BIBLICAL LAMENT includes both pleas to God for help and mournful dirges. Sometimes they are rooted in individual travails and grief, other times in anguish for those crushed by injustice or war.

The psalmist and the prophets dig deep into visceral images of bodily suffering—and stretch up, out, yearning to find symbols and metaphors in nature that might capture the mercy and presence of a God who, the psalmist isn’t afraid to say, is sometimes a bit elusive.

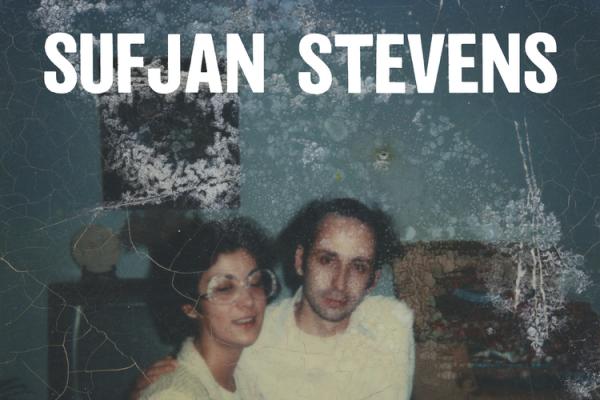

The album Carrie & Lowell is indie musician Sufjan Stevens’ multifaceted lament: For a mother, Carrie, he lost at least twice—to mental illness, addiction, and abandonment when he was a child and to cancer when he was a man. For the grief that surprised him after her death. For his inability, as he sings to his mother, to “save you from your sorrow,” hinting at that lingering, impossible guilt felt by so many children of troubled parents. Stevens reaches no tidy resolution in the course of the work (although early on, in the first song, he does offer that most basic, difficult, and saving grace: “I forgive you, mother”).

So why would you want to listen to something that speaks of so much pain? For starters, these are exquisitely spare, beautiful, and haunting folk-not-quite-rock songs. Stevens’ gift for hook and melody here is distilled, deceptively delicate, carried by few instruments and subtle effects. Layered vocals and harmonies swell up on a bridge or carry a song wordlessly to the end, like waiting choruses of angels, or ghosts.

Meanwhile Stevens’ lyrics move, like mourning itself, not in a straight line forward, but circling between memory, despair, longing, befuddlement, anger, regret, confession, and, at least occasionally, an acknowledgement of the “signs and wonders” that have him holding on to, or at least holding out for, God. These songs are psalm-like in their blunt details—suicidal thoughts, attempts to bury pain in sex and drugs, childhood neglect (“When I was three, three maybe four / She left us at that video store”), divine betrayal (“For my prayer has always been love / What did I do to deserve this now? / How did this happen?”), and the reminder, more than once, that “We’re all gonna die.”

These songs are also psalm-like in their hunger for a God who may be just out of the singer’s reach, but that he believes is there—glimpsed in the stars and ocean breakers, or in a young niece who seems to bear hope when everything else seems futile: “My brother had a daughter / The beauty that she brings, illumination.”

These are sad, sad songs. But they are some of the prettiest and truthful sad songs you’re likely to encounter this year. That artistic alchemy, of creating beauty out of pain, might speak, obliquely at least, to something sacred and redemptive, if you’re of a certain inclination. But to wrap this work of lament in a tidy redemption narrative is to hide its real power and strength: speaking honestly from the space between loss and longing; doubt and belief; the suffering that is and was, and the mercy that might yet be.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!