Pope Francis created his first batch of new cardinals on Saturday and used the ceremony to launch a new appeal for peace amid the violence racking so many countries.

Francis focused his remarks on the plight of Christians, but in an extemporaneous addition to his prepared text he also called on the church “to fight any discrimination” and “exclusion.”

“The church needs your compassion, especially at this time of pain and suffering for so many countries throughout the world,” Francis told the 18 new cardinals who were present in St. Peter’s Basilica, along with hundreds of other cardinals and bishops whose colorful vestments and diverse origins offered a grand tableau of global Catholicism.

Gay rights are colliding with religious rights in states like Arizona and Kansas as the national debate over gay marriage morphs into a fight over the dividing line between religious liberty and anti-gay discrimination.

More broadly, the fight mirrors the national debate on whether the religious rights of business owners also extend to their for-profit companies. Next month, the U.S. Supreme Court will decide whether companies like Hobby Lobby must provide contraceptive services that their owners consider immoral.

The Arizona bill, which is headed to Gov. Jan Brewer’s desk for her signature, would allow people who object to same-sex marriage to use their religious beliefs as a defense in a discrimination lawsuit.

There have been recent talks about increasing the federal minimum wage. However, there is a group of waged workers that is often overlooked in this debate: tipped workers. They are subject to the “tipped minimum wage” — $2.13 an hour. In fact, it has been 22 years since Congress raised the “tipped minimum wage.” According to federal laws, if a waitress or waiter makes more than $30 a month in tips, they can be subject to these wages. Out of the 50 states, 18 of these states pay servers $2.13 an hour, 22 of these states pay servers less than $3.00 an hour, and only seven pay them the federal minimum wage. Due to these unfair wages, it is estimated that servers are three times as likely to live in poverty.

Foreign law bans are back.

For the fourth year running, Florida is trying to outlaw the use of foreign and international law in state courts. Missouri has mounted another attempt to pass an anti-foreign law measure after last year’s effort was vetoed by Gov. Jay Nixon. The bans also have crept farther north, making a debut in Vermont.

These laws, which have passed in seven states, are the brainchild of anti-Muslim activists bent on spreading the illusory fear that Islamic laws and customs (also known as Shariah) are taking over American courts. This fringe movement shifted its focus to all foreign laws after a federal court struck down an Oklahoma ban explicitly targeting Shariah as discriminatory toward Muslims.

As Pope Francis led the world’s cardinals in talks aimed at shifting the church’s emphasis from following rules to preaching mercy, a senior American cardinal took to the pages of the Vatican newspaper on Friday to reassure conservatives that Francis remains opposed to abortion and gay marriage.

Cardinal Raymond Burke acknowledged that the pope has said the church “cannot insist only on issues related to abortion, gay marriage, and the use of contraceptive methods.” But in his toughly worded column in L’Osservatore Romano, the former archbishop of St. Louis blasted those “whose hearts are hardened against the truth” for trying to twist Francis’ words to their own ends.

Burke, an outspoken conservative who has headed the Vatican’s highest court since 2008, said Francis in fact strongly backs the church’s teaching on those topics. He said the pope is simply trying to find ways to convince people to hear the church’s message despite the “galloping de-Christianization in the West.”

The words “Christian” and “horror movie” rarely appear in the same sentence, much less in the same film’s promotional material.

Yet that’s exactly what Tim Chey, writer and director of “Final: The Rapture,” does to promote his picture in its city-by-city rollout.

As the movie’s poster promises: “When the Rapture strikes … all of hell will break loose.”

In an interview outside the Orlando, Fla., multiplex where his film is playing on a Sunday afternoon, Chey said he’s comfortable with the Christian horror movie label, or even “Christian disaster movie.”

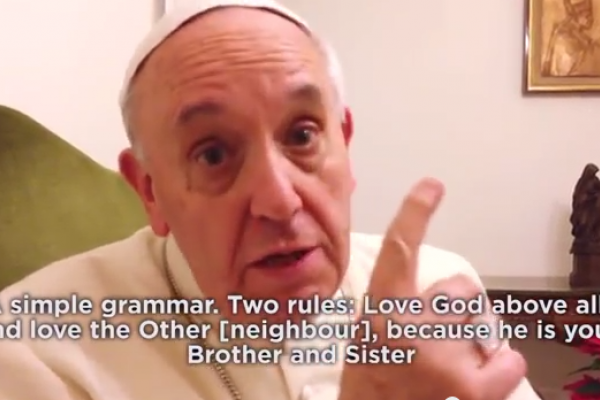

In an unusually informal video made on a smartphone held by a Pentecostal pastor, Pope Francis called on all Christians to set aside their differences, explaining his “longing” for Christian unity.

The seven-minute video, which was posted on YouTube, was made during a Jan. 14 meeting with Anthony Palmer, a bishop and international ecumenical officer with the independent Communion of Evangelical Episcopal Churches. Italian news reports say that the pope and Palmer knew each other when Francis served as the archbishop of Buenos Aires.

In his remarks, part of a 45-minute video, Francis said, in Italian, that all Christians are to blame for their divisions and that he prays to the Lord “that he will unite us all.”