Nearly every home has at least one Bible, although few read it.

But 16 percent of Americans log on to Twitter every day. And that’s where author Jana Riess takes the word of God. A popular Mormon blogger at Religion News Service and author of “Flunking Sainthood,” Riess spent four years tweeting every book of the Old and New Testaments with pith and wit.

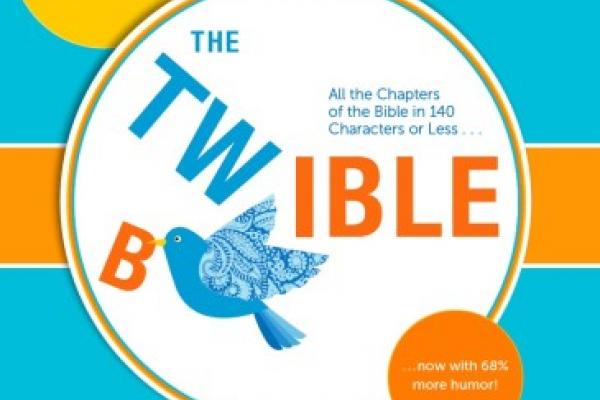

Now, the complete collection — each chapter condensed to 140 characters — is on sale as “The Twible,” (rhymes with Bible) with added cartoons and zippy summaries for each biblical book.

Her tweets mix theology with pop-culture inside jokes on sources as varied as ”Pride and Prejudice,” “The Lord of the Rings,” and digital acronyms such as LYAS (love you as a sister). To save on precious character count, God is simply “G.”

An organization of nonbelievers is threatening legal action against public schools that participate in an evangelical Christian charity that delivers Christmas toys to poor children.

The American Humanist Association, a national advocacy organization with 20,000 members nationwide, sent letters this week to two public elementary schools after parents complained their children were being asked to collect toys and money for Operation Christmas Child.

Operation Christmas Child is a project of Samaritan’s Purse, an evangelical relief organization founded by Franklin Graham, son of evangelist Billy Graham. Its stated mission is “to follow the example of Christ by helping those in need and proclaiming the hope of the Gospel.”

The toys collected by Operation Christmas Child come with an invitation for recipients to accept Christianity. Since its founding in 1993, Operation Christmas Child has sent 100 million boxes of toys to poor children.

It’s been 35 years since 918 people, including 257 children, died on Nov. 18, 1978, at the Peoples Temple massacre in Jonestown. The mass murder inside the South American jungle commune in Guyana was engineered by Jim Jones, a murderous cult leader, and was the only time in American history a member of Congress, Leo Ryan, D-Calif., was killed in the line of official duty.

Most of the victims were forced to commit suicide by drinking a fatal cocktail of poisoned punch spiked with a Valium tranquilizer. In the days that followed the slaughter of the innocents, Jonestown became a widely reported global event whose media coverage rivaled that of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

As a result of the massacre, “drinking the Kool-Aid” entered the popular lexicon to describe blind acceptance of a belief without critical analysis. Some of the Jonestown dead were not suicides; they were killed against their will, and the actual drink of death was, in fact, something called Flavor Aid.

When Pope Benedict XVI retired in February, I wrote an article in appreciation for his papacy. While he served as a great model of humility in stepping down from his role as Pope, what I appreciated more about Pope Benedict was his first encyclical, turned into a book called God is Love . In it, Benedict wrote these profound words:

Love is possible, and we are able to practice it because we are created in the image of God. To experience love and in this way to cause the light of God to enter into the world — this is the invitation I would like to extend with the present encyclical. (93)

God is Love is a powerful written reminder of the essence of Christianity. I hope more Christians of all stripes will read it.

Indeed, I appreciate Benedict for writing those beautiful words, but I love Pope Francis because he’s publicly living those words.

After serving as vice president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops for the past three years, there was little surprise when Archbishop Joseph Kurtz of Louisville, Ky., was elected this week to the top post in the American hierarchy.

Yet the nearly 250 churchmen would have been hard-pressed to find a better president to help them pivot toward the new, more pastoral path set out in recent months by Pope Francis.

Kurtz has earned his stripes with the hierarchy’s conservative wing thanks to his past work heading their campaign against gay marriage, but he was also molded by his early years as a pastor and his work in social justice — experiences he mentioned early and often when facing reporters after his election on Tuesday.

Speaker of the House John Boehner signaled Wednesday that there would be no immigration reform this year, an announcement made the same day that some of the nation’s most prominent evangelical pastors met with President Barack Obama to try to advance the issue.

Only months ago, immigration reform seemed to enjoy strong bipartisan momentum.

It still does across the nation, said Russell D. Moore, president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, one of the eight clergy invited to the Oval Office meeting.

“I urged the president not to make this a divisive issue, but to work with House Republicans,” said Moore. “We need to work together to fix the system rather than just scream at each other.”

The Obama administration, in a statement issued after the meeting, squarely blamed House Republicans for the impasse. The Democratic-led Senate passed a bipartisan immigration reform plan in June.

It's started.

I was following the Twitter feed for the conversation between Nadia Bolz-Weber and Amy Butler at Calvary Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. (#nadiaandamy) about the present realities and possible futures of Christianity in the United States, and it happened. I was happily dividing my cognitive attentions between Twitter and the television when it happened.

There was a Christmas ad.