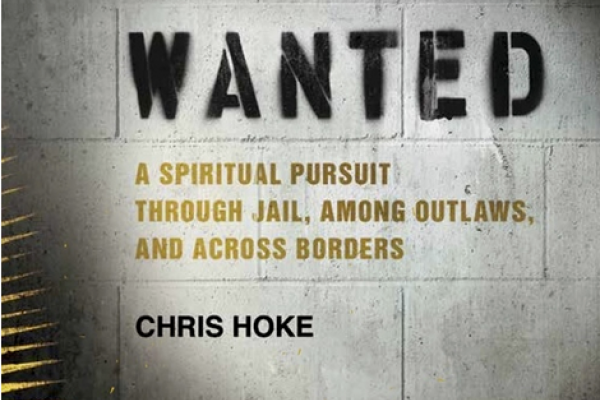

Wanted: A Spiritual Pursuit Through Jail, Among Outlaws, and Across Borders is non-fiction, but I read it like it was one of the latest blockbuster novels, this time with gorgeous writing. I couldn’t put it down, and I didn’t want the journey to end, following Chris Hoke through jails and streams and farms of Washington’s Skagit Valley as he grew from a young man interested in faith outside the walls of the church to a pastor to the “homies” of the area, as they called themselves—men whose criminal past or undocumented status have caused them to be among the most marginalized in our society. This book is imbued with dignity, prayer, and an understanding that relationships require forgiveness, on both sides. Wanted is a beautiful reflection on what the life of faith looks like in action.

Hoke grew up in southern California but was drawn to the dimmer corners of the Christian faith. He made his way to northwest Washington state to work with Tierra Nueva, a ministry that “seeks to share the good news of God’s freedom in Jesus Christ with people on the margins (immigrant, inmates, ex-offenders, the homeless).” We recently chatted about his work with Tierra Nueva, the value of a good metaphor, and how reading the Scriptures in prison can make them new.

Read the Full Article