Apocalypse

I GREW UP heavily steeped in ’90s Christian rapture culture. I’d polished off all 40 books of the Left Behind kids series before I finished 6th grade, and holes formed in the knees of my favorite butterfly jeans because I wore them as often as I could to make sure I was raptured in them.

While the rapture is no longer central to my faith, I never realized how much apocalyptic thinking is soaked into our culture — and how much of it I absorb — until I picked up Dorian Lynskey’s latest book.

In Everything Must Go, Lynskey chronicles humanity’s unending preoccupation with the end, detailing how apocalyptic thinking has pervaded the media and pop culture throughout history, “turn[ing] fear into entertainment.” His book focuses on examples of apocalyptic thinking that “reveal something important ... about the times in which they were created.” Most obviously, apocalyptic imaginings reveal what we’re afraid of. Each era has had a different disaster to fear, be it nuclear, ecological, or cosmological. For millennia, the world has been ending again and again. “There is simply no end of ends,” Lynskey writes.

And some of the most influential end-time tales come from the Bible. From Genesis to Revelation, scripture is full of disaster narratives. “It is the Bible that supplies the primordial tales that surface over and over again in the art, literature, cinema, and television of the West,” Lynskey writes. “The Christian apocalypse is still with us, then, in a range of disguises.”

The U.S. has always considered itself as this New Jerusalem — a land specially blessed by God — but also one that is only available to those specially chosen. And from the establishment of the United States as a nation, as Lin discusses, this drive to only welcome certain individuals has been heavily focused on questions of race and national origin. The notion that the U.S. is a nation that welcomes immigrants is a myth that contradicts historical record. Instead, our “[i]mmigration and naturalization laws serve ultimately to create the ideal population as conceived by those who set policy and legislate,” Lin writes.

Beyond the Scandal

The Secrets of Hillsong draws on the reporting that exposed misconduct at the Hillsong megachurch. The docuseries goes beyond the headline scandals to explore patterns of abuse engrained in Hillsong’s history and asks what rebuilding looks like in the aftermath of scandal.

Hulu

HBO’S BIGGEST POST-APOCALYPTIC SHOW, The Last of Us, imagines a brutal world — and the mushroom zombies are only occasionally the source of danger. The first season followed Joel (Pedro Pascal), as he escorted teen Ellie (Bella Ramsey), who is immune to the zombie infection, to a hospital that can turn her immunity into a cure. In the final episode [SPOILERS], Joel and Ellie reach their destination. But when Joel learns they can only manufacture the cure by killing Ellie, he kills the doctor who was set to operate on Ellie. Joel’s decision raises the question: If the world can only be saved by sacrificing the innocent, is it a world we want to save? The Last of Us, itself an adaptation of a beloved video game, is far from the first show that employs apocalypse to interrogate our morality. Our end-time imaginings can show us who we are ... and who we could be.

The Greek title of the last book in the New Testament canon is Apokalypsis (“apocalypse”), the best English rendering of which is “revelation.” Revelation isn’t about the end of the world. It’s about a revelation — an unveiling. Revelation is one example from the genre of books we call apocalyptic literature. The genre, popular among Jews and Christians for hundreds of years before and after Jesus’ life, usually features a human receiving a message from some sort of divine messenger. The messenger wants to show the listener some deeper truth about the world — something that helps the audience participate more faithfully in the new world God is bringing forth.

The Last of Us has some of the characters you’d expect in an end-of-the-world series, including Bill, a survivalist portrayed with comical stoicism by Nick Offerman. Only one word can describe the look on Bill’s face when he emerges from his stately New England home, lowers his pistol, and pulls off his gas mask: relief. Not relief that his neighbors were still there, saved from the disaster that government officials had been warning them about, but quite the opposite: Bill’s relief comes from the fact that his neighbors have gone, evacuated to a quarantine zone while he hid in his heavily fortified safe room. With the entire town to himself, Bill indulges in his new life and gets what most doomsday preppers only dream of: an actual doomsday.

REVELATION IS AN intimidating book of the Bible to understand, let alone apply to everyday life. Dense with symbolic imagery and metaphors, it has been subject to innumerable interpretations and far-flung theories. But what are we to make of startling moments in the text, like when Jesus regurgitates a sword or John eats a scroll? In Upside-Down Apocalypse: Grounding Revelation in the Gospel of Peace, author Jeremy Duncan walks readers through Revelation by drawing parallels between the genres and figures of speech of John’s day and ours, lending clarity to how John’s apocalypse is deeply steeped in Jewish literary tradition and Roman culture. When we ignore this context, we miss the point of the final book of the New Testament: Revelation is not the wrathful reckoning of a conquering king; rather, as Duncan writes, it’s a testament to “how the Prince of Peace turns violence on its head once and for all.”

With each chapter, Duncan decenters “chrono-centric” approaches to Revelation, encouraging readers to avoid reading the text as “a story about me and my world and my time exclusively.” As the perfect, timeless witness of God, Jesus must be the guiding principle by which we understand all of scripture. Only then can we appreciate how God’s kingdom in Revelation contrasts with earthly kingdoms fueled by oppression. “[E]very time you awaken to how empire is trying to steal your imagination and make you believe in violence,” Duncan writes, “you have rightly interpreted Revelation regardless of the time period in which you awake.” Revelation asks us to watch for injustice, wherever and whenever it appears.

For those who have lost loved ones due to COVID-19, racist violence, or gun violence, Jesus’ apocalyptic hope that “the world as such” comes to an end is, perhaps, relatable. Here in the United States, we are expected to numb ourselves to the death-for-profit economy that’s been established; we are expected to go on with business as usual, never once pausing to cry out in judgment, “Woe to the world.”

THESE SCRIPTURES move with us from Christmas to Epiphany, drawing us into the mysteries of the divine life in the world. The incarnation is a call to notice where the Spirit surprises us with God’s presence. Dominican theologian Herbert McCabe guides our vision: “Christ is, indeed, to be found in the present but precisely as what is rejected by the present world,” he writes. Christ “is to be found in those who unmask the present world, those in whom the meaninglessness and inhumanity and contradictions of our society are exposed.” God’s mysteries are revealed among the rejected and despised, the people who expose society’s promises as the hypocrisies of political brokers who ensure the prosperity of the millionaires and billionaires—and, soon, the world’s first trillionaire.

To believe these scriptures about God’s presence is to realign our solidarities, to become conspirators with the One whose justice is liberation from the economic, political, and social patterns that are destroying life. These structures that organize our world for the benefit of the powerful are in the midst of collapse. They are “passing away,” as Paul claims. We’re always living through human self-destruction, with the United States as an instance of history’s cycles of cataclysm. If we want to go on in hope, then we must love those God has created, and give ourselves to the despised and rejected, to our neighbors caged in prisons and segregated from us by the border. There, God will astonish us with epiphanies: life’s survival on the underside of history.

JOHN LEWIS died the week I read this book. No American alive in 2020 was a better witness to the courage of nonviolent civil disobedience than Lewis. Ironically, that same week “warriors” from the federal government descended, uninvited and unidentified, on Portland, Ore. Violence exploded. The Bible’s final book, Revelation, seems more relevant than ever.

Thomas B. Slater’s slim volume is not a typical commentary on the biblical book, analyzing all its chapters and decoding all its symbols. Instead, Slater focuses on the political situation of seven small house churches in Roman-dominated Asia Minor (now western Turkey), to whom John of Ephesus wrote (Revelation 2-3). These believers lived in cities where temples or shrines represented the imperial cult, and all subjects were expected to offer sacrifices to the current “divine” emperor.

Who can forget Harold Camping, the Christian radio media mogul who picked two dates in 2011, hit the airwaves, put up billboards, solicited money — and nada. He joined some rather famous names — Edgar Cayce, Sun Myung Moon, Jerry Falwell, and Pat Robertson [at least twice, but before he had access to the White House], and John Hagee among them — of failed futurists. Heck, Sir Isaac Newton himself, great astronomer and mathematician, bet that Jesus would return in the year 2000.

As members of the left, we find ourselves wanting meaning, now, no less than did those who voted to Make America Great Again. We want a theodicy. We want answers. We want, in a sense, a religious explanation for how to proceed next.

It would be intellectually satisfying to come up with new narratives. It would also be lazy.

As Christians, what we are called to do is sacrifice that. We go on living. That’s it. We donate, if we choose to; we participate, when we can, in acts of goodness and solidarity and defiance; we rage against racism when we see it; when men grope women on subway platforms we follow the women to comfort them, as happened to me earlier this week. We do dull, good things, and we vote. We love, but do not soothe ourselves with the softness of that love. We deconstruct our own narratives, especially when they make us feel good.

We cry out in the wilderness. But we do not expect answers — not yet, and maybe not ever. If we are called to anything, now, it is do the work of living without them.

Like most interpreters, I believe that apocalyptic thought shaped Jesus’ vision. When he announced the kingdom of God, he meant it (Luke 4:43; 8:1). Jesus understood his ministry as God’s dramatic intervention into human history, a decisive moment that forced people to accept or reject what God was about. Yes, his ministry was meant to bring peace. But in an apocalyptic perspective, peace ultimately follows a period of intense conflict.

The world is falling apart.

Admittedly, the world has always been falling apart—since Christ’s resurrection, we’ve been living in the last age, and the New Testament is full of an apocalyptic expectation—but in our modern world, we seem to be spinning apart even faster. In our pop culture, either “winter is coming” or zombies are. Robots who look just like us are threatening genocide or a perverse “Capitol” is forcing our kids to kill each other. How to Survive the Apocalypse, by Alissa Wilkinson and Rob Joustra, looks at this theme in modern culture and what it might tell us about ourselves.

This is a book written by college professors, and I mean that in the best possible way. They define their terms, keep us engaged, and push us toward engaging the world like the best professors do. And, like all good professors, they are honest about their ideological approach: They are strongly neo-reformed and use Charles Taylor’s opus A Secular Age to interpret the culture that they address.

Indeed, How to Survive the Apocalypse is basically a fleshing out of Taylor’s description of the modern age (and its difference from a pre-modern era) through fictional ends of the world. Wilkinson and Joustra examine individualism and autonomy, a quest for and skepticism of authenticity, and the appropriate source of power (the questions and obsessions that Taylor sees at the root of modernity) through a half-dozen TV and movie apocalypses and dystopias, ranging from The Hunger Games to Her. These questions press all the more in our age, in which we seem to have lost the transcendent.

If this is your first Advent, or if it has been awhile, let me catch you up. Advent is the season of expectant waiting before Christmas. It’s a time to wake up, slow down, sit still, listen, and wait. A kind of expected, engaged waiting, with one another. And the first Sunday of Advent — celebrated on the four Sundays before Christmas — always starts with apocalyptic end-of-world scenarios.

Again, an odd way to start. But I think there is wisdom in it. The ancients saw fit to remind us of the harried, violent world into which the Christ child was born. Which, if we are honest, is also like the world in which we find ourselves.

Violence, brokenness, and heartache can take many forms. Each of us experience the heartache of recent weeks. Maybe it was a year-long affair; or Paris; or a lost job; or mass gun violence; or depression; or Laquan McDonald in Chicago, Ill.; or Garret Swasey in Colorado Springs, Colo.

Editor’s Note: ‘Left Behind’ starring Nicolas Cage hits theaters nationwide on Friday, Oct. 3. The film is based on the wildly popular book series and movies of the same title, in which God raptures believers and leaves unbelievers behind to learn follow Jesus and defeat the Antichrist. So how’s the film reboot?

Sojourners Web editors called up a group of religion writers in D.C. to watch and review the movie together. We left with more questions than answers. Here’s our takeaway on all things ‘Left Behind’ — and a little Nic Cage.

Catherine Woodiwiss, Associate Web Editor, Sojourners: So first things first — why Left Behind again?

When the books were published [starting in 1995], there was a debate happening in Christianity over whether Hell was a real, physical place. And the original movies were produced in the context of 9/11 and the Iraq war. So you can look and say, okay, this was a time of questioning what some saw as fundamental beliefs, of war and terrorism. So the popularity of an end-times series makes some sense.

But why now? Why today?

Editor's Note: Spoilers ahead! You've been warned.

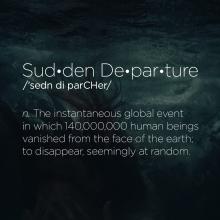

Over the past eight episodes of The Leftovers, HBO’s latest drama based on Tom Perrotta’s play of the same name, viewers have been treated to a case study in grief and faith in the midst of a life-changing event. Unlike the Left Behind series, which incorporated Christian triumphalism with terrible theology, The Leftovers examines the deeper human and spiritual issues of what would happen were two percent of the population to suddenly disappear. It is powerful and beautiful and really hard to watch (especially Episode Five). It asks the question: does life go on when your world is changed forever?

The show offers a variety of responses to the Sudden Departure of October 14: Kevin Garvey, the police chief who seems to be losing his mind after his wife leaves him for a cult and after his father needs to be committed; Nora Durst, who’s lost her entire family, so she keeps everything exactly as it was when the Sudden Departure occurred; Rev. Matt Jamison, Nora’s brother whose faith has been shaken because he was not taken; the town dogs who have become feral; and finally, the creepiest citizens of Mapleton, the Guilty Remnant, or the GR as they’re “affectionately” known.

This past week’s episode gave us a greater understanding of the GR. Although the nihilistic views of the Guilty Remnant are quite different from those of Christianity, I was struck by their powerful and strategic mission of witness. The cult was formed out of the recognition that everything changed on October 14 and that to pretend otherwise was foolish. The group, in their white clothes, their silence, their stripped-down existence, bears witness to the fact that they are living reminders of what happened. They are fundamentalists about their cause and willing to die for it — even if that death comes from their own hands.

EVERY SUMMER brings the end of the world. But not since 1998’s Deep Impact and Armageddon both threatened the end of the world with objects from space has there been such apocalypse redundancy in summer blockbusters: This year, class wars, real wars, ecological exhaustion, aliens, and zombie viruses destroyed our planet in as many different ways.

In her excellent e-book The Zombies are Coming!, Kelly J. Baker reminds us that apocalyptic fantasies have been part of the popular American imagination since at least the Puritan hellfire sermon. Even without a common religious narrative to guide them, end-of-the-world stories mostly function as a form of cultural critique and utopian longing. We can only imagine a desired future out of the ashes of the utterly destroyed present. In other words, things are going to have to get a lot worse before they get better.

If Baker is right that we seize on apocalyptic fantasies both to express a deep feeling that something is very wrong with our current state of affairs and to imagine some better alternative, then this summer’s world-ending movies display a profound lack of imagination. Most of them are not even particularly good at conceiving the end of the world, and none of them offer us a vision of how things might be different.

After Earth, for example, is more an overblown coming-of-age story than an apocalyptic thriller. The film follows Kitai (Jaden Smith) as he is guided via walkie-talkie by his wounded father (Will Smith) across an unknown planet. The planet turns out to be Earth 1,000 years after humans have high-tailed it to outer space. But since we never learn why humans had to leave, the apocalyptic frame feels like little more than an excuse to raise the stakes of Kitai’s journey and a chance to show off some fantastic technology. Kitai’s array of super-cool gadgets pretty much guarantees the creatures he meets will have to be more menacing than anything the old Earth could manufacture. The few glimpses we get of humanity’s new planet suggest a post-racial melting pot where everyone speaks a little Chinese and a lot of English and has a preference for flowing linen garments and nautical decoration schemes. I suppose this is a vision of a better tomorrow, but it felt more like a futuristic Pier One ad.

Expressions like "the world is getting worse and worse" and "we are living during the end times" are commonly thrown around within evangelical circles, and it needs to stop.

Are things really getting worse? Sure, church attendance might be down, fewer people are identifying themselves as 'Christian' on surveys, and the percentage of atheists continues to rise, but that doesn't mean the apocalypse is right around the corner.

Yet, I continually hear pastors and Christian leaders lament these evil times and Depraved Generation. They emotionally and emphatically condemn this fallen world and seemingly fulfill their own false prophecies by promoting a pessimistic outlook of the future of Christianity — simultaneously validating their theories by judging our future of Christianity: the youth.

The common scapegoat for Christianity's current “demise” is often blamed on young people, who are stereotyped as being more liberal, progressive, post-modern, and susceptible to spiritual relativism than ever before. They're the ones who have bought into the lies of the Emergent church, the temptation of the Prosperity Gospel, the sinfulness of our media-saturated world, and have become addicted to entertainment and denied the inerrancy of Scripture.

First things first: with all due respect to interim host John Oliver, I for one am thrilled to have Jon Stewart back on The Daily Show. I know it is sad to say, but I actually missed him while he was on summer hiatus. Welcome back, little buddy!

Last night, Stewart interviewed Richard Dawkins, author of The God Delusion, who was promoting his newest title, An Appetite for Wonder. The most interesting moments in the interview revolved around Stewart’s question to Dawkins about whether science or religion ultimately would be responsible for hastening our journey down this path of apparent self-annihilation. What followed was a fascinating, if not entirely satisfying, dialogue about the “downsides” of both disciplines.