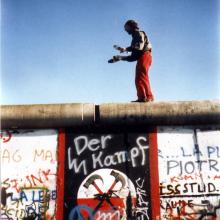

berlin wall

The wall wasn’t supposed to come down.

Günter Schabowski, a spokesperson for the East German Politburo, was tired. He hadn’t thoroughly read the travel regulation updates, handed to him shortly before his news conference. He didn’t know the document’s shifts in rhetoric, developed by leaders in the East German government, were simply an attempt to appease the swelling ranks of East Germans demanding reform. On Nov. 9, 1989, facing journalists’ cameras and notepads, Schabowski took questions for a forgettable almost-hour. Then someone asked about rumors the border may open.

Schabowski mumbled over his answer, confused. But a few of his words were clear: “Immediately ... right away.”

Reporters pounced. Breathless reports in West German media soon filtered over the wall through East Germans’ pirated signals. The Politburo had assured checkpoint guards that no changes had been made, but it was too late—a trickle of curious East Berliners quickly grew to massive crowds, yelling “Open the gate!” At a loss, and unable to get through to leadership for clarification or backup, the guards eventually gave in. Within hours, nearly 40 years of iron-fisted East-West divide was undone.

While Americans watch Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump fighting to the finish, in a noisy and polarized campaign, Germans are quietly debating their own presidential election in far different terms.

Among the names put forward as candidates are two leading Protestant bishops — one of them a woman — and even a respected Muslim writer.

1989 was a big year for me, and for the wider world. It was the year I left my teenage years behind. It was also the year that the brutality of government repression in Tiananmen Square rocked the world, U2 came to my home town and rocked the tennis stadium for seven nights straight, and my football team went back-to-back.

But the biggest news by far that year happened in November when the Berlin Wall came tumbling down literally overnight. For 28 years the wall had separated Berliners from each other, dividing not just a nation but whole systems of government — as well as families, traumatizing them in the process.

This is all very personal for me; I have German parents who grew up during a world war that saw their country devastated both from within and without.

Today marks the 25th anniversary of that most wonderful night when people who had been divided for decades were suddenly reunited, and thousands danced on the symbolic grave of separation, celebrating the death of division. For millions of Germans, it is no doubt one of the enduring memories of their lives. For them, Nov. 9, 1989 will never be forgotten.

I can still recall watching it on TV at my mother’s home. As I was watching, I looked over at Mum and saw tears streaming down her face, unable to believe the enormity of what was happening before her eyes. Talking to my dad later, he said he thought it would never happen in his lifetime.

Just over fifty-three years ago, a huge wall was built, a mighty fortress – a wall around East Berlin, a wall to keep out and a wall to keep in. This wall isolated people and forcefully molded them into a single, straight, dreary one-dimensional way of living. The wall represented an oppressive system without cracks, without breaks, without life.

Almost 500 years ago, a monk by the name of Martin Luther felt the pressures of another oppressive system, one in which a person was never sure of God or God’s mercy, one in which a person could even pay to climb the stairway to heaven quicker and easier. In many aspects, the church itself had become a fortress, dictating who was in and who was out.

Every system, every culture, every community risks succumbing to the temptation of shutting borders and protecting an identity. We are quickly seduced into the illusion of absolute control and power. Brick by brick, wall by wall, suspicion by suspicion, power is built, oppression takes hold. We construct an identity, a security, a world. We construct our own way to heaven. (Or is it to a ghetto?)

Who or what can defeat and break the walls, the towers, the fortresses we construct? Who or what can overcome oppression in the land? Where do we turn when creation shakes and societies are in an uproar?

Shakespeare said a rose by any other name would smell as sweet. Maybe, but a Stink Rose by any other name (say... garlic?) might get more play.

On July 19, Campus Crusade for Christ announced its plan to officially change its name to Cru in early 2012.

Brown v. Board of Education had not yet been fought in the Supreme Court when Bill and Vonetta Bright christened their evangelical campus-based ministry Campus Crusade for Christ in 1951. The evangelical church context was overwhelmingly white, middle class, and suburban. The nation and the church had not yet been pressed to look its racist past and present in the face. The world had not yet been rocked by the international fall of colonialism, the rise of the Civil Rights movement, the disillusionment of the Vietnam War, the burnt bras of the women's liberation movement, the fall of the Berlin Wall, or the rise of the Black middle class (more African Americans now live in the suburbs than in inner cities). In short, theirs was not the world we live in today. So, the name Campus Crusade for Christ smelled sweet. Over the past 20 years, though, it has become a Stink Rose ... warding off many who might otherwise have come near.