This extravagant love poured out on my behalf felt like an offer of grace from God, a reminder that though the man I had dated couldn’t love me as I should be loved, God would make up for the rest. It was a convicting moment — I have often viewed this type of love and friendship as a consolation prize for not having a significant other. What a small way to live and love when you only expect love from spouse and children and see the love of friends and family as lesser. How could such a small group of people really show all the wonder and magnitude of God’s unfailing love toward us?

About 80 percent of Nepalese are Hindu, making Nepal the second-largest Hindu nation outside of India, with about 2 percent of the global total. Most Hindus believe in a kind of fatalism, and many here seemed unrattled by the quake as a test of faith, even as their temples and shrines were flattened.

“God had predestined it. He knew about it,” said Suresh Shrestha, a Hindu and a hotel owner. His house was partially damaged and he is living in a tent on the Tundikhel ground in Kathmandu.

Akriti Mahajan, a young girl who was standing outside her family’s tent nearby, suspects that man-made climate change had something to do with it.

“Humans are behind it,” she said. “If God had a role, this wouldn’t have happened.”

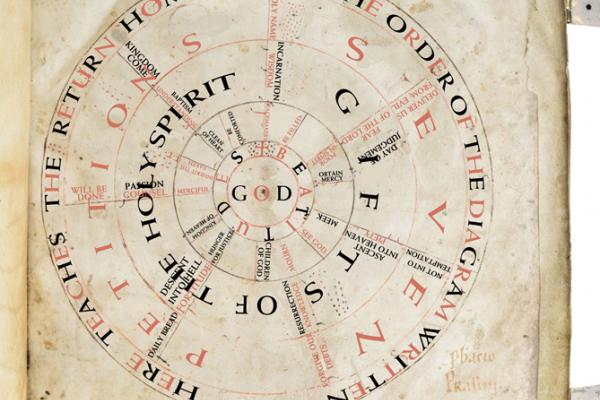

If much of life in the High Middle Ages seems foreign to us, the detailed workings of the wheel — along with four others like it that have survived to the present — are a real riddle.

Schematic prayer guides were more common in later centuries, said Lauren Mancia, a medievalist at Brooklyn College who has examined the Liesborn Wheel.

“Monks and nuns in the Central Middle Ages often get a bad rap for unsystematic thinking — doing all this prayer by rote, mumbling, and not caring about the sense,” said Mancia.

“This diagram suggests that they’re not just mumbling, they’re using a mnemonic device to remember and internalize, or even to make an inner journey.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., a self-identified socialist who’s perhaps the most left-leaning member of Congress, is expected to announce this week that he will seek the Democratic nomination for president. Sanders, 74, was born to Jewish parents and identifies as Jewish — though culturally, not religiously. Most political observers call him a super long shot for the nomination, but he will appeal to Democratic voters who admire his constant exhortations against the growing gap between the haves and the have-nots.

In a world of highly charged political rhetoric, the essay provides language and a framework for a community discussion on environmental ethics that takes a step back from immediate policy debate. This work doesn’t diminish the importance of these other discussions; rather it provides a context in which that work might be more readily possible.

Our ability to make meaningful collective moral decision requires us to be able to first have enough common moral language to have a conversation. This might be a good place to start.

Ultimately, Jesus shows us that our wounds do more than mark us — they connect us. Jesus knows that through the touching of his wounds, Thomas will be forever connected to him, doubts and all. Jesus knows that we must let our scars speak. In this beautiful, intimate encounter with Thomas, Jesus teaches us to let our wounds show and be touched so we too can know peace. Peace cannot come to us until we have the courage to proudly bare our scars and connect with one another through our wounds. Until then, we, like Thomas, will be left standing in our doubts and anxieties.

I will not pretend to fully understand the complex circumstances surrounding the death of Freddie Gray and the riots in Baltimore. But I have to wonder what would happen if we followed Jesus’ instructions to Thomas. What if instead of ignoring bystanders’ cries for Freddie Gray to receive medical treatment, the police had reached out their hands and held an inhaler for Freddie Gray? What if all the people of Baltimore had put their hands on Freddie Gray’s injured spine? What if the police force in Baltimore had reached out for the wounds of grief deeply gnawing within the rioting crowds? What if the crowds had placed their hands into the wounds of the injured police officers?

Hundreds gathered at Gallery Place Metro in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday night in solidarity with Baltimore activists to protest the death of Freddie Gray. The crowd marched for two hours across the city until reaching their final destination at the White House.

Leaders from multiple activist groups were helping lead the crowd, including Eugene Puryear, a candidate for the At-Large seat in the D.C. Council. The crowd began the march with chants of, "All night, all day, we're going to fight for Freddie Gray!" More solidarity events have been planned by the event organizers in the upcoming days.

Perhaps we are here again because we do not really listen. We gaze at each other’s pain and lament, but we don’t really see in a way that will shift our vision, clarify our perspective. We hear each other’s stories but don’t really listen in a way that will change us in a profound way, lead us to question our deepest held assumptions. We post a hashtag but don’t embody these digital signatures in our everyday lives?

Randy Berry, 50, is the U.S. special envoy for the human rights of lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and transgender people, the first such post ever created by a nation, according to the State Department.

In that trailblazing role, he said, he has an opportunity to help his two children grow up in a world more accepting than the one he was born into.

As someone who has “walked the personal journey of coming out,” Berry said, he knows how crucial positive messages and support are to a U.S. and global LGBT community plagued by young suicides.

Kenyan law bans homosexuality, and many clergy regularly preach against it as sin before God. But the ruling means that LGBT Kenyans will have an official platform from which to fight for their rights and freedoms.

“This is what we have been crying for,” said the Rev. Michael Kimindu, a former Anglican priest and now president of Other Sheep-Africa, a gay rights organization.

“It is the beginning of the journey towards freedom. We will now start asking: What happens when two people who are gay want to have a baby or want to go to church to marry?”