The definitive characteristic of Christian faith is that it is rooted in a historic event. We are the Resurrection People because the core of our belief, faith, ethics, and future hope lies in the 33 precious years of our God incarnated, culminating in him, the Suffering Servant, being nailed to that old rugged cross, and his subsequent rising from the dead.

The Christian faith has always been about God coming to save us in human form.

Everything we know about what it means to be a Christian is clothed with humanity. Jesus followers learn of what it means to be Christian by way of human relationships. We recite and affirm historical creeds passed down to us through the cloud of witnesses, the generations of believers before us. We are instructed in the moral values that align with Christian teaching by our mothers and fathers, whether biological or spiritual. Our local church community is our ethics classroom, a place where we practice, learn, and grow, working out our salvation and mobilizing the revolution of God in our particular corner of the world.

For being a television show based on absurdist humor and millennial first-world-problems, New Girl hit home earlier this month.

Winston, played by Lamorne Morris, is a roommate with a thousand changes in career, the latest and most lasting being that of a cop for the Los Angeles Police Department. The hilarity surrounding Winston has mostly been about his police training or his friend’s concern for his safety, when they tried to physically keep him from policing by stealing his cruiser keys. Then, with script writing help from Morris himself, New Girl took a momentarily serious turn.

When a pretty woman invites Winston on a date to the park for a rally to protest the police, who she describes arrested a 14-year-old because he “fit a description,” Winston declines, walking backward to hide his LAPD shirt.

He later says, “With everything that’s been going on, I just feel like she wouldn’t respect me.”

In that moment, Morris’ character finds himself caught between two conflicting worlds, what W.E.B. Du Bois called having a “double consciousness” — the brotherhood of a police force alongside white officers, keeping the peace and making neighborhoods safer; and the collective turmoil that comes with being a black man in a post-Ferguson America.

Many Americans must feel this conflicting pull and feel unable to voice it: citizens with friends or family who are officers and who are in solidarity with their black and brown neighbors; officers themselves who fear for their safety every moment they are on duty and battle with racial implicit bias because of harrowing experiences in their communities.

I myself feel this pull as a woman of color who grew up in North Philadelphia, where a mistrust of police was built into my framework of survival despite never once having a negative experience with Philly police. Solidarity with Eric Garner, John Crawford, and Dante Parker is a given. They are the kind of men I saw everyday growing up, men with questionable pasts and an unquestionable love for their families and communities — despite only the former being brought to light.

And I have met police officers working in neighborhoods where they and their partners are cornered and ambushed by street gangs; men and women with families, who are told they are hated by the black and brown children they rescue from crime scenes.

I turned to music as I wrote myself in circles, trying here to verbalize an emotion, a worried feeling that I’m not doing something right. I came across a radio interview with Community star and rapper Donald Glover in which he talks about what I believe Morris was battling with his New Girl script.

“Being young and black in America is schizophrenic. You kind of have to change who you are a little bit all the time for people to even respect you.”

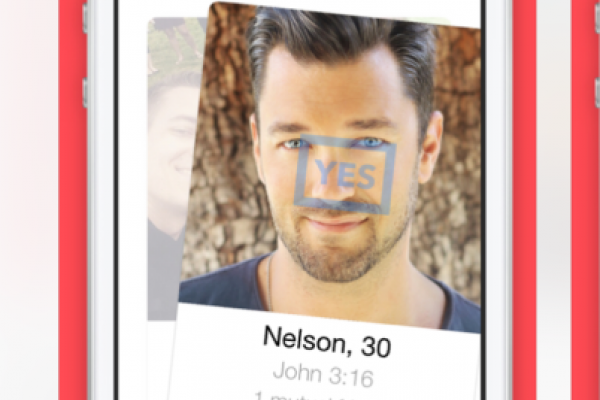

The first thing I had to do is enter my favorite Bible verse.

I debated for a while, thinking I could go the easy route and say it was John 3:16 or Philippians 4:13 (“I can do all things through Christ who gives me strength,”) but I was feeling cheeky so I entered Ecclesiastes 1:2 (“‘Meaningless! Meaningless!’ says the Teacher. ‘Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless.'”).

Then I entered my denomination — Protestant — and said that I’m looking for men. I allowed it to integrate with my Facebook account and I was in.

Welcome to Collide, a new app being billed as “Tinder for Christians.” It is one of many in the dubious tradition of (fill-in-the-blank) for Christians (Netflix, yoga , clothes), and as I went through the motions of joining, I wondered what good this was going to do, what perceived need it was filling.

The idea behind the wildly popular Tinder app is to go on dates with your match, of course, but it’s also to make split-second judgments based on your level of physical attraction to the person on the screen in front of you — and then maybe go have sex with them.

What I know of Christian culture — the kind of evangelical subculture that would spawn something like this, at least — would be pretty well set against the idea of a Christian Tinder.

Nearly a year removed from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Ordain Women founder Kate Kelly says she has found happiness living a more authentic life while continuing to push for equality in the Mormon faith.

Kelly, who was excommunicated in June 2014, now lives in Nairobi, Kenya, where she works on human rights efforts. She was back in the United States briefly on April 23 as part of an offshoot project of the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City to explain how she was punished for speaking out for women’s rights in the LDS faith.

“The men who (excommunicated me) literally think they kicked me out of heaven,” Kelly said.

“Luckily, I do not think that. … Out of this experience, I’ve realized that men don’t get to control my happiness. I’ve come out on the other end, (where) I think I’m much happier, much more authentic, a much more invigorated person.”

Still, on stage at the Gotham Comedy Club, a space usually filled by raucous laughter, Kelly broke down in tears talking about her ouster from the LDS faith and the repercussions for herself and her family.

“It’s like an execution, a spiritual death,” Kelly said of Mormon excommunication.

“It’s very, very extreme.”

For their part, Kelly’s Mormon leaders have said the door always is open to her return.

Caryn Riswold wrote a moving article about Bruce Jenner’s interview on Friday with Dianne Sawyer. In the interview, Bruce states, “For all intents and purposes, I’m a woman. People look at me differently. They see you as this macho male, but my heart and my soul and everything I do in life – it is part of me. That female side of me. That’s who I am.”

Caryn’s article is titled “How Should People of Faith Respond to Bruce Jenner?” It is a compassionate response to Jenner and all people who identify as transgender. She states that all people are created in the image of God and so deserve our love and compassion. Sadly, many religious people disagree with Caryn, insisting that Jenner is confused, crazy, or just out for attention.

Caryn worries that Jenner will be mocked and ridiculed. She states that people of faith should not respond with ridicule, but rather with acceptance and compassion.

Pay attention to the one who isn’t laughing. The one who looks upset. The one who is desperately trying to escape the gaze and the mockery.

Pay attention to the ones on the margins. Whose image are they created in?

The arrests of six Minnesota men accused earlier this month of attempting to join the Islamic State group highlights an unprecedented marketing effort being waged by the militant group in Iraq and Syria, U.S. law enforcement officials and terror analysts said.

It’s a campaign that is finding resonance from urban metros to the American heartland.

“This is not so much a recruitment effort as it is a global marketing campaign, beyond anything that al-Qaida has ever done,” said a senior law enforcement official.

The official, who is not authorized to comment publicly, said the Islamic State’s slick multimedia productions, its use of social media, and personal “peer-to-peer” communication are proving to be effective parts of a sophisticated program aimed at the West.

“I don’t think there has been one case in which we haven’t found some connection to the videos or other media the group has produced,” the official said.

Federal authorities have identified more than 150 U.S. residents who have sought to join the ranks of the terror organization or rival groups in Syria. There is evidence that about 40 of those have traveled to the region and returned to the U.S. Most have been charged; an undisclosed number are free and subjects of intense surveillance, the senior official said.

The smallest subset of the group, an estimated dozen, represents those who have actually joined the fighting ranks.

One hundred years ago — April 1915 — as World War I raged across Europe, the government of the Ottoman Empire attacked its Armenian citizens. Over the next several years, it is estimated that as many as 1.5 million Armenians died. Able-bodied men were murdered or enslaved as forced labor in the army, and hundreds of thousands of women, children, the infirm, and the elderly were marched into the Syrian desert to face death.

Supported by the Young Turks, an ultranationalist party that approved systematic deportation, abduction, torture, massacre, and the expropriation of Armenian wealth, the German-allied Ottoman government used the excuse of war to initiate the forcible removal of Armenians from Armenia and Anatolia where they had lived for centuries.

The targeting and mass murder of Armenians has been termed a genocide.

Although racial, ethnic, and religious wars have killed millions over the centuries, genocide is a unique byproduct of the 20th century. It requires both a rabid nationalism and the capacity of a central authority to organize and implement a sustained and systematic program of targeted mass destruction. Not until the 20th century had governments the necessary technologies, resources, and means to ally their historical ethnic, religious, or racist hatreds with radical nationalism to end the collective existence of a people.

The Armenian genocide was recognized and deplored around the world, even as modern Turkey resists the “genocide” label. American diplomats, Russians, Arabs, and German officers stationed in Ottoman lands witnessed the slaughter and alerted the wider world. In May 1915, Great Britain, France, and Russia vowed to hold the Turks personally responsible for their crimes. Relief efforts to save the “starving Armenians” were widespread.

Only a few dozen worshippers attend Boston’s Tremont Temple Baptist Church on a typical Sunday, but the historic church was once so prominent that legendary preacher Dwight L. Moody called it “America’s pulpit.”

This week, Tremont’s massive auditorium played host to influence once again when 1,300 Christian leaders gathered for the Q conference to discuss the most pressing issues facing their faith. There was no official theme, but one strand wove its way through multiple presentations and conversations: America’s — and many Christians’ — debate over sexuality.

While at least three other Christian conferences during the past year focused on same-sex debates, this is the only one to bring together both pro-gay speakers and those who oppose gay marriage and same-sex relationships.

“The aim of Q is to create space for learning and conversation, and we think the best way to do that is exposure,” said Q founder Gabe Lyons.

“These are conversations that most of America is having, and they are not going away.”

Which is not to say Lyons’ decision was without controversy.

Eric Teetsel, executive director of the Manhattan Declaration project that aims to rally resistance to same-sex marriage, urged Lyons to rescind his invitations to pro-gay panelists, whom he called false prophets professing to be Christians. Owen Strachan, president of the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, echoed the sentiment and tweeted that he was “shocked that @QIdeas features pro-‘gay-Christianity’ speakers.”

Lyons did not respond publicly to the criticism, but said such positions were rooted in fear.

In 2006, New Testament scholar David Trobisch abandoned such lofty outlets as Oxford Press and the Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy for a more mainstream venue: Free Inquiry.

In that feisty secular humanist journal, Trobisch identified the likely editor of the New Testament as second-century Bishop Polycarp of Smyrna and suggested that Polycarp, not Luke, wrote much of the book of Acts.

Trobisch shared the magazine’s cover billing with Christopher Hitchens and the atheist animal rights theorist Peter Singer.

None of this would be unusual — serious New Testament scholars constantly probe its cloudy origins, wherever that leads — if Trobisch were not now prominently employed by one of the most famously conservative Christian families in America.

The Green family of Oklahoma City — the plaintiffs in the U.S. Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby case — financed the 430,000-sqare-foot Museum of the Bible set to open in 2017 just off the National Mall in Washington.

It will showcase biblical artifacts from the 40,000-piece Green collection, one of the largest in private hands. As director of the collection, Trobisch does not run the museum (its director is Cary Summers), but in addition to enlarging, curating, and cataloging the trove, he participates in the crucial conversation about which items will go into the museum, and how.

One of the hot button topics in America today is same-sex marriage. This issue has been in the news often due to same-sex marriage bans being struck down in state after state and on the minds of many after the controversial “religious freedom” law passed in Indiana (and similar ones already enacted in other states). And it has been in the hearts of many gay and lesbian couples faced with the possibility of being denied access to services because of who they are and who they love.

Imagine planning and preparing for your wedding for months, making decisions about guest lists, music, menus, seating charts, and attire. You go to the lone bakeshop in town to talk about your cake choices, only to be told that the baker is not willing to work with you because you are gay or a bi-racial couple or a couple from another faith tradition. Imagine the feelings of rejection, isolation, and denial that you would potentially feel, because the state allows this denial of services. This scenario is not hard to imagine, because it is legally allowed in many places throughout our country.

“Othering” happens all the time for many different reasons – not just sexuality, race, and gender.

About 10 years ago, my son and I were at a local park playing on the swings when a group of young boys started taunting a small child with a disfigured arm about 50 yards away from us. They were calling her ugly names and throwing small rocks and sticks in her direction. We had seen this little girl playing happily, running around, and laughing with delight. But now she looked terrified.

I heard the taunts and began moving that direction to intercede, but my son outran me. Only six years old at the time, he yelled at the boys, “Leave her alone. She’s just like us.” The boys saw and heard my son and likely saw an adult close on his heels. They abandoned their harassment and ran away.