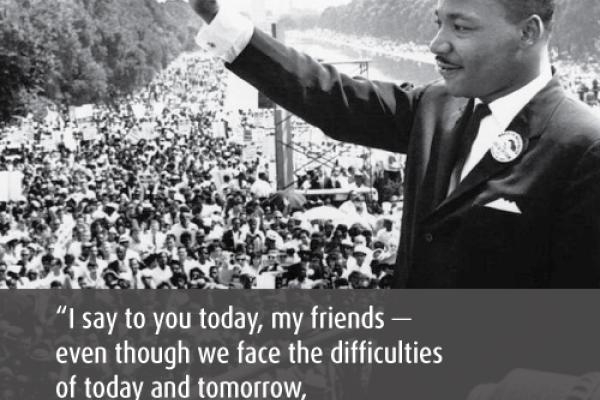

Yesterday was the 50th anniversary of a day that changed America, changed the world, and changed my life forever. I was fourteen years old on Aug. 28, 1963, in my very white neighborhood, school, church, and world. But I was watching. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., became a founding father of this nation on that day, so clearly articulating how this union could become more perfect.

He didn’t say, “I have a complaint.” Instead, he proclaimed (and a proclamation it was in the prophetic biblical tradition), “I have a dream.” There was much to complain about for black Americans, and there is much to complain about today for many in this nation. But King taught us that day our complaints or critiques, or even our dissent will never be the foundation of social movements that change the world — but dreams always will. Just saying what is wrong will never be enough to change the world. You have to lift up a vision of what is right.

The dream was more than the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, which both followed in the years after the history-changing 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It finally was about King’s vision for “the beloved community,” drawn right from the heart of his Christian faith and a spiritual foundation for the ancient idea of the common good, which we today need so deeply to restore.

Last night I was in Belfast, Northern Ireland, speaking about the beloved community and the common good to a church full of leaders seeking a way toward a new future after so many years of painful and violent history. In London, I spoke to the BBC about how King’s dream has been fulfilled and how it has yet to be. Over last weekend, I joined the Greenbelt Festival for faith, arts, and justice, which drew 25,000 people, many of them young, who want their faith and their lives to make a difference in changing the world.

I am here for a two-week book tour of God’s Side: What Religion Forgets and Politics Hasn’t Learned About Serving the Common Good. Next is Scotland, Manchester, and then back to London to speak to both church and political leaders about how “the common good” might help us find common ground by reaching higher ground. Here too, politics often blurs solutions to our most important problems — and as President Barack Obama reminded us yesterday at the Lincoln Memorial “that change does not come from Washington, but to Washington; that change has always been built on our willingness, We The People, to take on the mantle of citizenship — you are marching.” I am telling people in the U.K. that change is also true of London and every other capital of the world.

Change comes from the kind of social movements that descended on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. My latest book encapsulates how the common good begins with our personal decisions and how it then can reshape our culture, economy, and democracy, and eventually even our politics. Many of the quarter million people who marched on Washington 50 years ago and heard the dream had already learned that and went home to turn the dream into reality.

Our biggest issue is hope, and the deep hunger for it. As I travel, that has been a central theme — how hopelessness and cynicism are our greatest spiritual dangers. But hope is the most important thing the faith community has to give to the world and to social movements for change. And the 50th anniversary of the march and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s extraordinary “I Have a Dream” speech are such personal and powerful reminders of that for me.

I have been personally moved by the reminders of that providential moment in the final speech at the March, when King’s favorite gospel singer, Mahalia Jackson, told the preacher from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, “Martin, tell them about the dream!” King set aside his prepared remarks and did just that, reminding us all to put down our prepared notes and cautious plans and speak from the depths of our own souls and the soul of our faith to the soul of our nations.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!