hope that one day blossom into healing and beauty.

So as I sit in relative comfort and begin to dream big dreams for my kids, I am struck by the reality that most fathers around the globe are forced to welcome their kids into a world where there is no "ladder" to climb because it has been knocked out from under them by broken systems that are breaking people. A world where many kids are born into families fleeing violent persecution and being nursed on the trauma of war in battered refugee camps — places where the thought of hope is a distant second to simply fighting to survive. A world where one’s value is more closely associated with gender (male) than with the beautiful uniqueness inherent in every new life.

But this is also a world pregnant with possibilities. A world where former enemies move beyond their past, share tables, and begin to imagine a future together. A world where the blossoms of new life begin to sprout in the shadowy corners of forgotten neighborhoods. A world where the diversity of God’s kingdom begins to awaken our eyes and hearts to the new world God is making.

It is in this world — a world both beautiful and broken — that I offer this prayer over my four kids.

IN 1998, AWARD-WINNING writer Linda Lawrence Hunt and her husband, Jim, were forced to consider a question no parent wants to ask: How do you find meaning in life after losing your child?

Their 25-year-old daughter, Krista Hunt Ausland, had just died in a bus accident in Bolivia while volunteering with the Mennonite Central Committee.

“Your joys become more intense,” consoled a friend whose family had also lost a child.

This resonated with Linda, especially since Krista was known for her energy and enthusiasm. Linda and her husband, now retired professors of English and history at Whitworth University, had always encouraged Krista to travel and take part in community service, but even they were amazed by the intense joy Krista exuded serving as a school teacher in inner-city Tacoma, Wash., or volunteering in poor communities in Latin America. Writing about that joy might help to recover some of it in Linda’s own life, she thought.

Fifteen years later, Linda’s newest book is more than just an ode to a remarkably happy daughter. Pilgrimage through Loss: Pathways to Strength and Renewal after the Death of a Child is a collection of ideas and insight from more than 30 parents who decide in their darkest hours to “face grief in creative and intentional ways.” The book, which contains study questions at the end of each chapter and references new research on grief, is intended as a resource for grieving parents, as well as for those hoping to support them in the right ways and at the right times. “Closure is an illusion,” explains Linda, but she describes multiple examples of parents finding strength and even joy in sacred spaces and rituals, as well as in giving and receiving symbolic acts of kindness.

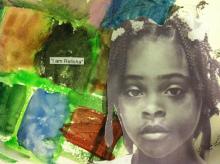

The first ominous sign that the Relisha Rudd case was slipping from the local Washington, D.C. imagination was when the police alert signs posted on the roads into the city had their messages changed, or were removed entirely.

For weeks after the news that the little eight-year-old girl was missing broke on March 19, the digital display boards had broadcast the Amber alert in their amber lettering, its grim message truncated in a style all too appropriate for the digital age: “BLK Female, 8 YRS, 4’0”, 70-80 LBS,” along with a contact number to report sightings. Radio stations had urged citizens repeatedly to be on the lookout.

Because I tend to leave WTOP news radio on a little too often when the children are around, my ten-year-old son grew preoccupied with the case, and because he cannot admit to himself that tragedy is ever actually happening, came to me and said, earnest with his watery blue eyes, “Mom, you know they found that girl.”

Hoping, hoping.

Spirit Connections

Some Western and global South churches have established “sister church” relationships as a more mutual alternative to the old mission field approach. Drawing on fieldwork and interviews, Janel Kragt Bakker studies the give and take of this model in Sister Churches: American Congregations and Their Partners Abroad. Oxford

Border Clashes

The documentary The State of Arizona captures multiple perspectives on undocumented immigration in the aftermath of Arizona’s controversial Senate Bill 1070, dubbed the “show me your papers” law. Directed by Catherine Tambini and Carlos Sandoval, it will premiere on PBS’s Independent Lens series on January 14 (check local listings). communitycinema.org

WHEN MY DAUGHTER, Jessica, was 7 years old, some of her best friends had American Girl dolls, so of course she desperately needed one as well. We asked three or four family members to chip in—these were expensive dolls—and got her one for Christmas.

Her doll, “Addy,” came with a story, as did each in the American Girl line. Addy and her mother had escaped from slavery in the American South, and they “followed the drinking gourd” north to Philadelphia, where they were eventually reunited with the rest of Addy’s family. It was a gripping story, especially for a 7-year-old. And the fact that Addy was about my daughter’s age made it all the easier for her to connect.

“It wasn’t so much that I learned ‘facts’” about slavery and race from the Addy stories, Jessica, now 27, told me recently, “but they made it all more personal. Addy was young, like me—I could relate to it.”

Other women who grew up with the dolls echoed that sense of connection with the various American Girl stories. Janelle Tupper, campaigns assistant at Sojourners, was around 7 when she received the “Kirsten” doll, a Swedish immigrant to the U.S. “My most distinct memory from the stories was that, on the boat, her best friend dies of cholera,” Tupper said. “Reading that passage was pretty devastating to me as a kid.” Other books in the American Girl series addressed issues of the day, from child labor to women’s suffrage. And while Tupper said she wasn’t aware as a child of the social justice themes in the stories—“I was just imagining life in the different time periods through the eyes of a character I identified with”—she now sees the series as addressing “societal change in terms that an 8- year-old can understand, often told through the characters’ friendships and family stories.”

You wait a long time for Christmas morning

drifting asleep even as the ebony slate of sky

shatters in clarion silence

Glory, Hallelujah!

and shepherds in the hills cast down their rods

look up at angels and find themselves

no longer huddled in darkness

but lucent between the stars.

It had been more than a week since the doctors had moved me into the ICU, and more than a week since I had tasted anything liquid.

My tongue was dry and felt like leather. At night, I would watch the machines around me blink. The IV bags hung next my bed and scattered the light across sterile white walls.

I tried not to cry when I could no longer control my bowels. I lay there in my own filth waiting for a nurse to rescue me.

I tried not to cry when I could no longer control my bowels. I lay there in my own filth waiting for a nurse to rescue me.

I came into the world unable even to clean myself and now it seemed I would leave it in the same state.

Finally the nurse arrived to help me.

“I’m thirsty,” I told her. “May I have an ice cube?”

She said no.

“Please? My mouth is so dry. Just an ice cube,” I begged.

“No.”

Oxygen tubes inserted into my nostrils had rubbed my nose raw. I pulled them out.

I felt relief. I watched the numbers drop on the LCD screen. An alarm sounded.

I tried to put the tubes back when the nurse ran in.

“Mr. King, you need the oxygen,” she chided, skillfully replacing al the tubes and checking all the machines and medicines that flanked my hospital bed — all the things that were keeping me alive.

Our son, Mattias, is eight years old. Everyone thinks their kid is special, and in a lot of ways, he’s just a regular kid. He loves fart jokes, enjoys riding his scooter and is obsessed with video games. But we’ve known he was different from a very early age.

Mattias started reading almost as soon as he began to talk. By age four, he could name any musical pitch or chord structure by name that he heard. He memorized his books after only hearing them a couple of times.

He also struggled to make friends, still has frequent bathroom accidents four years later, and he has meltdowns when things don’t go his way that would rival Bobby Knight’s chair-throwing basketball tirades.

But now, he’s finally starting to realize he’s different.