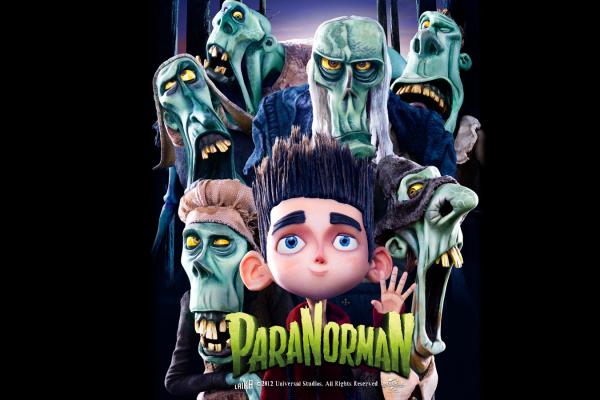

Paranorman, the stop-motion animated feature by Laika Studios just came out on Netflix instant download, so we decided to watch it for our family movie night. It's a fun film, perhaps a bit too scary for the little ones, but what really stood out for me was the surprisingly deep morality in this little film. This comes in an unlikely package since the film is about zombies and witches. Not surprisingly, if you look for Christian reviews of the film you will see many focus on warnings to stay way from the occult. Sadly, this response misses the profoundly deep moral message behind this film — one that confronts religious violence, and instead promotes a message of redemption and forgiveness. That's quite a bit of insight for a cartoon!

The premise of Paranorman is that the town of Blithe Hollow (not coincidentally set in Massachusetts, as we will see later) is about to be overrun by zombies because of the curse of an evil witch. Only Norman Babcock, an odd boy who can speak to the dead, can save the day. The movie begins by having us get to know Norman, who is emotionally isolated because his family does not understand him, and his peers ostracize and ridicule him as a "freak" at school. The only person who believes Norman is his friend Neil Downe, and overweight boy who is himself bullied.

The town is in peril because three centuries ago, an evil witch was executed, and in revenge put a curse on puritan judge and her accusers, cursing them to rise from the grave as zombies. So each year the curse of the witch must be appeased by reading from a mysterious book at the grave of the witch in order to prevent a zombie apocalypse. But this year that does not happen, and the zombies overrun the town. The townspeople and local police form the typical Frankenstein mob, complete with pitchforks and shotguns to kill the zombies. As the mob mentality grows, Norman and his motley band are threatened by the mob as well.

This is the first point where we see the film’s unmasking of "virtuous" violence: in the logic of many films, so long as someone is a "monster" or an "alien," it is okay to kill them. So we have no problem with watching mass killings of monsters or aliens in movies because ... well ... they're monsters. So you're supposed to kill them. That's what good guys do in movies. This is the unquestioned plot of hundreds of movies. As long as the Storm Troopers in Star Wars are faceless, we don't bat an eye when Luke kills one after the other. They have been dehumanized, and so it's okay to kill them all. The same is true for the Orks in Lord of the Rings, or the witch and her minions in the Chronicles of Narnia.

Read the Full Article