Veteran Catholic writer Tom Roberts thought he knew Sister Joan Chittister — the maverick Benedictine nun who dares speak her mind to her church.

He didn’t.

When Roberts, editor at large for the National Catholic Reporter, went to interview her three years ago in Erie, Pa., at the community where she entered religious life at age 16, a secret she’s held for a lifetime came to light.

Kenya has welcomed the return of 700 citizens who had joined Somalia’s al-Shabab militant group that has attacked churches, malls, and government institutions, most notably Garissa University College where nearly 150 people — mostly Christian students — were killed last spring.

The return of the Kenya nationals was reported by the Kenyan government, the Supreme Council of Kenya Muslims, and the International Organization for Migration.

“They will undergo rehabilitation, before being re-integrated into the community,” said Hassan Ole Naado, deputy general of the Supreme Council of Kenya Muslims.

Catholic leaders made a rare appeal to the world’s politicians on Oct. 26, urging them to take strong action at the highly-anticipated U.N. climate change summit later this year.

Nine cardinals, patriarchs, and bishops representing the Catholic Church across five continents signed a document, presented at the Vatican on Oct. 26 by clergy from Belgium, Colombia, India, and Papua New Guinea.

The document presents a 10-point policy proposal calling for “a fair, legally binding, and truly transformational climate agreement.”

Tall, lanky, cheerful, and confident, Esmatullah easily engages his young students at the Street Kids School, a project of Kabul’s Afghan Peace Volunteers, an antiwar community with a focus on service to the poor. Esmatullah teaches child laborers to read. He feels particularly motivated to teach at the Street Kids School because, as he puts it, “I was once one of these children.”

Esmatullah began working to support his family when he was 9 years old. Now, at age 18, he is catching up on school.He has reached the tenth grade, takes pride in having learned English well enough to teach a course in a local academy, and knows that his family appreciates his dedicated, hard work.

When Esmatullah was nine, the Taliban came to his house looking for his older brother. Esmatullah’s father wouldn’t divulge information they wanted. The Taliban then tortured his father by beating his feet so severely that he has never walked since. Esmatullah’s dad, now 48, has never learned to read or write. There are no jobs for him.

Recognizing the incredible gap (between those with health insurance and those without it) in the health care system in their area, nurse practitioners Mary Wysochansky and Anna Stinchcum decided to do something to address the problem. These two women founded and opened the Sumter Faith Clinic in Americus, Ga. The clinic serves the uninsured and the underinsured in Sumter County, Ga. Funded purely by donations and staffed by volunteers, Sumter Faith Clinic provides healthcare for those in need that tends to the body, soul, and mind. Their desire to make justice happen was possible because these two women decided to join their efforts and work for a better future.

In 2014, the U.N. Women launched a campaign to revisit and reengage with the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action on gender equality. The slogan of the campaign is “Empowering Women, Empowering Humanity, Picture It!” The platform identified 12 areas for attention in working for the rights of women and girls: Poverty, Education, Health, Violence, Armed Conflicts, Economy, Power/Decision-Making, Institutional Mechanisms for Advancement, Human Rights, Media, the Environment, and the “Girl-child.” At the original 1995 Beijing conference, 189 countries committed to this platform for achieving gender equality and female empowerment. Beijing +20 (twenty years after the Beijing Declaration) reminds us that, while advancements in gender equality and the empowerment of women have been made, there is still much work to do.

The story of Job is one of the literary classics in the Bible. It is a story that tries to sort out why bad things happen to good people. It is a story that tries to make sense out of suffering. It is a story that concludes with an epic confrontation between Job and God. And it is a story that captures the isolation, the misunderstanding, and the feelings of abandonment.

Job’s friends and his wife are convinced that it is Job’s sin that has led to his misfortunes. That has a familiar ring to people trapped in violent and abusive relationships. “Why did you make him mad?” friends ask. “Why don’t you just leave?”

And inside the relationship, the abuser often threatens even greater harm if the victim tells anyone about what is happening. And if the victim decides to leave, the risk of violence increases, often with lethal consequences.

As Job said of God, “If I go forward, he is not there; or backward, I cannot perceive him; on the left he hides, and I cannot behold him; I turn to the right, but I cannot see him…If only I could vanish in darkness and thick darkness would cover my face!” (Job 23:8-9, 17)

Victims of domestic violence – both women and men as well as children – often feel isolated, abandoned by family and friends who are uncomfortable or afraid of the topic, trapped by religious traditions that stress male dominance and the indissolubility of marriage and feel forgotten by God. Job knew that feeling.

Today (Oct. 26) marks the fourteenth anniversary of the passage of the Patriot Act, an initiative designed to strengthen the U.S. government’s ability to monitor and deter potential terrorist threats.

Though key provisions of the Patriot Act expired earlier this year, many of them were restored by the Senate via passage of the USA Freedom Act, and will be effective through 2019. At the same time, the Senate also voted overwhelmingly to end the NSA’s unmonitored mass surveillance and data collection of phone and email records, formerly justified under the language of the Patriot Act.

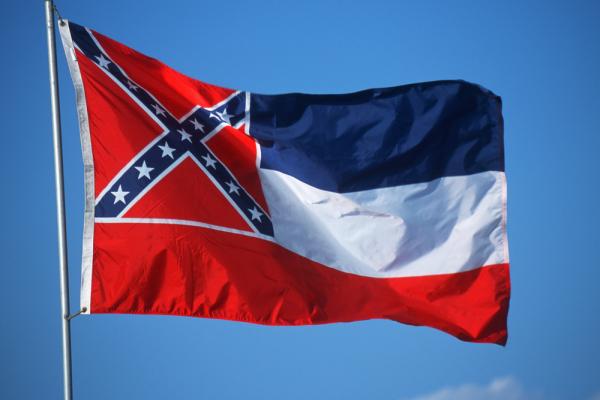

Campus police officers at the University of Mississippi removed the state flag from its campus this morning, days after resolutions from the student body, staff, and faculty urged such action, according to a press release from the University of Mississippi.

It is the first predominantly white institution of higher education in the state of Mississippi to ban the flag.

The student senate was the first to pass the resolution, after 3 hours of "respectful and impassioned debate" culminating in a 33-15-1 vote in support of removal.

A majority of evangelical pastors consider Islam to be “spiritually evil,” according to one just-released poll, but on Oct. 23 an evangelical pastor and an imam took turns talking about their friendship and mutual respect.

Texas Pastor Bob Roberts and Virginia Imam Mohamed Magid joined dozens of other religious leaders in prayer at the Washington National Cathedral before signing a pledge to denounce religious bigotry and asking elected officials and presidential candidates to join them.

“I love Muslims as much as I love Christians,” said Pastor Bob Roberts, of Northwood Church in Keller, Texas, before leading a prayer at the “Beyond Tolerance” event.

“Jesus, when you get hold of us, there’s nobody we don’t love.”

The most significant and contested gathering of Roman Catholic bishops in the last 50 years formally ended on Oct. 25 after three weeks of debate and dispute, but the arguments over who “won” and who “lost” are only beginning.

The synod of 270 cardinals and bishops from around the world was the second in a year called by Pope Francis to address how and whether Catholicism could adapt its teachings to the changing realities of modern family life. Traditionalists had taken a hard line against any openings, especially after last October’s meeting seemed to point toward possible reforms.

While the delegates made hundreds of suggestions on a host of issues, two took center stage, in part because they represented a barometer for the whole question of change: Could the church be more welcoming to gays, and was there a way divorced and remarried Catholics could receive Communion without an annulment?