Editor's Note: This post originally appeared on Good Letters: The Image Blog.

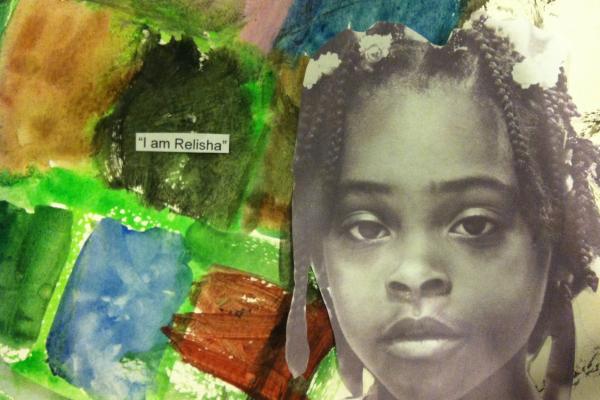

The first ominous sign that the Relisha Rudd case was slipping from the local Washington, D.C. imagination was when the police alert signs posted on the roads into the city had their messages changed, or were removed entirely.

For weeks after the news that the little eight-year-old girl was missing broke on March 19, the digital display boards had broadcast the Amber alert in their amber lettering, its grim message truncated in a style all too appropriate for the digital age: “BLK Female, 8 YRS, 4’0”, 70-80 LBS,” along with a contact number to report sightings. Radio stations had urged citizens repeatedly to be on the lookout.

Because I tend to leave WTOP news radio on a little too often when the children are around, my ten-year-old son grew preoccupied with the case, and because he cannot admit to himself that tragedy is ever actually happening, came to me and said, earnest with his watery blue eyes, “Mom, you know they found that girl.”

Hoping, hoping. All of us were hoping — although apparently some of us not quite enough, because it soon came out that Relisha had been missing from her home since February 28, and had not been seen at all after March 1. “Home,” in fact, was the massive city homeless shelter located at the former D.C. General Hospital complex on the backside of Capitol Hill — the location also of the city methadone clinic, as news reports inevitably mention — where Relisha lived with her mother and multiple siblings in cramped quarters.

There’s a depressing and familiar story of family breakdown here — you can go online yourself and read the pronouncements of judgment placed on the ineffective, troubled mother — but there were also extended family members, mentors, and coaches who endeavored to make up the difference in providing cleanliness and warmth and hugs.

But because a traumatized child, in particular, is like a shade flower ready to bloom at the promise of any sun provided, there was an opening for the attentions of a fifty-one-year-old man named Kahlil Tatum, a janitor at the shelter who started out as a kind of uncle figure for Relisha, taking her on outings and buying her presents, and who later assumed the persona of a “Dr. Tatum,” forging doctor’s notes to ensure that the numerous school absences were excused.

It was with Tatum that Relisha was last seen, via the silent witness of hazy, time-stamped security camera footage, walking side-by-side down the hallway of a Holiday Inn Express just miles from my house, and entering one of the rooms. It is the overwhelming contention of commenters online that Relisha’s mother must have been trafficking her daughter in exchange for money and presents, and to watch the short and captured loop of film is to sense that one has witnessed some kind of depressing and illicit transaction indeed.

That hotel hallway video, however, only came out later: After the school and the shelter finally got their arms around why Relisha was missing, Tatum had disappeared himself. He and his wife of twenty-odd years checked into a faded suburban motel where the next day, the wife was found shot dead, presumably at Tatum’s hands.

After Tatum had been recorded buying extra-large leaf bags at a home store and his cell phone tracked to the Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens park — an island of verdant green wetland at the heart of the city, and a mere mile or two from my house — the Metropolitan Police Department descended upon the park. What they found in an isolated storage shed, however, was not Relisha, but the body of Tatum, who had apparently (“had the good sense to,” I always find myself mentally adding) shot himself.

Now there is no apparent trail to Relisha, though the investigation continues. The MPD combed the park from end to end, later joined by neighborhood volunteers, but nothing was revealed. While most observers fear that she is dead, others in the online cadre believe she may have been sold into the commercial child sex trade.

Not two months after her disappearance, the attention around the case has started to ebb. At first the alert signs were gone, then the Washington Post ceased reporting on the case every day. I find myself praying for her, day and night, lying in my bed amid the vortex of urban thoroughfares that were some of the last places she was seen.

You might well wonder what the grounds for my emotional investment in this case, and Relisha, are. What can I, middle-aged housewife, surfeit with white privilege, someone who merely plays at living along the ragged urban edge, know or feel about these unexplainable circumstances? It is a question I cannot answer, beyond the demands of my faith that we are all responsible for one another’s children, that every soul, always, is irreplaceable and precious.

So I concentrate on Relisha Rudd instead, although I keep wondering why a media that reported on JonBenet Ramsey for more than half of my life moves so quickly to forget about Relisha’s. Nobody ever called that case a “local Denver story,” even though Relisha’s story gets so easily subsumed into a generalized hype about the District of Columbia and its much-vaunted failures.

And even though it contradicts everything I claim to believe about violence, I find myself wanting to believe that Relisha shot Tatum, turned on her feet and ran through Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens, and is holed up somewhere warm and safe. Or maybe she is running: endlessly alive and on the move, like the runaway girl Esmeralda in Don DeLillo’s Underworld whose movement keeps her from being dragged into the South Bronx’s undertow of drugs and violence. Or is she now merely an apparition?

Somewhere, whether dead or alive, Relisha has a body and soul. If she is alive, I pray for that body’s safeguarding, and if she is dead, I trust that her soul is with the blessed, for she has already faced her judgment.

A native of Yazoo City, Miss., Caroline Langston is a convert to the Eastern Orthodox Church. She is a widely published writer and essayist, a winner of the Pushcart Prize, and a commentator for "NPR’s All Things Considered." This post originally appeared at Good Letters HERE.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!