There has so far been no official accounting of what happened to Smith the morning of Nov. 1 on the second-floor landing of the Marbury Plaza Apartments in Southeast D.C. The Medical Examiner’s report tells part of the story, but there is still so much more unknown.

"I'm no longer stating that my son was beaten to death. My son was tortured to death. There are more injuries in the coroner’s report than I could visibly see with my eyes. There were injuries on my son’s back. He was hemorrhaging — the back. The back of his head was busted,” said mother Beverly Smith.

“Death has taken its toll. / Some pain knows no release / but the knowledge / of brave compassion / shines like a pool of peace.”

These words are engraved on the memorial pond at the Port Arthur mass shooting site in Australia. Nearby, a wooden cross is inscribed with the names of the 35 men, women, and children who died here. In contrast, a brochure at hand provides a simple explanation of what occurred in this place; it notably does not name the gunman. 1996: Australia’s last mass gun death.

Before the announcements of the new agreement at COP 21, when the thousands of people who were not closely engaging with official delegates of the 190 countries gathered in Paris, I was sitting at a small white table with my new found friend Kenneth.

We spoke for nearly an hour before I asked him the question.

We had been talking about the work of the Ghanian Religious Bodies Network On Climate Change, which brings together Muslims, Christians, and Indigenous peoples across Ghana to work on climate change because, after all, “climate change impacts all of us.” We touched upon capacity building, workshops, seminary education, practicalities, and visions. It was the kind of conversation that most people who were not directly involved in the negotiations were in Paris to have: networking, information sharing, and building cross-cultural relationships around common endeavors.

Finally, I asked him, “Are you religious?”

Of course Obamacare is failing.

Not quite as badly as No-Obamacare was failing, so I'm still glad it exists. It's a necessary stopgap until we find a system that actually works. But you know what? Single-payer healthcare will fail just as badly.

Yes, I know that single-payer healthcare systems succeed in other developed nations. I also know that competitive insurance-based healthcare systems succeed elsewhere. But neither system will succeed in the United States, because the U.S. is the only nation on earth that refuses to keep healthcare spending from spiraling out of control. If the cost remains the same, it doesn't matter who's paying. In the long run, we all are.

National Geographic magazine recently named Mary, the mother of Jesus, “the most powerful woman in the world” as an appraisal of her ongoing influence and popularity. But do Mary’s words and example have a prayer of being heard and effecting change in this time of war?

Indeed, this is war. America has effectively been engaged in continuous warfare since the weeks after September 11, 2001. In a few decades we’ll learn what happens when whole generations of people grow up and take charge of a society that has waged war their entire lives.

Attempts to tone down the descriptions we use for warfare or the way we conceptualize the present conflict don’t change anything. No end is in sight. Others turn up the rhetoric: after the San Bernardino shooting, at least one presidential candidate insisted the USA now finds itself in “the next world war.” Another one puffed up his chest and boasted of his resolve to “carpet bomb” people. We hear this stuff so often, we’ve become numb to its magnitude.

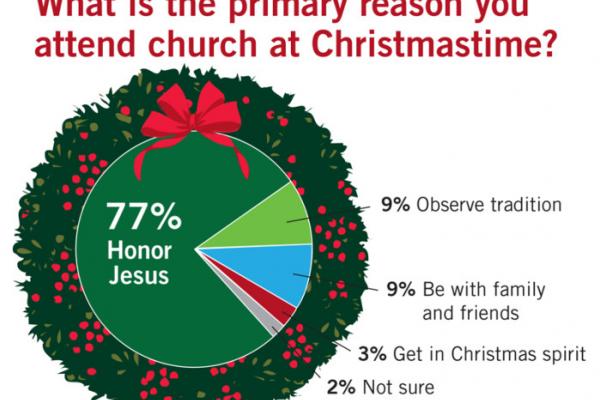

December means curtains up for church Christmas pageants, hand-bell concerts, caroling kiddie choirs, and Nativity displays on the front lawns.

But the No. 1 reason most U.S. adults — Christians and many unbelievers, too — give for going to church at Christmastime is to “honor Jesus,” according to a new survey from the evangelical research agency LifeWay Research.

More than three in four of churchgoers (77 percent), Protestants and Catholics alike, said they were drawn to attend church to honor the birth of their savior, the fundamental religious experience of Christmas above and beyond all the seasonal fa-la-la-la-la.

Pope Francis hailed the “historic” climate change agreement signed in Paris, urging the international community to swiftly implement the deal.

Speaking to the faithful in St. Peter’s Square on Dec. 13, Francis called on world leaders to act on the unprecedented environmental agreement signed on Dec. 12 by nearly 200 countries.

“The conference on climate has just finished in Paris with the adoption of an agreement, defined by many as historic. Carrying it out will require a unanimous commitment and generous dedication on everyone’s part,” he said.

After 9/11, Kathy Masaoka heard a Muslim woman on the radio describe her hesitancy to go to the market for fear of being attacked.

“It crystalized for me at that moment, that this must be how my parents felt and how my family felt after Pearl Harbor,” she said.

Masaoka’s family is Japanese American. As a young man during World War II, her father was drafted into the Military Intelligence Service while his parents and siblings were sent to California’s Manzanar internment camp in the desert east of the Sierra Nevada. They lost their family business in Los Angeles.

In this season of preparing for Christmas, there is a growing number of unaccompanied children arriving on the U.S. southwestern border. The numbers have been increasing in the last few months, enough to move government offices to prepare for their coming. National security continues to be the most important governmental concern, but even then, laws require that migrant children detained by our government be fed and sheltered until they can be released to a legal sponsor. It leads me to wonder: If governmental offices are preparing to receive these unaccompanied children, then what are we Christians doing to prepare to receive them?

Every Christmas as the story of the birth of Jesus our Lord is read in congregations and in homes there are always the laments about how sad and even cruel it was that there was no place for Mary and Joseph and the baby Jesus. Where was the loving and caring welcome for them? We cannot change the most unwelcome reception the Christ Child received at his birth, but we can learn from it.