On the eve of 2014, why not plan your New Year’s resolutions around caring for God’s creation? Here are eight ideas for EcoResolutions.

I’ve been thinking about what it means to be chosen, and conversely how we choose to be chosen. I’ve also been thinking about life, death, choices, and what happens to us after our earthly body dies. Do we remember who we are here? Do we remember our friends, lovers, enemies, acquaintances? Do we remember events, important moments, unimportant moments, or forgotten moments? I believe we do. The problem is that all we know and have experienced about the Divine is limited by our own thoughts and words.

As the Boy Scouts of America gets ready to admit gay youth, one Missouri organization has already broken away, but not because it favors tradition.

Oak Scouts is designed to be a safe space for everyone, regardless of faith or sexual orientation.

It all started when Kerry Kasten began guiding children’s meetings at a nature preserve and nondenominational Shamanic Wiccan church in Boonville. The more Kasten met with the children, the more she realized the need for a new type of scout troop.

“I realized there are all these parents out there who were not wanting to go into the mainstream scouting program due to disagreements in faith and sexual orientation,” Kasten said. “They wanted to go somewhere they felt safe being gay or pagan or not mainstream and express how they felt.”

On Wednesday, the Boy Scouts of America will begin accepting openly gay youths, a historic change that has prompted some churches to drop their sponsorship of Scout units because of the new policy.

Kabul, Afghanistan, is “home” to hundreds of thousands of children who have no home. Many of them live in squalid refugee camps with families that have been displaced by violence and war. Bereft of any income in a city already burdened by high rates of unemployment, families struggle to survive without adequate shelter, clothing, food, or fuel. Winter is especially hard for refugee families. Survival sometimes means sending their children to work on the streets, as vendors, where they often become vulnerable to well-organized gangs that lure them into drug and other criminal rings.

Last year, the Afghan Peace Volunteers (APV), young Afghans who host me and other internationals when we visit Kabul, began a program to help street children enroll in schools. The volunteers befriend small groups of children, get to know the children’s families and circumstances, and then reach agreements with the families that if the children are allowed to attend school and reduce their working hours on the streets, the APVs will compensate the families, supplying them with oil and rice. Next, the APVs buy warm clothes for each child and invite them to attend regular classes at the APV home to learn the alphabet and math.

Yesterday, Abdulhai and Hakim met a young boy, Safar, age 13, who was working as a boot polisher on a street near the APV home. Abdulhai asked to shake Safar’s hand, but the child refused. Understandably, Safar may have feared Abdulhai. But when Abdulhai and Hakim told Safar there were foreigners at the APV office who were keen to help, he followed them into our yard.

The past few months have flown by in true whirlwind fashion (my co-worker Katie aptly describes the professional whirlwind here). And as the hours tick down to the end of 2013, I find myself facing a bit of a personal whirlwind, surrounded by boxes, bins and far more hangers of clothes than I’m happy to admit. I am thick in the middle of a move, in what I’m calling my boomerang return to D.C. and Sojourners, after a three-year hiatus in the great Northeast.

As I pack up all my belongings, it’s becoming clear that books dominate an absurd amount of bins and boxes — turns out I have a penchant for the printed word (if moving isn’t a compelling argument for a Kindle, I surely don’t know what is). Therefore, it feels appropriate and timely to reflect on which of these titles affected me most this past year. As the director of Major Gifts (and newest member of the team), I’ve been particularly consumed with thinking through resource distribution, stewardship, and the power of the purse, so it is with this lens that I share my top reads of 2013.

To orientate a variety of foreigners for residence in North America, L. Robert Kohls and his staff at the United States Information Agency constructed a groundbreaking article, “The Values Americans Live By.” Kohls felt that visitors to the U.S. needed to understand “common American values” that would allow them to integrate more fully into the predominant cultural currents. All together, “The Values American Live By” highlights numerous ideals that most (but not all) U.S. citizens possess, all for the purpose of awareness building and cross-cultural understanding.

Among the topics Kohls covered in his 1984 article was the importance of time, for people from the U.S. often conceive of time in ways far different from others around the world.

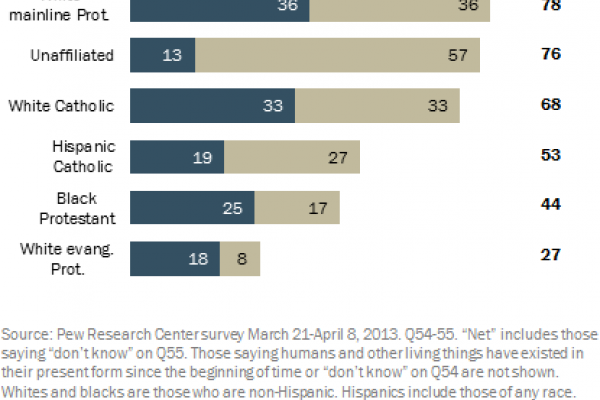

As evolution remains a contentious issue for many public schools, a new survey suggests that views on the question are driven by Americans’ religious affiliation more than their level of education.

Overall, six in 10 Americans say that humans have evolved over time, while one-third reject the idea of human evolution, according to a new analysis by the Pew Research Center. The one-third of Americans who reject human evolution has remained mostly unchanged since a 2009 Pew survey.

About one in four American adults say that “a supreme being guided the evolution of living things for the purpose of creating humans and other life in the form it exists today.”

While education matters, the new analysis suggests that religion appears to have more influence than level of education on evolution. The 21-point difference between college graduates and high school graduates who believe in evolution, for example, is less stark than the 49-point difference between mainline Protestants and evangelicals.